A distinguished bloodline: the medicinal leech

From antiquity to the NHS, leeches have been humans' healthcare helpers

The first televised boxing match, broadcast live from Harringay Arena in February 1939, saw 19-year-old Eric Boon beat Arthur Danahar to the title of British Lightweight Champion. The victorious Boon wasn’t unscathed, however – he left the ring with an eye injury and knuckles ‘swollen up like puff pastry’. Moorfields Eye Hospital sorted out his shiner by applying two leeches to the inflammation, leaving him fit enough to head to court to deal with a speeding summons. What an eventful couple of days!

Although some news reports expressed surprise that the ancient practice of leech therapy persisted in the 20th century, it had been there in the background all along. The leech has accompanied humankind for thousands of years, appearing in a medical context in Ancient Egyptian, Arabic and Ayurvedic works. The Sanskrit text Suśrutasaṃhitā (c. 300-500BC), for example, recommended bloodletting for cases of newly formed swellings, and recognised that the leech was the gentlest way to do this for delicate patients.

Within the Greco-Roman concept of the four humours – which held that an imbalance of blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm was responsible for disease – it made sense to remove superfluous blood. Although Hippocrates didn’t mention leech therapy, the practice lent itself well to humoralism and the idea of restoring the body’s equilibrium. Humoral theory remained at the forefront of Western medical approaches throughout the Middle Ages and did not become entirely obsolete until the acceptance of germ theory in the late 19th century.

A ‘singular little reptile’

Most 19th-century commentators on leech therapy did not, however, major on the humours. Removing blood was more about reducing inflammation and calming the pulse, and the heroic Hirudo medicinalis – the medicinal leech – was the one for the job. In contrast to bloodletting with a lancet, the leech completed the process gently and tidily, and could even be used as a home remedy when a surgeon was unavailable.

In 1798, London apothecary George Horn wrote a treatise on the nature and medical use of leeches, advising readers on how to look after them. His charming style of writing conveys his fondness for and appreciation of his slimy assistants:

‘This singular little reptile, which possesses so many remarkable properties, designed for the use of man, deserves our warmest gratitude to our Supreme Benefactor.’

He was also empathetic towards the creatures. Commenting on practitioners who used salt to force the leech to disgorge its contents (in order to make it ready for second breakfast) he said:

‘Those persons do not consider that blood is the most favourite and salutary nourishment of this extraordinary creature, and I would ask such inconsiderate persons how they would feel themselves, if, immediately after eating a hearty dinner, any person was to give them a violent emetic.’

How to apply a leech

Former naval surgeon Rees Price referred to leech therapy as sangui-suction in 1822, but the name does not seem to have caught on. He detailed the use of leeches for a variety of conditions – in dysentery for example, up to three dozen of the animals were to be placed on the abdomen, while those suffering chronic inflammation of the liver had to put up with eight to ten leeches ‘around the verge of the rectum’.

Price recommended that the area of skin was cleared of hair, washed with soap and water, and rinsed off. It could be moistened with milk, but he found porter the best thing for encouraging reluctant leeches to bite. He applied them in an upturned wineglass, but it was also possible to buy specialised glass tubes to focus the animal’s attention on the correct location. Another writer on leeches, John Rawlins Johnson, was not so keen on the wine glass method due to the leeches’ tendency to ‘retire to the upper part of the glass and remain at rest, defying all attempts to dislodge them.’ Both he and George Horn preferred to wrangle the leech into position by hand and place its mouth directly onto the patient’s skin. According to Price, however, ‘A healthy leech will soon become sick, from being held in a warm hand.’

A leech labour shortage

By Price’s time, leeches were already scarce in the United Kingdom on account of medical demand and loss of habitat, and the four principal London-based importers were bringing in around 7,200,000 a year from the continent. Supply chain issues would intensify over the next decade as the leech industry boomed, driven at least in part by the theories of French military surgeon François-Joseph-Victor Broussais (1772-1838).

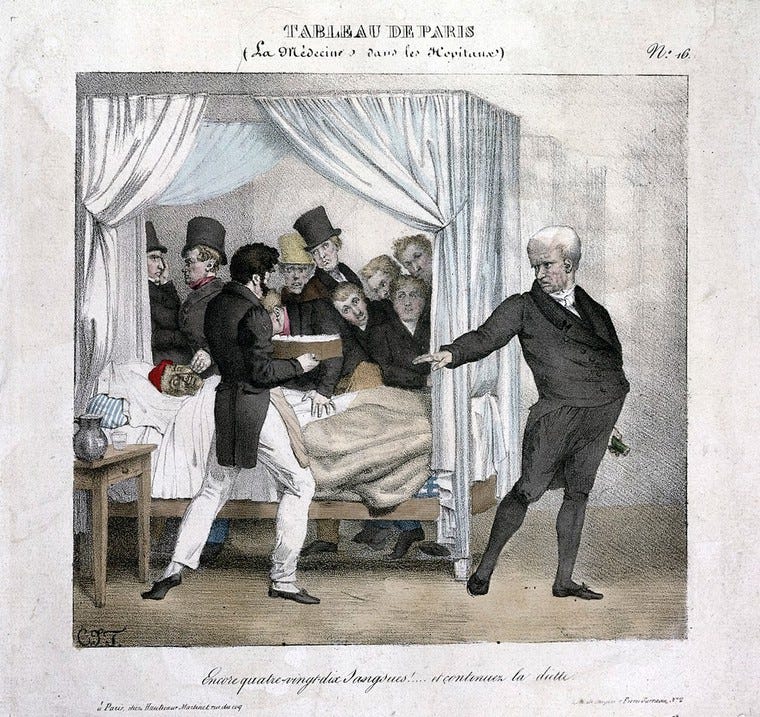

Broussais believed that every disease stemmed from inflammation and could therefore be brought under control by bloodletting. His patients at the Val-de-Grâce military hospital in Paris had no chance of avoiding leeches, regardless of what was wrong with them. The simple concept of one cause and one solution for all disease appealed to the public, and the leech had a fashionable moment that contributed to the decimation of Europe’s wild populations.

The early 19th-century writers understood that something about leeches prevented blood from clotting, but it was not until 1884 that Dr John Berry Haycraft tested this hypothesis and confirmed that ‘the leech secretes from its mouth a fluid which destroys the blood ferment without producing any other observable change in the blood.’ This would become known as hirudin, and is one of the compounds that gives leeches a role in medicine today.

Wartime scarcity

The Great War led to another shortage, Europe’s best leech-gathering regions being then occupied by ‘scenes of blood-letting by other and far more powerful agencies’. Dr A E Shipley of Christ’s College Cambridge wrote in 1914 that Hirudo medicinalis had become practically extinct in England – ‘although I know of a naturalist who can still find them in the New Forest, but he won’t tell anybody where.’ One newspaper also mysteriously claimed that ‘It is said that there are leeches in Croydon.’

Fortunately, with help from The London School of Tropical Medicine and the Indian Museum, Shipley arranged for a consignment of the species Limnatis granulosa to be shipped over from Kolkata. Despite being passengers on a P & O boat, they managed to arrive in a healthy state and, according to Shipley, were ‘willing and even anxious to do their duty.’

Even leech enthusiast Dr Shipley had to admit that most 20th-century doctors were not clamouring to recruit these critters to their practice team. When Eric Boon took the punch to his left eye in 1939, Moorfields Hospital pharmacy kept about 100 leeches on standby at a time – more than most hospitals but not on the scale of the millions feasting on Europe’s population a century earlier.

21st-century healers

The rationale for using leeches is no longer related to the four humours but to their anticoagulant powers. Leeches are used to avoid venous congestion in reconstructive surgery cases – for example, when a severed finger has been reattached or the delicate blood vessels of a skin graft need time to knit together. The hirudin and calin produced by the leech keep the blood flowing both during the bite and for hours afterwards. Around 600 NHS patients a year receive treatment from leeches bred at a hi-tech farm near Swansea.

Like the leeches themselves, some earlier writers’ comments about them remain relevant. Dr Shipley managed to sneak a little topical commentary into his studies when he remarked that the proportions of a leech were difficult to measure, for: ‘its body is as extensile as the conscience of a politician’.

Scroll down for sources.

Featured events

This week I’ve stuck to a few UK-based events, but will expand the geographical range and work out the best format for this section in future editions. If you have an event you would like included, let me know at thequackdoctor@substack.com.

London: The Wellcome Collection’s current exhibition, Milk, has a Relaxed Opening from 6.30pm on 2 Sept 2023. This calm and friendly event is designed to be accessible for neurodivergent visitors, and there will be sensory equipment and quiet spaces available.

Oxford: Uncomfortable Oxford’s history of medicine walking tour takes place on 3 and 24 September 2023 at 2pm (more dates available too). Oxford University students lead this fascinating walk, beginning at the Bridge of Sighs and lasting about 1 hr 45 mins.

Leeds: The Thackray Museum is offering free guided visits to the East Leeds War Hospital, which cared for injured soldiers during the First World War. Visits are at 1pm on 11, 13 and 15 September 2023 and booking is not required.

Glasgow: At the Hunterian Museum at 1pm on 22 September, book historian Dr Michelle Craig will be talking about her work recataloguing the library of the celebrated 18th-century obstetrician Dr William Hunter. This ‘Friday Focus’ talk is free to attend – reserve a spot online.