A fortune-teller’s love potion

Two sisters fell victim to a clairvoyant’s claim that a mysterious substance would help them find husbands

A shorter version of this article originally appeared on TheQuackDoctor.com. I’m intending to bring most of the stories about fraudsters over here and focus on the advertised medicines there - although there is inevitably some overlap!

As ever, thank you for reading - I really appreciate your interest and support.

A rag, worn close to the heart, and steeped in a mystic substance imbued with the wisdom of the East. A flame, charring the edges until smoke curls and billows and at last takes shape. What is it that forms in this cloud of shimmering grey? Behold! A man, handsome and kind (and rich); a perfect Valentine for Miss Dora Lyne.

The vision appeared in 1930, in the Yorkshire town of Bridlington. Miss Lyne and her sister Mabel visited Madame Burdett, a palmist who held booths at charity fêtes and told people what they wanted to hear. The sisters became friendly with her and sought a more specific prediction. Both wanted husbands, and Madame Burdett was to be their supernatural matchmaker.

‘Madame Burdett’ was the professional name of Ethel May Wilkinson (born c. 1874), who set up as a fortune-teller in Bridlington in 1925. Unlike most fortune-tellers, however, she did not just predict the future – she also claimed the ability to influence it.

Her power derived from a magical substance that she referred to as ‘Zep’. A Zep reading cost the astonishing sum of £25, but this was a bargain considering that when burnt in methylated spirits, Zep would reveal the face of the client’s future beloved. Not only that, but it would also ‘hold’ him so that he could not bestow his affections elsewhere.

Money with menaces

The Lyne sisters had reached their late forties without much luck in love, and were prepared to go to great lengths to change their situation. They were living on their own means, and apparently had money to burn. After the initial palm reading, Wilkinson upsold a more detailed consultation, allegedly telling Dora Lyne:

‘I think you have known a man for some time. There is a woman stands between you. He cares a great deal for you. The other woman seems to hold him. He is not a very happy man through this. I cannot get you together without help, and that would cost £25. But the affair is worth it.’

Both Dora and Mabel Lyne spent their entire savings on Zep readings in the first half of 1930, even selling £150-worth of jewellery to fund the habit. By the time Wilkinson was arrested in June 1932, Dora was living in receipt of out-relief and Mabel had been obliged to go into service. The actual charges against Wilkinson referred to sums of £75 and £50, but the evidence given in court suggested that they had lost more than £600 in total.

It was not, however, just their bank balances that came under threat. When no husband materialised, Dora Lyne asked for her money back, but Wilkinson allegedly frightened her into signing a document to say she had only paid £15. If Miss Lyne didn’t sign, Wilkinson would put Zep on her and she would be cursed forever. Miss Lyne claimed that Wilkinson had been physically violent to her and told her:

‘If you give me away, I will put a knife into you; not only the blade, but the haft as well.’

A dubious past

Ethel May Wilkinson had been in trouble before. Her husband Amos followed the ostensibly respectable profession of a veterinary surgeon, but while living near Newport Pagnell in Buckinghamshire in 1911, he and Ethel began receiving stolen goods from a man named Ernest Druce. Druce was an author who had studied at Pembroke College, Oxford; he had then published a comic novel called Ray Farley and a poetry book, Sonnets to a Lady. From this promising start, however, he appears to have turned into a bit of a spiv, who latched on to the Wilkinsons and even moved in with them for a while, paying his way with a selection of dodgy goods.

Druce had previously spent time in jail for ordering expensive cigars and not paying for them. A similar modus operandi characterised his dealings with the Wilkinsons. He would go to drapers’ and milliners’ shops, request items ‘on approval’ with promises to pay at a later date, and then never return. If the shopkeeper was uncertain about letting him take the goods, he would suggest they telephoned Mrs Wilkinson for a reference, which was inevitably glowing. By the time of their arrest in 1912, the Wilkinsons had moved to Nuneaton, but couldn’t outmanoeuvre justice.

Amos Wilkinson claimed in court that his wife and Druce had concocted the plan without his knowledge. This might well have been true, but the judge was unimpressed with his lack of chivalry, saying:

‘As for you Amos Wilkinson, I consider your conduct in attempting to throw the blame on your wife as mean and disgraceful to yourself as a husband and as a man.’

All three were sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment.

A sacred substance

But back to the events in Bridlington in 1930. Ethel Wilkinson challenged Dora Lyne to go out into the street, pick an unsuspecting chap she liked the look of and bring him back to the house, where he would be sprinkled with Zep to ‘stop him from bolting.’ Thankfully, Miss Lyne did not follow this instruction.

The origins of ‘Zep’ were an exotic mystery: according to Dora Lyne, Wilkinson said it was a sacred animal brought from the Far East to Germany and there made into a preparation that was conveyed to London and sold in tubes for £25 and £75. At the trial, however, Wilkinson’s daughter Winnie Hewer gave a different story – when in Florida in 1926, she had encountered a substance called ‘zoophite’ used in Native American charms. She sent some to her mother, who she knew was into that sort of thing. Wilkinson called the powder ‘Z’ for short, and this became ‘Zep’.

Whether animal, vegetable or mineral and whether it came from East or West, it clearly didn’t work. Dora and Mabel Lyne were now without husbands and without the comfortable finances that they had started with.

Wilkinson claimed Zep was so powerful that, when poured onto barristers, it would ensure they won their cases, but she did not put this into practice at her own trial – she was found guilty of false pretences and fraudulent conversion and sentenced to 18 months’ hard labour.

The story almost developed a romantic twist. Widespread reporting of the case prompted a naval petty officer to write to Dora Lyne expressing his interest in a relationship with her. She travelled to Portsmouth to meet him, but any romance was short-lived and he disappeared to Scotland, leaving her with unpaid bills and a still-unclaimed hand in marriage.

In 1934, Dora Lyne was arrested in Portsmouth for obtaining two pairs of shoes and two dresses from a tradesman by false pretences. She was of no fixed abode and the courts appear to have felt sorry for her, as they adjourned her case indefinitely and released her into the care of a Salvation Army officer.

Eventually, however, things started to look up. Dora took a job as housekeeper for an elderly Great War veteran in Fareham. In 1952, when she was 71, she married Charles E Westmore, a relative of her employer. Zep’s miraculous powers might not have been instant, but they got there in the end.

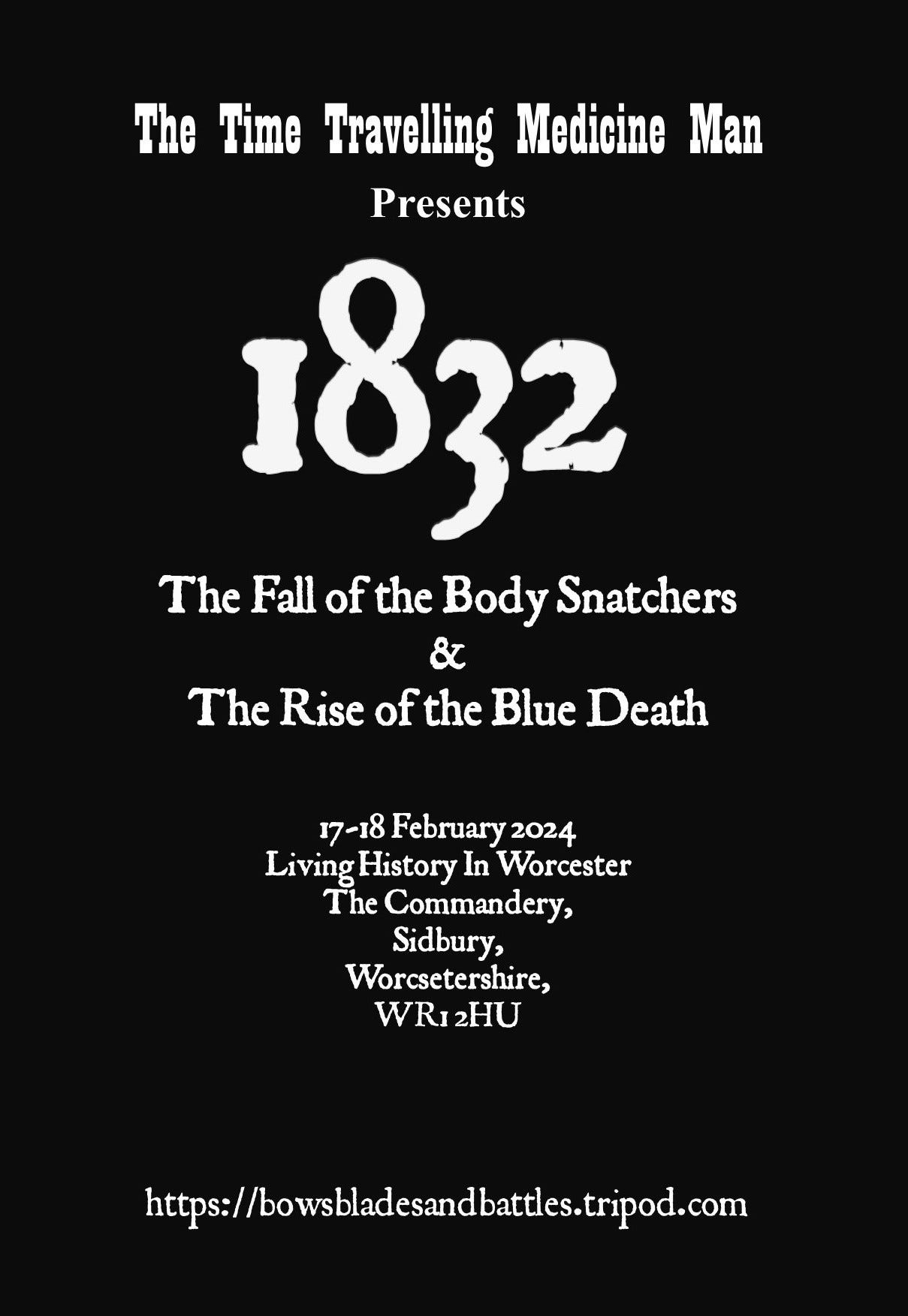

Living History in Worcester 17-18 February 2024

Worcester’s historic Commandery – famous for being the Royalist Headquarters during the Battle of Worcester in 1651 – is the venue for a lively weekend of historical reenactment on 17-18 February. There will military displays, traditional crafts, music and dance – but the highlight of your visit will surely be The Time Travelling Medicine Man, whose wealth of knowledge and fascinating examples of historical surgical instruments make him a hit with audiences of all ages!

The Time Travelling Medicine Man will take visitors back to the pivotal year of 1832, when the Anatomy Act put bodysnatchers out of a job and a new threat arrived on Britain’s shores in the form of the deadly cholera.

Admission £9 for adults, £4.10 children, free for under-5s. Book online or pay on the day.

From The Quack Doctor Archives

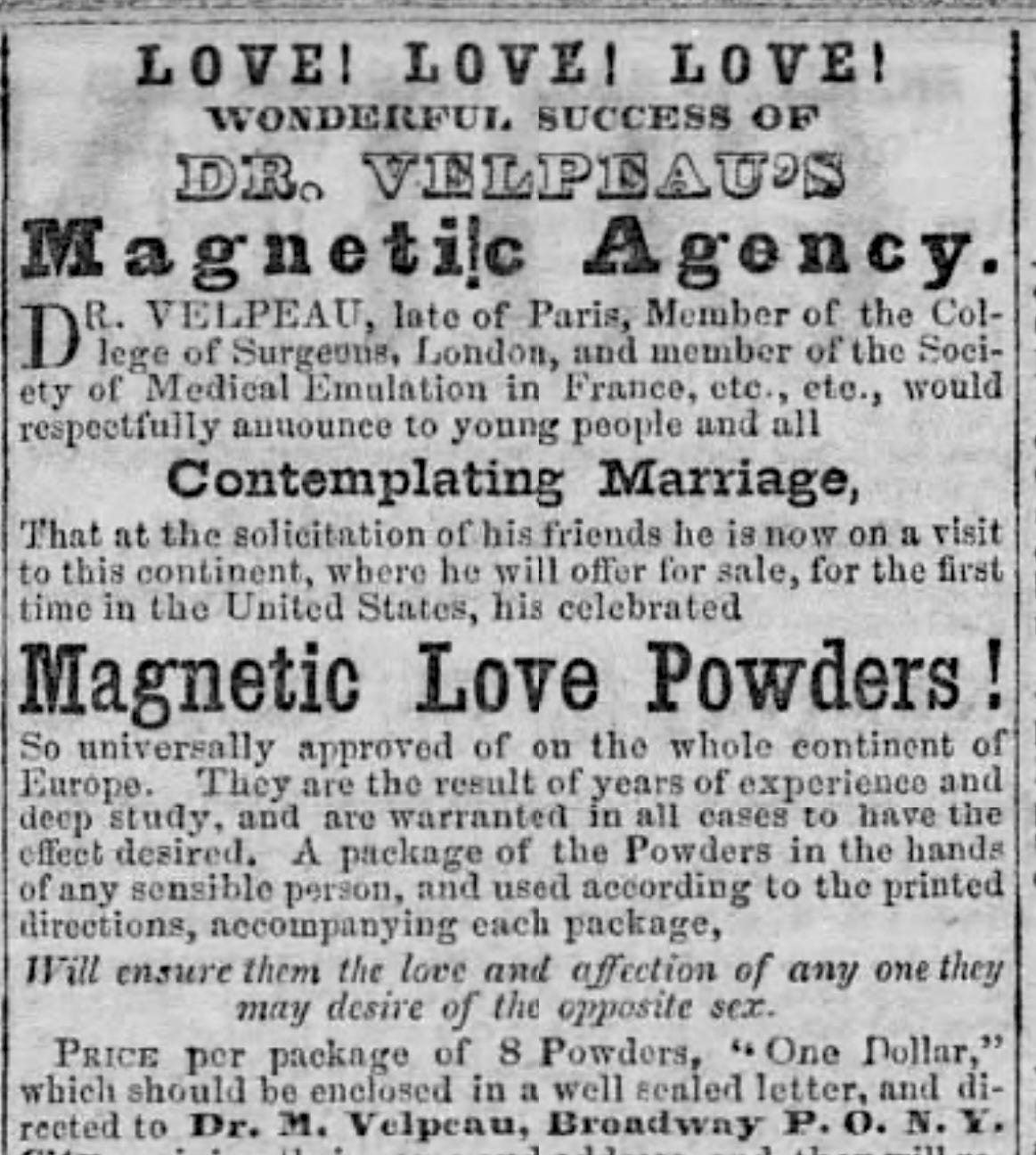

Dr Velpeau’s Magnetic Love Powders

In New York in 1855, entrepreneur J C Merrill sold Magnetic Love Powders, which were supposed to be secretly administered to the object of one’s affections. A critic joked:

Only think of it! For two dollars, any enterprising young man – no matter if he is as poor as an editor, and as ugly as a baboon, can through the instrumentality of these powders, make himself “lord” of the most charming lass of “sweet sixteen” to be found within the limits of our friend’s agency, which comprises four counties!