Blowing smoke: how tobacco companies flattered the medical profession

Doctors and their patients were a prime target of mid 20th-century tobacco advertising

'A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse.'

James I of England and VI of Scotland didn't hold back in his A Counterblaste to Tobacco in 1604. Yet, three hundred years later, smoking was still going strong, and those making money from it were always on the lookout for new markets and methods of promoting ‘this filthie noveltie’.

During the nineteenth century, cigars and cigarettes usurped the pipe in Europe and North America as the convenient and sophisticated way to inhale smoke. Objectors, however, cited smoking’s effects on the nerves and its tendency to impair the senses, weaken the constitution and harm the gums and teeth. It was thought to arrest growth in the young, affect the heart and circulation, and mar the natural beauty of the complexion – not to mention being a waste of money.

Confirmed links with serious diseases such as lung cancer would not come along until later, but early 20th-century commentators increasingly drew attention to the physical and moral evils of tobacco, especially among young men and women.

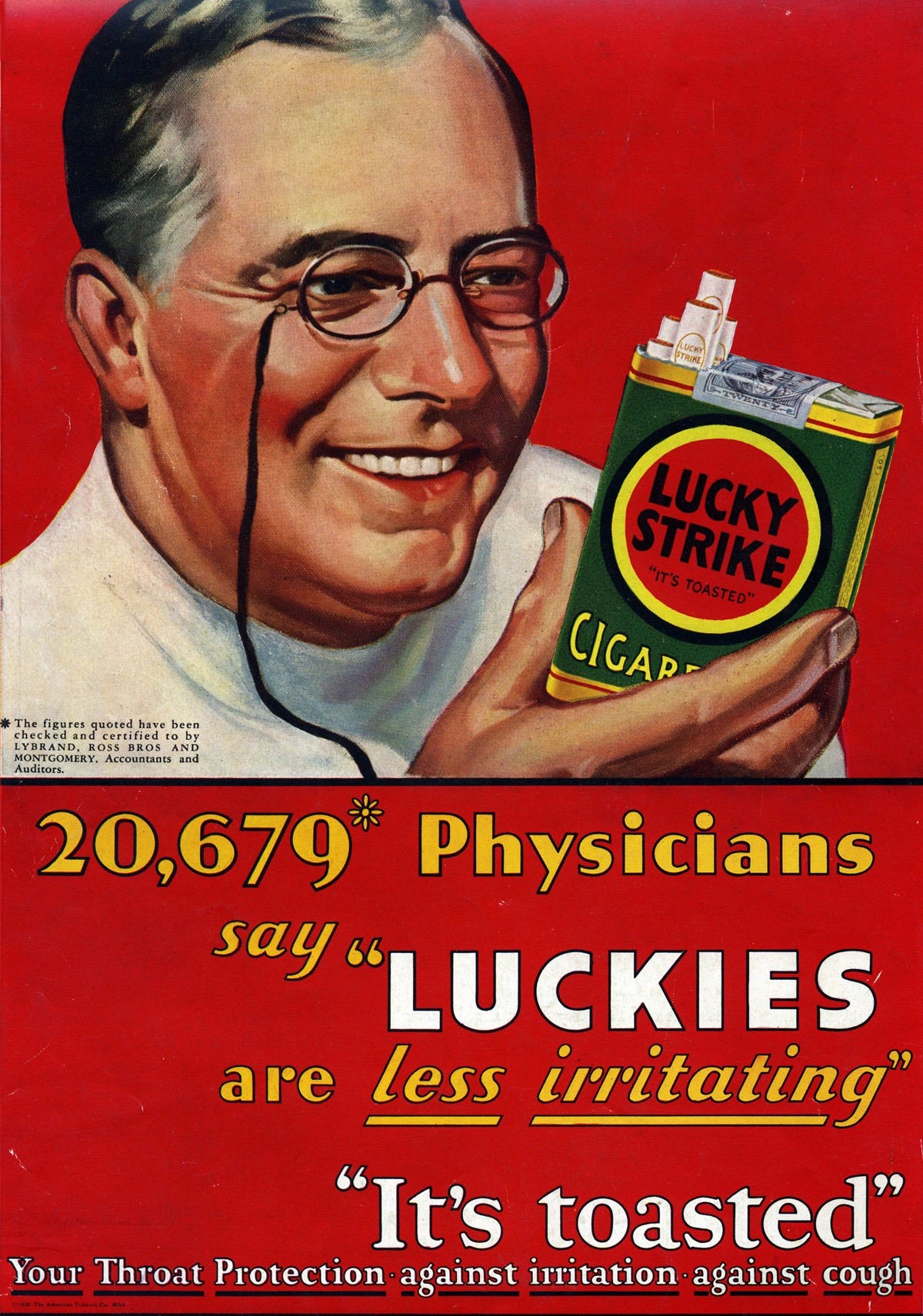

One way in which US tobacco companies responded to this threat was by turning to a figure that everyone could trust – the family physician. During the 1930s, images of avuncular, smiling, bespectacled men in white coats began to appear in advertisements, proclaiming that their favourite brand wasn’t one of the bad guys. This was not about encouraging people to take up smoking, but for companies to convince existing smokers that they offered the healthiest option. They alluded to scientific manufacturing processes that set their cigarettes apart from others’ inferior products.

Top brand Lucky Strike claimed in 1927 that 9,651 doctors agreed that the process of heat treatment (called ‘toasting’) was likely to prevent ‘Luckies’ from irritating the throat. In subsequent ads, the number grew to 11,105 and then 20,679 physicians, the specific figures lending an aura of authenticity to the claims.

The Liggett & Myers tobacco company jumped on the bandwagon of highlighting big numbers in its Chesterfield advertising – but if you read the following 1931 ad properly, you will see that the figures quoted are not related to smoking:

‘Night and day 152,503 physicians (in the U.S.A.) guard 122 million American lives!’

The ad goes on to talk about Chesterfield cigarettes, but this is a non sequitur – the company simply put doctors and cigarettes next to each other and let the customer’s mind create the link.

Many ads portrayed physicians as hard-working heroes, maintaining their energy and composure by means of a hastily snatched smoke in between saving lives. In this 1946 Camel advertisement titled ‘I’ll be right over’, the doctor is shown answering his bedside phone to an emergency.

‘When there’s a job to do,’ states the copy, ‘he does it. A few winks of sleep … a few puffs of a cigarette … and he’s back at that job again.’

Such marketing not only suggested to the public that the trusted local doctor approved of their cigarette choice – it also flattered the medical profession, encouraging doctors to see tobacco as an honorable companion through their demanding way of life.

Firms such as Philip Morris and R J Reynolds (who made Camels) went further in their targeting of doctors. Until the Journal of the American Medical Association stopped accepting tobacco advertising in 1953, its readers were regularly informed that 'More Doctors Smoke Camels than Any Other Cigarette'. Philip Morris hosted a ‘doctor’s lounge’ at AMA conferences, inviting delegates to come along to relax, chat, get letters typed up on free branded stationery – and, of course, smoke the abundant free samples.

In 1950, however, several studies were published showing a strong association between smoking and lung cancer. By interviewing lung cancer patients about their smoking habits, Ernst L. Wynder and Evarts A. Graham in the US, and Richard Doll and Austin Bradford Hill in the UK showed an unmistakable correlation. The results of these two largest studies were backed up by others. Doll and Hill concluded that 'smoking is an important factor in the cause of carcinoma of the lung.'

By 1960 there was no scientific doubt that cigarette smoking caused lung cancer, but the tobacco industry maintained that the issue was just a matter of opinion and that statistical evidence did not constitute proof.

Smoking might have declined in the West but the industry was quick to tap into 'emerging markets' elsewhere. In 2020, according to the World Health Organisation, there were 1.3 billion tobacco users globally – 36.7% of men and 7.8% of women. About 80% of them live in low-and middle-income countries, and the WHO estimates that tobacco is responsible for 8 million deaths every year.

Meanwhile, the rise of e-cigarettes has given the industry a new income stream, and health messages still weave through the advertising. Even the Covid-19 pandemic brought new opportunities to draw in customers, with some companies offering free hand sanitisers, face masks and those much-coveted toilet rolls with every order of vape juice.

Featured resource

For a fascinating, well-organised and huge collection of cigarette advertising images, visit the Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising website.

From The Quack Doctor archives: Victorian asthma cigarettes

The advertising connection between cigarettes and health pre-dated Big Tobacco’s efforts. In the 19th century, the cigarette became a handy way for asthma patients to take stramonium - a herbal medicine that relieved inflammation of the lungs.

‘Agreeable to use, certain in their effects, and harmless in their action, they may be safely smoked by ladies and children,’ ran the promotional copy for Cigares de Joy.

Read more about the use of stramonium for asthma at thequackdoctor.com

Featured event: Smoke and Ashes

6pm Friday 9 February 2024 at The Linnean Society, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BF, and on Zoom.

Moving deftly between horticultural histories, the mythologies of capitalism, and the social and cultural repercussions of colonialism, writer Amitav Ghosh reveals the role that one small plant - opium - had in the making of our world, now teetering on the edge of catastrophe. His latest book, Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s Hidden Histories, is out in the UK on 15 February.