Dame Nature has giv'n her a Doctor's Degree

In 1736, a celebrity bone-setter named Sarah Mapp became the talk of London

The bone-setter Sarah Mapp (c. 1706-1737) pops up a lot in collections of ‘eccentric characters’ or ‘quacks of old’; the few known details of her life were embellished in the Victorian era into quirky anecdotes about the gullibility of previous generations. Depending upon the angle of view, she is either a Hogarthian caricature, a remarkable healer or a rough-and-ready charlatan. The year 1736 formed her brief heyday, and her archetypal rags-to-riches-to-rags story has taken on the character of a folk tale. I have encountered her story so often that I fell into the trap of thinking ‘everyone knows this already’, so have always shied away from retelling it.

She is interesting to me, however, because she illustrates one of the less usual ways in which female practitioners could contribute to the medical marketplace long before the formal education of women doctors.

What was a bone-setter?

A bone-setter was a community healer who dealt with fractures, dislocations and other musculoskeletal disorders. If someone had a bone that was ‘out’, a bone-setter was the person to fix it. They did not have formal training but often, like Sarah Mapp, learnt their craft from the older generation. While some bone-setters had very little understanding of anatomy, others might have started out studying surgery or worked in a hospital. Some surgeons included the title of ‘bone-setter’ in their occupation, which suggests that the practice sat on the ill-defined boundary between reputable and ‘quack’ medicine.

The process of treating a broken bone was intuitive rather than scientific, and a good bone-setter would develop the knack through experience. A description in The Compleat Bone-setter (Thomas Moulton, 1657 ed.) shows the vagueness of the operation:

‘gently and moderately stretch and extend the member, till both parts of the Bone do meet together in their proper place: then form it together, till you feel you have brought it again to its natural form and figure, and the Bone be reposed in his due place.’

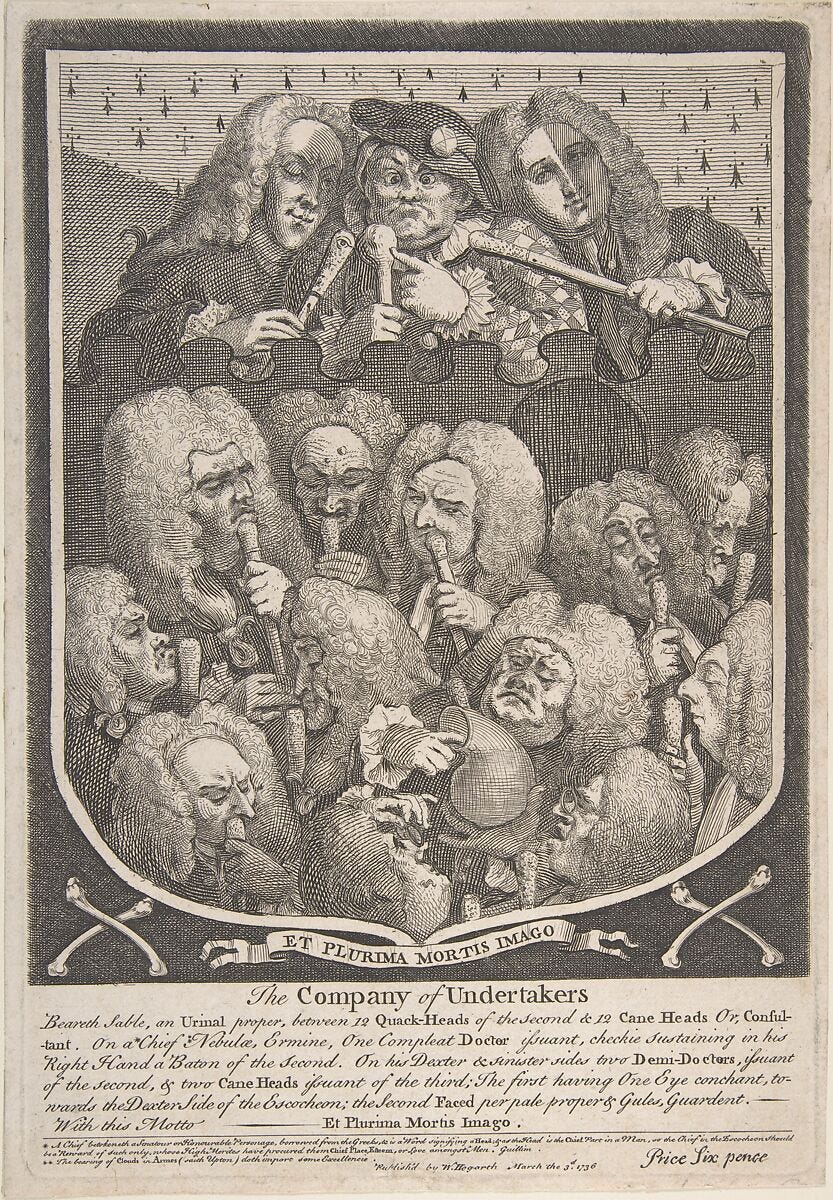

A sudden rise to fame

Sarah’s father John Wallin (or Wallen) was a bone-setter in Hindon, Wiltshire, and as Sarah grew up she proved to have both the aptitude and physique to follow in his footsteps. She was what one might now describe as an ‘absolute unit’ and could wrangle with a dislocated joint for as long as it took to sort it out. The only pictures we have of her are caricatures – first in William Hogarth’s The Company of Undertakers, and secondly an engraving by George Cruikshank, who was born decades after her death and had only Hogarth’s image to refer to. She is presented as a beefy, cross-eyed character dressed in a harlequin’s outfit and carrying a bone as a physician might carry his cane.

Very little information survives about her early life, but contemporary accounts suggest she worked alongside her father until 1736, when they fell out and she left Hindon, pitching up at Epsom where the racecourse must have provided her with a constant supply of injuries to repair, and where health-seeking visitors congregated for the famous salts. Somewhere along the way she became known as ‘Crazy Sally’ on account of her larger-than-life character, disregard for social norms, and tendency to spend her earnings on drink.

Her presence at Epsom soon attracted the attention of both rich and poor, and demand for her help became almost overwhelming. In August 1736 her patients included a boy ‘whose arms had been quite useless from the time of his birth’, and a 14-year-old girl whose ‘Shoulder, Elbow and Wrist were out’.

Her practice required strength and tenacity, as shown in the case of this young man:

‘Last week the Son of Mr Potts, an Oil-man in Gracechurch-street, about twenty-five Years of Age, (who has been lame with his Elbow out of Place for twenty-two Years) was carried to her at Epsom: she struggled with him to set it near three Quarters of an Hour; but he was in such Pain, and she so weary, that she was obliged to go out to rest herself: but returning soon after, she had the good luck to set it.’ (Weekly Miscellany, 21 August 1736)

The papers reported that ‘People of all Ranks flock daily to share in this Happiness’ and speculated that she was earning 20 guineas a day. Her income often came in the form of large one-off gifts from impressed wealthy people, which meant she could provide free treatment for those who couldn’t afford to pay. She began to make regular trips to London, where she received patients at the Grecian Coffee House in Devereux Court, often observed by members of the aristocracy. In October 1736, she reportedly cured Sir Hans Sloane’s niece, whose shoulder-bone had been ‘out’ for nine years.

Of course, some were sceptical about her abilities. One story has it that a group of surgeons sent a patient with a fake injury to catch her out – she immediately realised he was an impostor and wrenched his wrist so hard that she dislocated it, telling him to go and have it sorted out by the fools who had sent him.

A brief marriage

On 4 August 1736, Sarah Wallen married Hill Mapp, a mercer’s footman to whom she had taken a fancy. Her friends attempted to stop the wedding, perhaps recognising that Mapp was a wrong ‘un, but they went ahead and she acquired the name by which she has been known ever since. Within a fortnight, however, Hill Mapp had run off with his wife’s savings of more than 100 guineas. The Kentish Weekly Post (21 August 1736) reported that:

‘her Concern was at first very great; but as soon as the Surprize was over, she grew very gay and seem’d to think the Money well disposed of, as it was like to rid her of a Husband.’

That September, a couple of newspaper snippets did claim he ‘is return’d, and has been kindly receiv’d’, but even if this is true, it was not for long – records show he married someone else the following year, while Sarah was still living.

He was not the only one in Sarah’s life with a relaxed attitude to marriage. Her sister Mary Wallin was an actress, who at one point played the role of Polly Peachum in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera. This has led to some confusion in narratives of Sarah Mapp’s life, because a more famous performer, Lavinia Fenton, (who married the Duke of Bolton) also played this part and is often erroneously portrayed as Mapp’s sister. On Valentine’s Day 1728, Mary wed John Sommers in a ‘Fleet Marriage’ (the Fleet Prison was claimed to be outside the Church’s jurisdiction and was a location for clandestine marriages before the Marriage Act of 1753). They presumably went their separate ways because on 27 April 1729 she married another man named George Nicholas. In December 1736, Mary, under the name Mary Sommers, was indicted for bigamy and tried at the Old Bailey but acquitted.

Mrs Mapp and Hogarth

William Hogarth’s A Consultation of Physicians, or, The Company of Undertakers (1736) positions Sarah Mapp within a triumvirate of celebrity quacks – the others being the oculist John ‘Chevalier’ Taylor and Joshua ‘Spot’ Ward, proprietor of Ward’s Pill and Drop. Beneath them is a collection of physicians, most of whom are shown sniffing a pomander on the end of a cane – this would typically be filled with aromatic substances to ward off infection. The pomander-sniffing symbolises arrogance and suggests a desire to distance themselves from their patients.

Hogarth turns the medical hierarchy on its head, placing a female irregular practitioner above the male physicians and implying through the motto Et plurima mortis imago – ‘And many are the faces of death’, that a patient is no better off with a university-educated doctor than with a quack.

Social life and satirical song

Mapp, Taylor and Ward did know each other and on at least one occasion dined together at Ward’s house in Pall Mall, which I imagine must have been an entertaining evening! Mapp’s sense of fun comes across in an account of her attending a play called The Wife’s Relief, or the Husband’s Cure (possibly a modernisation of John Shirley’s The Gamester, 1633), at the Theatre Royal in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where she shared a box with ‘Chevalier’ Taylor. The performance also included a pantomime called The Worm Doctor, and when one character was clearly meant to be a send-up of Taylor, Mapp larked about for the audience, pointing at her companion. Another character called ‘Harlequin Female Bone-Setter’ appeared and she took it in good part, laughing along and seeming ‘highly delighted’. According to the Gentleman’s Magazine Historical Chronicle for October 1736, the performance included the following song (probably to the folk tune Derry Down):

You surgeons of London, who puzzle your pates To ride in your Coaches, and purchase Estates, Give over, for Shame, for your Pride has a Fall, And the Doctress of Epsom has out-done you all. What signifies Learning, or going to School, When a Woman can do without Reason or Rule? Who puts you to Nonplus, and baffles your Art, For Petticoat-Practice has now got the start. In Physick as well as in Fashions, we find The newest has always its Run with Mankind: Forgot is the Bustle ‘bout Taylor and Ward; Now Mapp’s all the cry, for her Fame’s on Record. Dame Nature has giv’n her a Doctor’s Degree, She gets all the Patients, and pockets the Fee; So if you don’t instantly prove her a Cheat, She’ll loll in her Chariot whilst you walk the Street.

As in Hogarth’s caricature, Sarah Mapp’s success allowed satirists to mock the orthodox medical profession, who might have been better educated but perhaps lacked the ability to relate to and gain the trust of people from all walks of life.

Ultimately, Sarah Mapp’s celebrity was fleeting. Whether heavy drinking affected her abilities, whether her sister’s predicament affected people’s opinion of her, or whether the public simply moved on to the next wonder of the age, it is difficult to tell. She died at her lodgings in Seven Dials in December 1737, ‘so miserably poor that the parish was obliged to bury her’, and she lies in an unmarked grave at St Giles-in-the-Fields, Holborn.

13 September 2023, 10.30am ‘Fine, Healthy Leeches’: Victorian Medicine in St Neots. Liz Davies explores the diseases, remedies and variety of medical practitioners in the local area during Queen Victoria’s reign. Free to attend.

14 September 2023, 6pm: Medieval Pharmacy: from Text to Practice.

Dr Iolanda Ventura presents this online event, hosted by the Old Operating Theatre.

15 September 2023, all day: Roman Medicine and Healthcare in Britain. This study day at Wroxeter includes a talk, a guided tour of Wroxeter Roman site and a practical session where you will have the chance to attempt some Roman surgical techniques!

18 September 2023, 2pm: Sickness and Health in the Amersham Area

Briony Hudson looks at Amersham’s health past, from plague and pest house, workhouse and hospital, to wartime nurses and pioneering doctors.

25 September 2023: Fortitude. This free exhibition opens at the Royal College of Physicians London, sharing the challenging and inspiring stories of healthcare workers’ experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic. Runs until May 2024.

30 September 2023: The University of Edinburgh’s Anatomical Museum begins its monthly open days again after the summer break.

October: It’s London Month of the Dead! Antique Beat and A Curious Invitation curate this haunting array of talks, walks, workshops and performances.