Eight years in cocaine hell

A Chicago society lady suffered a disastrous change in her fortunes when she tried to cure a cold.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Annie C Meyers occupied a privileged position among Chicago’s top set. The wealthy widow of a naval captain, she enjoyed everything that fashionable fin-de-siècle society had to offer. She was part of the inner circle of leading socialite Bertha Palmer, and was a member of the Board of Lady Managers organising the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Everything changed in 1894, when she came down with a heavy cold.

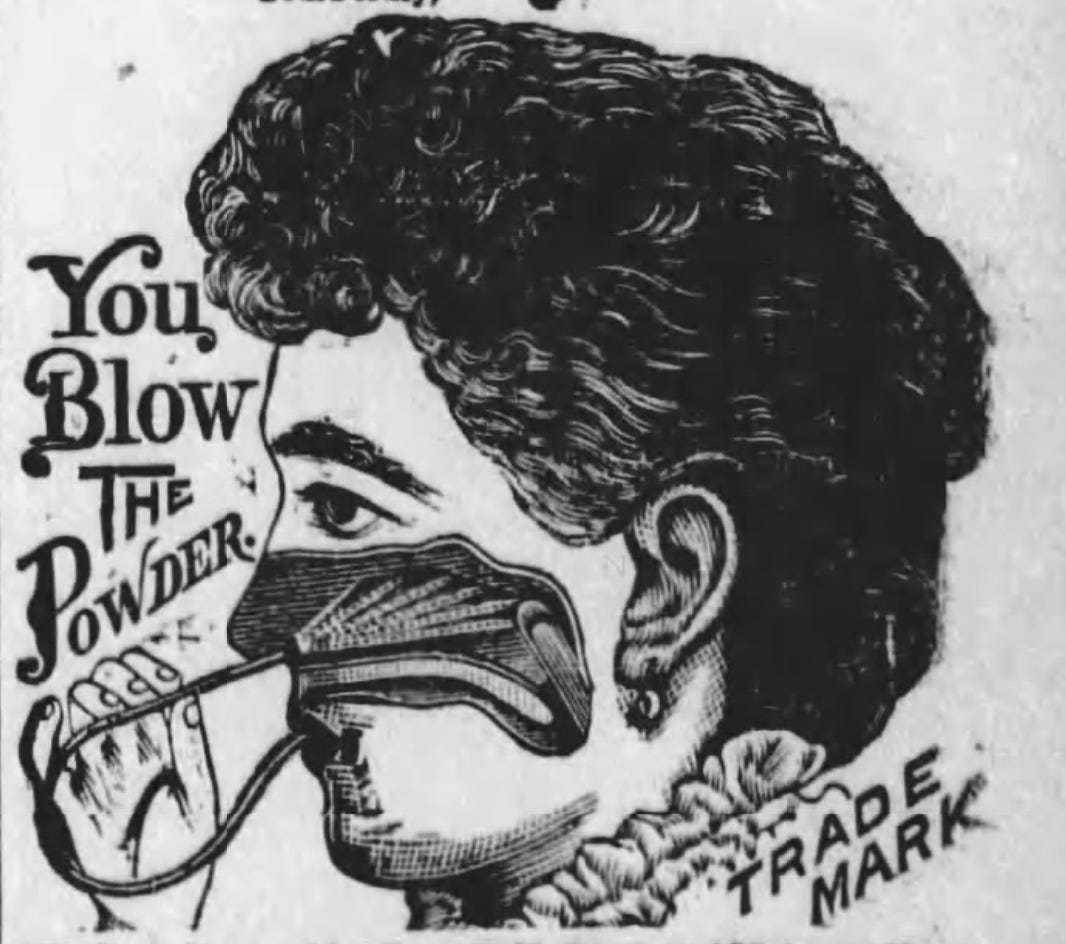

While discussing some minor legal matters, her lawyer noticed her suffering and suggested she try Birney’s Catarrh Powder, a patent medicine for colds, flu and hay fever. The product’s trademark (below) showed how to administer it by using a tube to blow the powder up the nose. Its principal ingredient was cocaine – perfectly legal at the time – and within weeks Mrs Meyers had joined the ranks of the ‘cocaine fiends’ who would do anything for their next fix.

We know about Meyers’ addiction because, in 1902, she published a short and shocking memoir called Eight Years in Cocaine Hell. This was printed by the St Luke Society – a purportedly religious organisation that ran a sanitarium for the rescue of drug and alcohol addicts. As such, the book praises the society and its president Orlando E Miller rather more than they deserved. Miller was a dodgy piece of work and, by chance, the darker side of his activities came out shortly after the memoir’s publication. Meyers wrote:

From a well-balanced Christian woman, I became a wretched physical and mental wreck. My thoughts were only for the accursed poison, cocaine, that was dragging me down to destruction; walking the streets of this wicked city, wandering from place to place, night and day, insane with grief and remorse, every hope of success, every promise of prosperity, dashed to the earth by this demon!

She became homeless and drifted from city to city, begging and shoplifting to fund the $10 a day she spent on cocaine. A full-size bottle of Birney’s Catarrh Cure cost just 50c, and was supposed to last a hayfever sufferer six weeks.

Meyers often got arrested for being under the influence or for shoplifting, but repeatedly escaped charges – in part due to her former social status, and because the police and store managers tended to see her as a hopeless object of pity. It was the cocaine committing the thefts, not her. Having stolen expensive goods from Marshall, Field & Co, she was apprehended by the store detective.

The manager said, ‘If we let you go, will you keep out of the store?’ I answered, ‘Gentlemen, excuse me while I take a blow of my cocaine,’ as I had to take it about every five minutes. They asked me to show them again, and several different times, while there, how I took it. The manager spoke kindly to me, saying, ‘Poor unfortunate woman, God has been merciful to me and I will be merciful to you. You are free.’

As Meyers’ addiction progressed, she got involved with a gang of forgers, who kept her ‘well loaded up with cocaine’ in return for using her former good name as an introduction to wealthy victims. She also began performing what she called her ‘Cocaine Dance’ in the sporting houses (brothels) and collecting money from the punters. In her efforts to avoid the police, she found herself hiding out in all manner of unsavoury places – on one occasion, she crawled into a disused furnace and found some bones wrapped up in a charred and blood-covered silk waistcoat.

At the rock bottom of her addiction, with no money for her next fix, she took desperate measures:

I deliberately took a pair of shears and pried loose a tooth which was filled with gold. I then extracted the tooth, smashed it up and taking the gold went to the nearest pawn shop (the blood streaming down my face and drenching my clothes), where I sold it for 80 cents.

Meyers’ former church congregation shunned her, but her sister, Mary McCabe, never gave up on trying to protect and help her, even though Mary must have been experiencing a hell of her own. Eventually, when Meyers was locked up in the Chicago Bridewell, Mrs McCabe and O E Miller of the St Luke Society secured her release on condition that she would be admitted to the sanitarium.

My hair was mostly out. A part of my upper jawbone had rotted away. My teeth were entirely gone. My face and my entire body were a mass of putrefying cocaine ulcers. I weighed only about 80lb and it would be hard to conceive of a more repulsive sight.

This was in 1900; from that time on she made a gradual recovery under the treatment of the St Luke Society. At least, that is what her book says; as it was printed by the society, it comes across partly as a promotional vehicle and contains a full-page portrait of O E Miller captioned as the man who rescued her.

The St Luke Sanitarium, however, was not quite the haven of Christian compassion portrayed in Eight Years in Cocaine Hell. When a fire broke out there in 1902, nine patients died because the attendants fled and left them in a locked ward. A doctor also died jumping from a window to try to escape. Burnt bodies were found in straitjackets and there was evidence of patients desperately trying to rip the bars from the windows.

The sanitarium had no licence to operate as a hospital, although the Chicago Health Department tolerated it to some extent as a useful dumping ground for drunks picked up by the police. During the investigations after the fire, details emerged of O E Miller’s treatment protocol. All patients, whatever the nature of their addiction or mental state, received the same medicine, injected hypodermically. Miller would not disclose the formula, even to his own staff. Before the fire, deaths were already frequent at the sanitarium, and it transpired that the medicine was morphine; overdoses were easily given. The fire brought an end to the sanitarium but not to Miller’s various money-making schemes, which shifted to the UK and saw him imprisoned for manslaughter in 1914.

Annie C Meyers recovered from the physical effects of addiction, but it wasn’t a smooth redemption arc. In 1906 she was arrested twice for shoplifting, saying that cocaine had caused persistent kleptomania, but it is not clear whether she had gone back to using it. Eight Years in Cocaine Hell was part of a heightening discourse about the dangers of addictive drugs and their often secret inclusion in patent medicines. But while legislation such as the Pure Food and Drugs Act made steps towards addressing the issue, substance abuse disorders continue to affect more than 46 million people in the USA today.