Hooked on a cure: a tale of tapeworm troubles

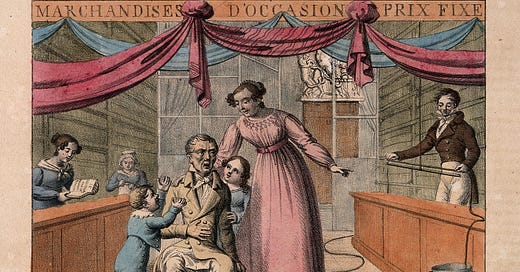

A gentleman in 18th-century France went to horrifying lengths to cure himself of a worm infestation

The Gentleman’s Magazine printed a communication in 1750 from a resident of Lyon. The letter was originally published in French in the Mercure de France in 1749, and told the story of the writer’s heroic efforts to rid himself of tapeworm. The following details are perhaps what I call NSFS (Not Safe For Stomach) but I know many Quack Doctor readers enjoy the weird and revolting side of things – so if you are not of a sensitive disposition, read on.

This gentleman had been plagued for many years by tapeworm – probably the beef variety, Taenia saginata, which can grow to gargantuan lengths within the digestive system. He suspected that they had been there all his life, for he remembered ‘always to have felt it upon every change of weather, and agitation of mind, like a small whisp of horse hair in the pharynx.’

He suffered pains in the oesophagus, tremors, fits of coughing, insomnia, flatulence, itchy and blotched skin and a range of other symptoms that left him feeling like ‘my whole body seemed to be a lump of dead and putrefying flesh.’

Eventually, he consulted some physicians, who believed he had a blood disorder. They therefore prescribed bloodletting and purging, assuring him afterwards that his blood was now mended and that he would gradually recover. There is an element of dry humour in the writer’s comment:

‘However after this gradual recovery, effected by continuous evacuations, had continued 10 years, I could not help thinking myself worse.’

The gentleman was by this time emaciated, with a bloated belly and difficulty eating. A country surgeon advised him to have three quarts of blood removed and to use a decoction of watercress as a diet drink, but three weeks of this regime failed to improve things.

A hint of progress occurred when he tried Ailhaud’s Powders, a well-known patent medicine with violent laxative effects. The first dose expelled a long portion of worm, but although he continued taking the powders, nothing else happened.

At least he now had proof of the cause of his illness; he returned to the doctors who had treated him before, but was once again unimpressed. They ‘produced a very considerable effect, for in this time they had drawn from me all my money, and encreased my malady.’ He felt dismissed as ‘a fanciful wretch, whose disorder had no existence but in imagination.’

He then tried an unnamed quack medicine, whose proprietor got him to live on a diet of bread and olive oil for four months. Meanwhile, the doctors suggested he had venereal disease, which led to social stigma on top of the physical suffering.

Our gentleman next resorted to a ‘madman at Auvergne’, who initially gave a somewhat random diagnosis of gutta serena (an eye condition) but then decided it was dropsy (oedema). This meant the man had to undergo the unpleasant process of tapping – puncturing the skin and inserting some form of drain to allow the fluid to escape. As well as being painful due to the unavailability of anaesthetics at the time, there was a high risk of infection. The Auvergne practitioner made three incisions, but no fluid came out, so ‘he forced an instrument round between the skin and the flesh, the noise of the laceration made me tremble.’ The patient had, however, got to the stage where ‘my pain was so intense, that no operation could greatly increase it,’ and from then on he resolved to experiment upon himself with all sorts of remedies, however dangerous.

He began by wandering the countryside, eating whatever herbs he could find and making a note of how each one affected him – taking the view that if he accidentally poisoned himself, being dead could be no worse than his current situation. Hedge-hyssop abated his symptoms enough to give him the energy to read, and through studying medical books he found a purgative that finally started to dislodge the worms. He does not tell us what this medicine was, but he took it every two days for a year and it caused the expulsion of between two and ten ells of tapeworm per dose. A French ell was a unit of measurement corresponding to 54 inches (137.2cm) so that’s a lot of worm! He claimed that over the course of the year, a total of 900 ells (three quarters of a mile!!) emerged from his beleaguered anus.

The worms, however, were clearly still alive and continuously growing inside him, so it was time for even more drastic measures. Understandably, the situation seems to have taken over the gentleman’s life and made him quite obsessive about finding a cure – or dying in the attempt.

Hence:

‘I made some small hooks of lead, with 3 points, like an harping iron, and fastened them with a piece of thread to a leaden bullet, in order to swallow them.’

He did indeed swallow them, to the horror of his friends, who were supposed to be looking after him during the experiment but squeamishly abandoned him. Rather than lacerating his intestines (a danger of which he was well aware), the invention brought away large sections of worm – although seven hooks remained in his body for more than three months.

The gentleman adapted his design to feature a serrated hook attached to a silk thread hung from a spoon handle; thus it could only descend a short way into his oesophagus, where he believed the worms’ heads to be. Pulling it back up proved too much even for this madlad, so he cut the string and swallowed it. Within a few days, a whole worm, complete with hook, arrived in his chamberpot, and subsequent microscope inspection showed it to have a head like a cat, but no eyes. Further use of the hooks dealt with his remaining worms, which came out alive, and the poor chap’s ‘dreadful narrative’ was finally over.

By means of his correspondence, he helpfully informed readers that the hooks were a safe and effective remedy for tapeworm – at least until ‘some persons of greater sagacity may perhaps discover something better.’

HistMed Highlights

MEDIEVAL SURGERY: 📜 🪚 Northampton Museum and Art Gallery welcomes Steve Bacon of Live’n History to explain the theory of the four humours and demonstrate the skill of the medieval surgeon. Live leeches add the eek factor and audience participation is encouraged! Thursday 28 March 2024, 10.30am, tickets £3. Book here.

EXAMINING THE EYE: 👁️Surgeons’ Hall, Edinburgh, launches its new temporary exhibition examining the history of medicine’s oldest specialty, ophthalmology, on 29 March. On 1 April, human remains conservator Cat Irving presents a lunchtime talk on The Eye in Myth and Science, looking at the ways our understanding of the eye has changed through time. How did this delicate organ become the site of one of the earliest procedures? Did a Scottish king try his hand at operating on the eye in 1501? Why did a local saint pluck out her eyes? And what on earth was Issac Newton doing when he pushed a bodkin round the back of his eye to try and figure out how it worked? Monday 1 April 2024, 1.15pm. tickets £3. Book here.

DRINK, DEATH AND DEBAUCHERY: 🫗🪦The Foundling Museum invites you to join a guided walking tour that takes in the colourful history of London’s West End around St Giles, Seven Dials and Covent Garden. Learn about Hogarth’s Gin Lane and the notorious gin craze of the 18th century, plus the history of the gallows, plague pits and prostitution. Saturday 30 March 2024, 11am, starting at the Dominion Theatre, Tottenham Court Road. Tickets £25 (£20 concessions). Book here.

More tapeworm fun from The Quack Doctor!

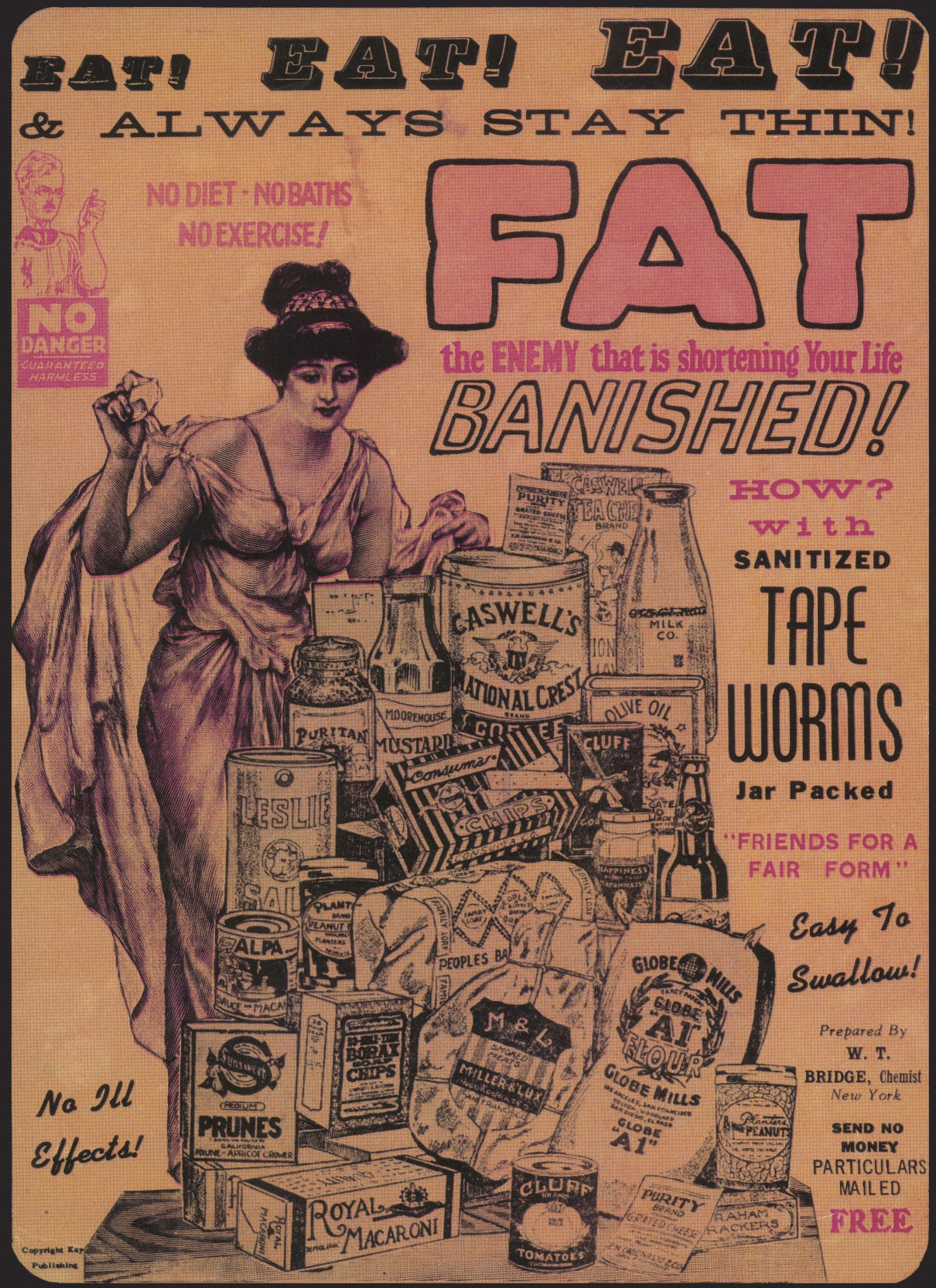

An advertisement for ‘Sanitized Tape Worms’ has become a staple of internet lists featuring shocking historical cures – but what’s the truth? Did Victorian women really follow the ‘tapeworm diet’ in order to shed unwanted pounds? My article Eat! Eat! Eat! Those notorious tapeworm diet pills shows why I think the answer is ‘no’.