'How the Devil can I answer?': violence at Apothecaries' Hall

An 1830s medical student ended up in hot water after losing his cool in an exam.

When sitting an exam on which one’s future career depends, it is advisable not to fly into a rage and hit the examiner over the head with a blunt instrument. In December 1836, medical student Charles Wadham Wyndham Penruddocke made this mistake, and ended up in big trouble.

The exam to become a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries was no doubt daunting – the candidate had to sit at a table with a panel of interviewers and answer their questions about a range of subjects including chemistry and materia medica. If he got through this ordeal, he would find out straight away that he was now a qualified apothecary and could unleash his healing powers on the public. If his answers were not up to scratch, however, he would be rejected and left to ponder whether to try again after six months, or to choose a different career.

Charles W W Penruddocke (1813-1886) was the son of Captain Thomas Penruddocke of the 3rd Foot Guards, and was linked to an old parliamentary family, the Penruddockes of Compton Chamberlayne in Wiltshire. He had some private income and was not going to rely solely on medicine for a living, but was nevertheless making an attempt at qualifying. He must have completed an apprenticeship, done hospital experience and got certificates to confirm he had attended lectures before being eligible for the exam. Like most aspiring medical men of the time, he was aiming for the dual qualification of ‘College and Hall’. He had already passed the exams of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and just needed his apothecary certificate in order to launch himself into general practice.

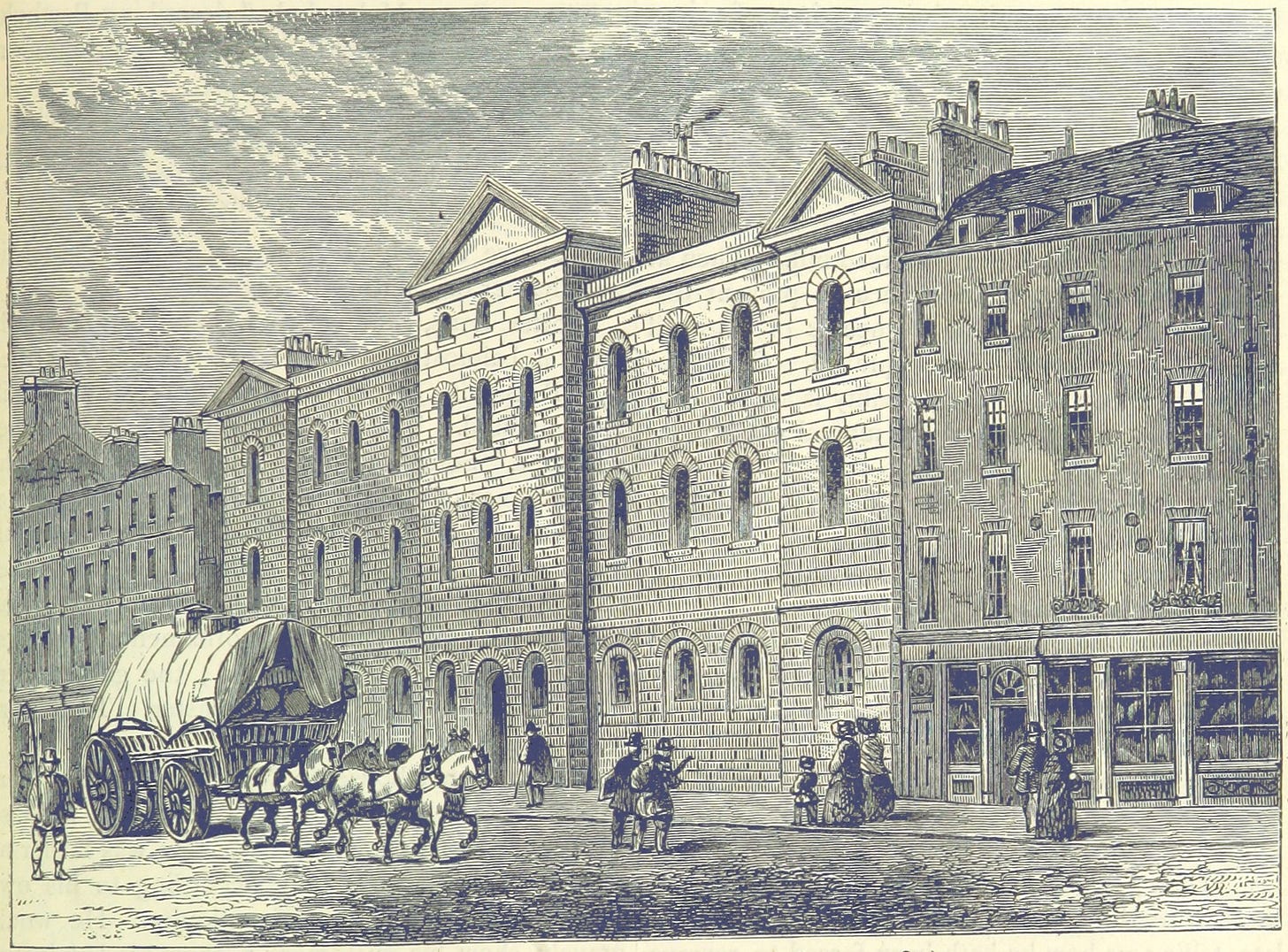

On 22 December 1836 he arrived at Apothecaries’ Hall at about 8 o’clock in the evening and was allocated to the table of Mr Este, Mr Randall and Mr Tegart. It quickly became clear to these gentleman that he did not know his stuff.

An exchange on the identification of cubebs (used to treat gonorrhea) was typical:

Mr Este: ‘Don't you recollect it is a species of pepper?’ Penruddocke: ‘Oh yes, I know it very well.’ Mr Este: ‘Don't you know it is used in a specific mucous discharge?’ P: ‘Oh yes.’ Mr Este: ‘Have you not seen it used in the Lock hospital?’ P: ‘Oh yes.’ Mr Este: ‘Don't you recollect it is cubebs?’ P: ‘Oh yes, I know it very well.’

In this situation, the done thing was to call an examiner over from another table for a second opinion, hence Mr Thomas Hardy (a retired surgeon, not the depressing novelist nor Nelson’s flag captain) got involved.

Penruddocke not only lacked knowledge but also presented an obnoxious demeanour throughout the exam, chewing pieces of sarsaparilla with what Mr Hardy described as ‘an air of more than indifference—indeed I may say of defiance.’ Hardy felt Mr Este was being too soft on this wastrel and should stop spoon-feeding him the answers, though he put it more diplomatically than that. Penruddocke became irritated with the questioning and said:

‘How the Devil can I answer, when I am badgered in this way?’ He went on: ‘I wish you would examine me in anatomy—I have studied that part of my profession—I like anatomy—I have lived in the dead-house.’

Although anatomy and physiology were included in the Apothecaries’ qualification, it was not worth proceeding to that part if you couldn’t do the materia medica, chemistry and botany elements.

Penruddocke had about his person a fashionable self-defence implement called a life-preserver. This cord-bound short stick with a ball of lead on each end was designed to help the wealthy young man-about-town fend off muggers and murderers. While the objective was to preserve the carrier’s own life, the device could also be used to un-preserve someone else’s.

When Mr Este at last gave up on him and brought the examination to an end, saying ‘I am very sorry Sir, but I cannot consider it my duty to recommend you to the court to receive your certificate’, Penruddocke announced: ‘Do you think I am going to be disgraced before my family by such a set as you are—no, be d___d if I will be—I would die first—I would swing for it’, rose from his chair, whipped out the life-preserver and clobbered Mr Hardy. As the other examiners rushed to tackle him, they too were struck. Mr Hardy felt blood gush from a wound on his temple; as it flowed into his eyes he grabbed the table to support himself and managed to stay conscious. One of his colleagues sent out for a policeman and Penruddocke was immediately taken into custody.

Mr Hardy had a severe contused wound, but his skull was not fractured and he recovered over the next few weeks. Meanwhile, Penruddocke was in Newgate Gaol awaiting trial at the Old Bailey – and for all his bravado about ‘swinging for it,’ he was bricking it that he really did face hanging. The charge was that he had assaulted Hardy ‘with intent, feloniously, wilfully, and of his malice aforethought, to kill and murder him’, and this was a capital offence.

Although Penruddocke had brought a weapon to his exam, there was insufficient evidence that he intended to kill anyone, and on 1 February 1837 the jury of the Central Criminal Court returned a verdict of ‘not guilty’. This was not the end of the matter, however, for the Society of Apothecaries applied for him to be detained and tried for the lesser offence of common assault. In April that year, Penruddocke was found guilty at the London Sessions of assaulting Mr Hardy, and sentenced to a year in the Giltspur-street Compter, a small prison in Smithfield.

Imprisonment took its toll on Penruddocke’s health, which had already been precarious and was, in his view, the cause of the nervous irritability that had led him to lash out. In a letter to the Court of Examiners of the Society of Apothecaries dated 6 July 1837, he eloquently appealed for their intervention in persuading the Home Secretary to terminate his sentence.

You are aware that on the 5th April last, I pleaded guilty at the London Sessions to the charge of assaulting Mr Thomas Hardy one of your Court and since that day I have been suffering punishment in the above prison. You also know that prior thereto I was imprisoned for six weeks on the same charge and underwent all the anxieties of a trial involving my life. You will not therefore be surprised to learn that from the pressure of these mental and bodily sufferings I have sunk under despondency into a low fever which has for three weeks confined me to my bed and greatly endangered my life. The crisis of that disease, has I thank God since passed and the danger greatly decreased but my debilitation is such and my gloominess so excessive that unless they are speedily relieved a relapse is greatly to be feared.

The Court of Examiners did take pity on him and supported his petition for release, which was accompanied by several character references testifying to his mild demeanour and humane attitude to patients in the hospitals where he had studied. On 28 July 1837, his sentence was remitted and he was free to go, although he remained under recognizances to remain out of trouble for five years.

Having already qualified as MRCS before the debacle at Apothecaries’ Hall, Penruddocke could in theory have practised as a surgeon (without being allowed to dispense medicines), but he does not appear to have done so – the 1851 census lists him as ‘Surgeon, MRCS England, not in practice’. He had family money to fall back on but nevertheless became bankrupt in 1863. There is no record of any further outbursts of violence – he might not have bothered to learn his materia medica, but prison provided him with a more important lesson.

From The Quack Doctor archives

Mr Grimstone and the revitalised mummy pea

In a Highgate garden known as the Herbary grew plants destined to invigorate nostrils all over the world. Savory, rosemary and lavender scented the air, while orris-root thrived under the carefully cultivated soil. Dried, powdered and mixed with salt, they would become Grimstone’s Eye Snuff and Grimstone’s Aromatic Regenerator.

In 1844, however, the Herbary became the site of an even more miraculous regeneration – the supposed resurrection of a plant that had lain dormant for millennia in an Ancient Egyptian tomb.

Sources

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 9.0) January 1837. Trial of CHARLES WADHAM WYNDHAM ENRUDDOCK (t18370130-521). Available at: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t18370130-521 (Accessed: 5th January 2024).

Charles Wadham Wyndham Penruddocke, Home Office Criminal Petitions Series 1, HO17/101/33