Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

This article has previously appeared on thequackdoctor.com.

A horse, tacked up but riderless, grazed peacefully on the north bank of Oregon’s Siuslaw River one December morning in 1904. When the search party saw it, they shouted out in hope, but no human response broke the after-storm silence of the damp air.

Dr Richard Henry Barber of Gardiner, OR, hadn’t been seen since he set off on a gruelling twenty-mile journey to an emergency in the town of Florence the night before. He had planned to ride along the Pacific shoreline, fording a flooded creek, then cross the Siuslaw by boat. But the creek wasn’t flooded after all; he didn’t notice it and later mistook the Siuslaw for the place he was supposed to ford. No one could know how far he got into the dangerous swim before he realised his mistake, but there was no turning back.

The search party found Dr Barber’s body in a waterlogged pit underneath the jetty. His watch had stopped at 8 o’ clock. Evidence from the scene suggested he had reached the shore alive and tried to open his hip flask, but, in a confused and hypothermic state, had stumbled into a death trap. The local community mourned the loss of their popular physician, who had also served as captain in the volunteer corps. His wife, Dr Jean Barber, was left to continue their medical practice alone.

There could be no doubt that Dr Barber was dead. His body had been recovered, identified and buried. So it is surprising that no one took much notice of his reappearance in England two years later.

In 1906 Britain’s General Medical Council – the body responsible for administering the Medical Register – received a letter from Dr Richard Barber stating that he had returned from Oregon and now resided at 52 Tunnel Road, Liverpool. Over the next few years, he updated his address several times as he moved around the country acting as assistant to various physicians.

It was while running his own practice at Treeton in South Yorkshire that ‘Dr Barber’ aroused suspicion. His assistant, Dr Henry Bond, suspected that his boss was not fully qualified; he had mentioned ‘a skeleton in the cupboard’ and ‘would not talk of proper medical subjects, and would not go to operations.’ Bond informed the Medical Defence Union, who wrote to Dr Barber in September 1912 asking for help establishing the identity of the gentleman who had lived and died in Oregon.

Immediately on receipt of the letter, the doctor packed his bags and disappeared, leaving the practice to Dr Bond, who never heard from him again. A couple of months later, he resurfaced in Liverpool – and by this time, the police were after him. They just needed proof that he wasn’t the real Dr Richard Henry Barber – and they knew exactly who could help them.

Dr Jean Barber (1865-1927) was Scottish by birth and had studied medicine in Edinburgh without qualifying. After emigrating to the US with her husband, she received her diploma in 1894 and they worked in Portland and Yoncalla before establishing a small hospital at Gardiner in early 1904. In her bereavement, it slipped her mind that her husband was still on the Medical Register back in Britain.

In 1912, rumours about the fake ‘Richard Barber’ began to circulate in Oregon, so when Jean Barber received a cablegram from Scotland Yard that November, she was ready for action. The very next day, she set off for Portland, and thence undertook the 3,000-mile journey to Quebec City, where she boarded the Empress of Britain bound for Liverpool. On the way, she received a message asking her to go straight to the Adelphi Hotel and await further instructions from the detectives.

The bogus doctor had by now changed his name to Charles Thompson and taken a job as physician on a ship due to set sail for Brazil. News reports later claimed that the police called for Dr Jean Barber just an hour after her arrival, but this is perhaps a little melodramatic – in her own account to the British Medical Association, Dr Barber said she arrived on a Friday and met the police the next Monday.

When the detectives pointed out their suspect, Dr Barber confirmed that she had never seen him before. She had also brought samples of her husband’s handwriting to show that it was not the same as the impostor’s. He was arrested before he could board the ship and the whole party set off for London, where he would be committed for trial. But there was a lot more excitement to come.

The prisoner, Harry Virtue, had gone by various names over the years. Born near Manchester in 1865, he had practised veterinary surgery in the US in the 1890s, but got into trouble for failing to pay bills and for regular thefts of veterinary instruments, books and even a horse and buggy. Having briefly known Dr Richard Barber, he took advantage of his acquaintance’s death as means of carrying on a medical career in England.

‘This alleged Dr Barber was a smooth villain,’ The Evening News (Roseburg, OR) would later report. ‘Much of his practice showed him to be a mountebank, and he was illiterate – he was in no sense like the gentleman whose name he had stolen.’

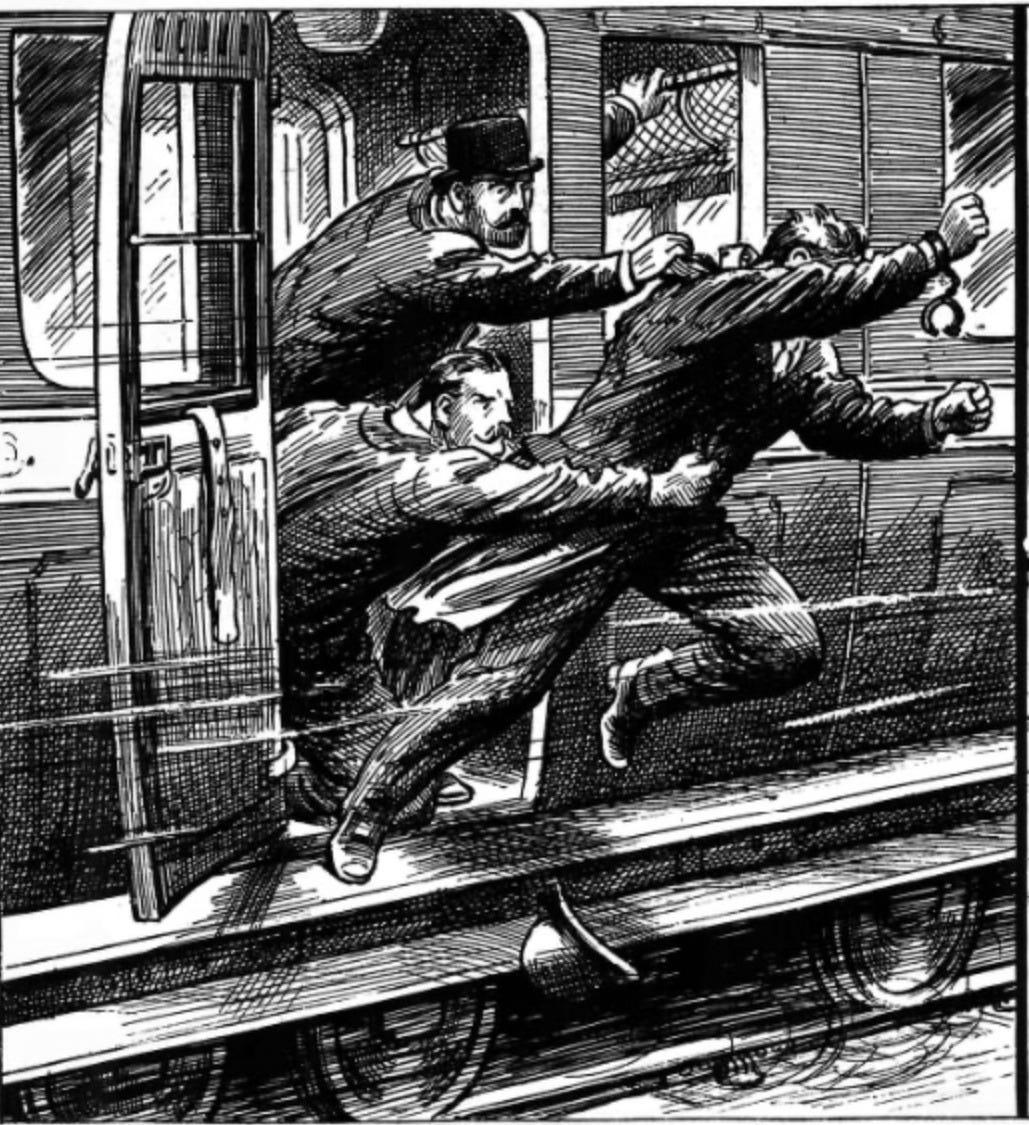

With Jean Barber in one railway compartment and the detectives with their prisoner in another, the team set off for Scotland Yard. Or, at least, that was the plan. The impostor himself was thinking more along the lines of a desperate struggle followed by either freedom or death.

They were three quarters of the way to London when Virtue asked to use the lavatory. Detective Sergeant McCoy released his handcuffs and accompanied him. On their return to the carriage Virtue noticed an open window.

‘That’s a good breather,’ he said, as McCoy began to readjust the handcuffs. ‘Let me put my head through the window for a moment.’ Before the detectives could reply, Virtue had dashed across the compartment, wrenched open the door and launched himself out. One of the officers would later testify in court:

All the time the prisoner kept on the footboard, and sometimes with one foot off the board and the whole of his body thrust forward he tried by sheer weight to detach himself from our grasp.

Eventually he secured such a position that it was impossible for us, handicapped as we were and fatigued by a struggle in which we were unequally situated, to continue any longer, and as there was no possibility of getting him back into the compartment, we decided that the next best thing was to lower him on the permanent way as far as possible, and so minimise the danger …

We managed to get his legs within a few inches of the ground, when his coat collar yielded to the weight of his body, and he dropped, leaving the collar in our hands.

So it was that the now collarless Virtue found himself prostrate next to the railway track near Leighton Buzzard. Injured but mobile, he made his way to a signal box, where he stole a hat and proceeded to a farmhouse, keeping his remaining handcuff well hidden as he told the occupants that he had accidentally fallen from a train. The farmer took him into Leighton Buzzard to get help for his injuries, but by then the train had halted, bloodhounds were baying along Virtue’s trail, and the alarm was spreading via telegraph and phone. The physician patching up Virtue’s wounds got the message and managed to detain him until the detectives arrived.

After his re-arrest, Virtue’s erratic behaviour resulted in admission to Banstead Asylum, but after six weeks, the doctors concluded he was feigning lunacy. In the magistrates’ court on 7 January 1913, he wrote down ‘I have lost my speech’ and did not participate in the proceedings.

Dr Jean Barber did not attend the subsequent trial at the Old Bailey. After spending some time visiting friends around the country and sorting things out with the Medical Register, she had returned to Oregon – and to an audience excited to hear her account of the adventure – in December 1912.

Virtue got nine months in prison, but this did not teach him the error of his ways. On his release, he moved back to Liverpool, ‘changed his appearance considerably’, knocked ten years off his age and began calling himself Harry Virtue Siddons. He recommenced posing as a doctor, got married, and even gained an appointment with the Birkenhead Military Medical Board, where he was responsible for assessing recruits as medically fit or unfit to serve. He claimed to hold the rank of Captain, and allegedly took bribes of money and whisky to give recruits the medical category they wanted.

Virtue/Siddons’ fraudulent activities came to light again in 1917 and he was arrested on several charges, including obtaining by false pretences £393 10s from the Paymaster of HM Forces and forging certificates for the notification of tuberculosis. Bail was initially refused after the counsel for the prosecution objected due to the danger of Virtue taking his own life, but the prisoner successfully appealed.

The counsel’s concerns proved prescient. On 29 October 1917 – the eve of his trial at Liverpool Assizes – Virtue was found very ill at his home in Canning Street, having taken an overdose of narcotics. Later that day, he used a surgical scalpel to cut his own throat, dying of his injuries.