Nellie Bly in the mad-house

Nellie Bly's investigative journalism revealed the shocking truth about the treatment of women deemed insane.

Once you arrived on Blackwell’s Island, no one was coming to save you.

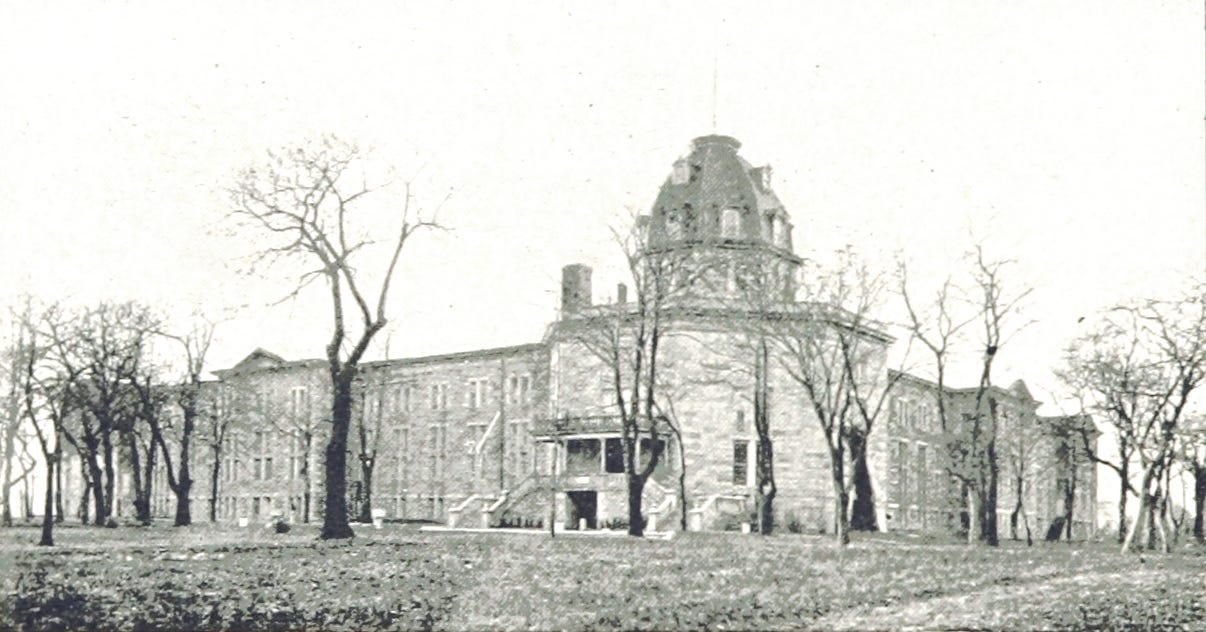

The lunatic asylum on the East River, New York City, was a dustbin for troubled and troublesome women. Some suffered with psychiatric illness, some had learning disabilities, and some had simply proved inconvenient to their families or employers. In this dreaded institution, every form of behaviour was considered proof of insanity, and inmates could do nothing but try to survive the filthy conditions, lack of food and the violence of abusive nurses.

In 1887, Nellie Bly – the pen name of Elizabeth Cochrane (1864-1922) – undertook to expose the cruelty meted out to the women incarcerated on Blackwell’s Island. Her legendary undercover assignment not only forced the authorities to overhaul the treatment of the mentally ill, but also ignited the rise of investigative journalism and the opportunities it brought for female reporters to go undercover.

Bly began her career at the Pittsburgh Dispatch and set out to investigate factory working conditions – but factory owners complained to the paper and she was moved to the fashion and society pages, which were considered more appropriate for a woman writer. She travelled to Mexico to write about the culture, but criticised the regime’s imprisonment of a journalist and had to flee the country. She moved to New York and joined The World newspaper, published by Joseph Pulitzer (of prize fame).

It was Pulitzer who challenged her to pull off the daring assignment of experiencing the asylum first hand. People could visit, but with staff on their best behaviour and the inmates’ accommodation out of bounds, visitors did not get to see the reality of life there. Nellie Bly would have to get herself admitted as a patient, and trust that The World would send someone to get her out. Her findings – published first as a series of articles and then as a book titled Ten Days in a Mad-House – forced the public and the authorities to confront uncomfortable truths about the treatment of those considered insane.

Bly’s mission began at the Temporary Home for Females – a cheap lodging house for working women – where she acted strangely. Giving her name as Nellie Brown, she claimed she could not remember much about her life but had lost her luggage and needed somewhere to stay. She began making odd comments about the other residents being crazy, and sat up all night refusing to sleep.

At first making fun of her, the other women became scared that she might kill them – with the exception of one Ruth Caine, whose kindness was a beacon of warmth in what would have been an isolating situation for a genuinely troubled woman. The lodging-house keeper had Bly removed by the police and, after a short court hearing and little attempt to look for any family or friends, she was sent to Bellevue Hospital for examination. The doctors there were satisfied that she was insane, and committed her to the Women’s Lunatic Asylum.

During the next ten days, Bly witnessed scenes of unimaginable suffering and neglect. Patients languished in overcrowded wards that reeked of dirt and despair. Those considered violent were sent to the ‘rope gang’ where they were joined together by a rope attached to leather belts and forced to pull a heavy iron cart around the grounds. Others had to spend their days sitting in silence on uncomfortable benches.

An important part of Bly’s story is that from the moment she arrived in the asylum, she stopped feigning insanity and behaved as her normal self. As she would discover, this had no effect on the staff’s opinion that she was in the right place. She talked to other inmates and discovered that many were as sane as herself; they had been admitted for spurious reasons.

A French woman, Josephine Despreau, became ill one day at her lodgings and, like Bly, had been taken away by police at the landlady’s request. Because she didn’t speak much English, she could not understand the proceedings, and could not defend herself from being committed to the asylum.

‘When I first came,’ she said ‘I cried that I was here without hope of release, and for crying Miss Grady and her assistants choked me until they hurt my throat, for it has been sore ever since.’

Another inmate, Margaret, had been working as a cook and lost her rag with some fellow servants when they ruined her clean floor; this understandable anger was deemed evidence of insanity.

The squalid conditions and horrible food were accompanied by violence from the nurses. A patient called Mrs Cotter described being beaten with a broom handle and jumped on, causing internal injuries. The nurses had wrapped a sheet tightly round her head and plunged her into a cold bath.

‘They held me under until I gave up every hope and became senseless. At other times they took hold of my ears and beat my head on the floor and against the wall. Then they pulled my hair out by the roots, so that it will never grow in again.’

The physical abuse was blatant, but just as discomfiting to read are Bly’s accounts of the psychological cruelty displayed by the nurses, who kept watch for the arrival of any senior members of staff and moderated their behaviour accordingly. When no one was looking, they targeted the inmates’ personal weaknesses – a vulnerable woman called Urena Little-Page, who had a fixation about being 18 years old, received taunts that she was really 33. Another inmate, Sarah Fishbaum, had been placed in the asylum after being accused of infidelity, and the nurses tried to prompt her to make advances to the visiting doctors. An elderly blind woman was left to bump into furniture while the nurses laughed.

After ten days, The World sent a lawyer to inform the asylum authorities that he had found family members willing to take care of ‘Nellie Brown.’ She was released shortly afterwards and, while relieved at her freedom, experienced the guilt and sadness of leaving behind those who were not so fortunate.

The impact of Bly’s Ten Days in a Mad-house series was swift and profound. A Grand Jury investigation into the conditions at Blackwell's Island met with attempts at a cover-up, as asylum officials got wind of their visit and cleaned the place up. However, the jury believed Nellie Bly’s testimony and allocated public funds to the improvement of treatment for the insane, including greater oversight of institutional practices.

Another enduring legacy of Bly's madhouse assignment was its testament to the power of investigative journalism to effect real change. In an era when women were often relegated to the sidelines of public discourse, Bly fearlessly pursued truth and advocated for those whom society had failed.

New on the to-read shelf

Rites of Passage: Death and Mourning in Victorian Britain by Judith Flanders

In Rites of Passage, acclaimed historian Judith Flanders deconstructs the intricate, fascinating, and occasionally – to modern eyes – bizarre customs that grew up around death and mourning in Victorian Britain.

Through stories from the sickbed to the deathbed, from the correct way to grieve and to give comfort to those grieving to funerals and burials and the reaction of those left behind, Flanders illuminates how living in nineteenth-century Britain was, in so many ways, dictated by dying.

This is an engrossing, deeply researched and, at times, chilling social history of a period plagued by infant death, poverty, disease, and unprecedented change. In elegant, often witty prose, Flanders brings the Victorian way of death vividly to life.

HistMed Highlights

MEDICAL PIONEERS: 🔬🧬 A guided walk around Willesden Jewish Cemetery reveals the fascinating lives of talented men and women who made invaluable contributions to biology, chemistry, psychology, nutrition, mechanics, agriculture, engineering and medicine, as well as the promotion and dissemination of scientific knowledge around the world. 13 March 2024, 11am GMT, £10.

DRACULA AND DISEASE: 🧛🩸‘The blood is the life!’ repeats Renfield in his Victorian asylum. Dracula may be literature’s most famous blood sucker, but his creator, Bram Stoker, came from a medical family, and knowledge of the medical practices of the time infuse Stoker’s novel. This online talk by human remains conservator Cat Irving will explore the diseases that have fed into vampire mythology and the medical history that Stoker was drawing on for his creation. 16 March 2024, 10am GMT, free but book a ticket.

STORIES FROM THE HIGH SEAS: ⚓ 🚢 During the Easter holidays, the Thackray Museum in Leeds presents Shipshape: Medicine at Sea. From galleons and battleships to trawlers and cruise liners, which worrying ailments have made sailors, captains and pirates alike gruesomely groggy? And what could be prescribed to ensure you don’t fall victim too? There’ll be a treasure trove of activities for all ages. 23 March - 14 April 2024. Usual museum admission applies.

AFTER LOVE: ❤️🩹🥹A new interdisciplinary project led by Dr Sally Holloway approaches romantic heartbreak as a distinctive form of extreme grief with profound effects on the body and mind. Through analysing heartbreak as an embodied emotional experience, it aims to ascertain how its distinguishing characteristics have changed over time, and how we can most effectively process and heal from it. The project’s website is now live.

What an amazing story! Very interesting post, thanks.