New blood for the scalp

In the first decade of the 20th century, vacuum caps raised the hope of raising hair on bald heads.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Do you have an exceptionally active brain? It might be using up the blood supply that would otherwise nourish your scalp, leaving you in danger of going bald.

This was one prevalent – and rather self-congratulatory – explanation for hair loss at the beginning of the 20th century. Other theories blamed microbes or washing the head too often in cold water, and a jokey stereotype held that a bald pate was the consequence of being a womaniser.

In 1909, surgeon J O Cobb of the US Public Health and Marine Hospital Service asserted that none of this was true – baldness resulted from wearing a tight hat. Although hair loss had always happened, and was only to be expected in older gents, it was becoming more prevalent in younger men. This could cause annoyance and distress, because:

…the moment their baldness is discovered their friends begin to slap them on the back, and nudge and wink and point the accusing finger at this early sign of their overtasted forbidden fruits. A young man thus afflicted springs into prominence at once as a person who is more or less of a rake, and everyone takes delight in poking fun at him, especially if he is a doctor.1

Dr Cobb (of whom I have not seen a picture but in whose words I detect bitter experience) blamed hats. Particularly guilty was the fashion for straw boaters, which were inclined to blow away and caused wearers to force them down too hard onto their heads. ‘Gentlemen who ride much in automobiles,’ were prone to baldness because only a tight hat would stay on when speeding down the road. Cobb recommended going hatless wherever possible, and massaging the scalp every night.

While debate continued about the reasons for hair loss, inventors were working on solutions. As well as the various restorative lotions and medicines, a market developed for follicle-stimulating vacuum caps, which promised to get the blood pumping and the hair flowing.

Claude A O Rosell of New York City patented a simple device in 1899. His rubber cap, which he dubbed the ‘Capillary Chalice’, took its inspiration from the ancient surgical practice of cupping. By using suction to draw blood into the scalp, the cap was intended to invigorate the circulation, loosen the scalp from the skull and even form new blood vessels. To make sure it created a seal and didn’t ping off, one could use beeswax, cold cream, petroleum or other ointment around the perimeter.

Just a year later, Frederick Watkins Evans of St Louis introduced a more advanced version, which would go on to be widely advertised on both sides of the Atlantic. This consisted of a frame that sat above the scalp, with an airtight band around the head and a tube leading from the back. A vacuum could be created by sucking on the tube.

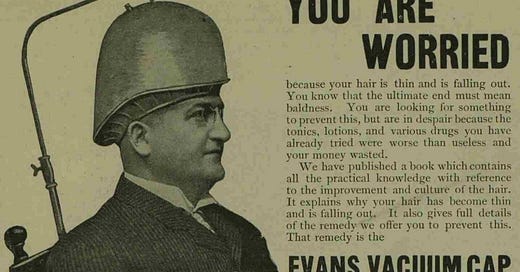

Napoleon W Dible (who sported a luxuriant head of hair himself) invented another version of the vacuum cap in 1904 (patented 1906), but he wisely decided to go into property development instead, becoming one of Kansas City’s most prominent house builders. It was F W Evans who led the vacuum cap market, with illustrated advertisements that directly addressed the potential customer’s concerns:

You are worried because your hair is thin and is falling out. You know that the ultimate end must mean baldness. You are looking for something to prevent this, but are in despair because the tonics, lotions and various drugs you have already tried were worse than useless and your money wasted.2

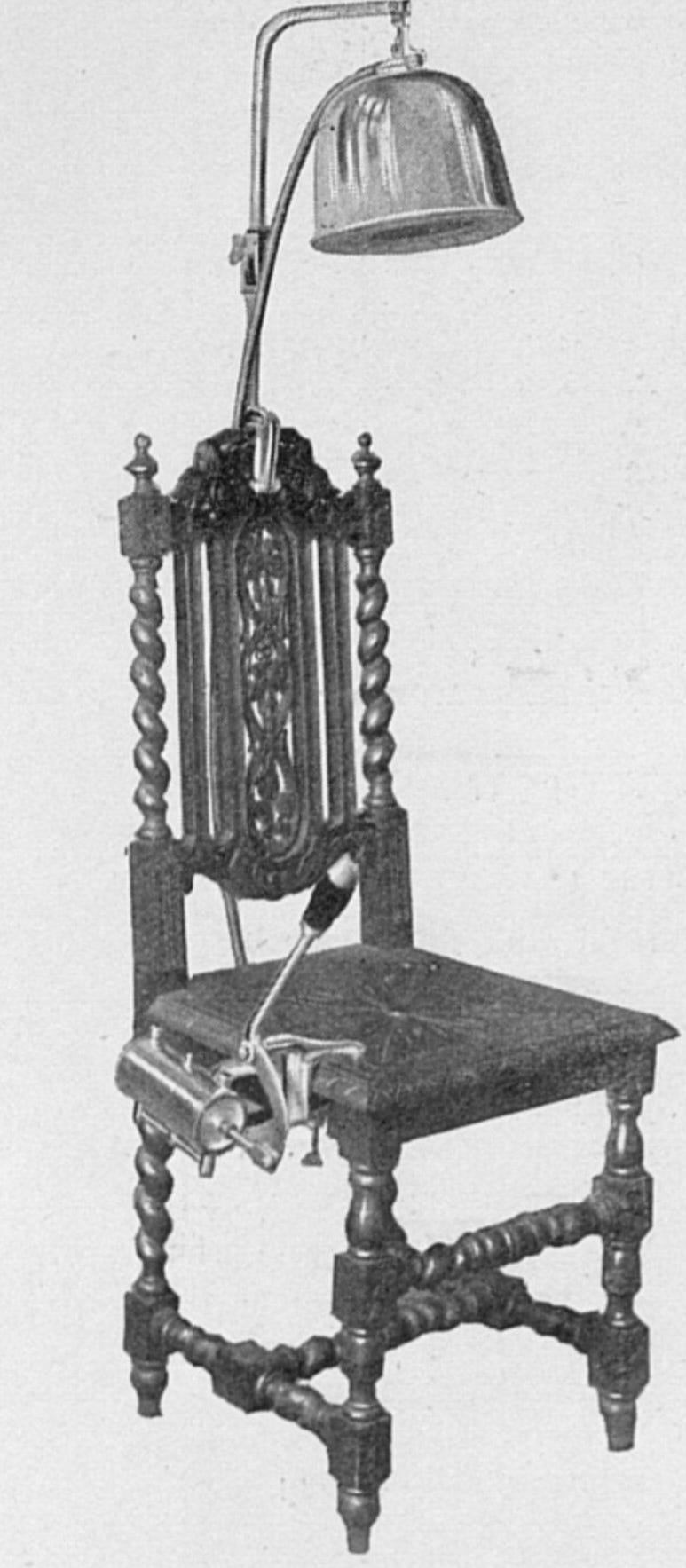

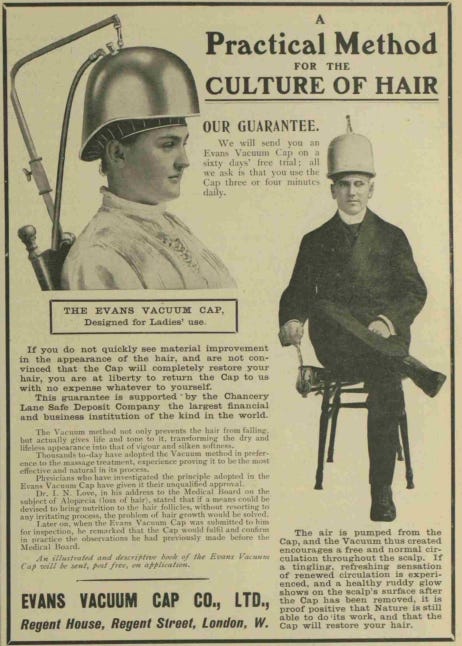

By this time, the mouth-operated suction tube from the patent had been replaced by a pump handle that attached to the seat of the user’s chair. Instructions advised using the cap for just three to four minutes a day, and claimed that the experience would be enjoyable:

The effects produced by the vacuum are pleasant and exhilarating. It gives the scalp a healthy glow, and produces a delightful tingling sensation, which denotes the presence of new life in the scalp, and which cannot be obtained by any other means.3

Although the devices targeted male pattern baldness, they did not neglect the female market. Some ads claimed that the device was ‘designed for ladies’ use’ - it would not just grow new hair but impart life and tone to existing barnets, ‘transforming the dry and lifeless appearance into that of vigour and silken softness.’4

In 1916, Dorothy Osborn of Ohio State University published a study that looked at patterns of baldness in 22 families. She concluded that a single gene was responsible for balding and that this was inherited as an autosomal dominant trait in males and as autosomal recessive in females. The choice of headgear was not to blame, and no device or potion could persuade the gene to start producing hair.

By then, vacuum caps were largely out of vogue anyway, and classified ad columns show people trying to offload second-hand (or second-head) ones that had presumably been set aside to grow their own thick pelt of dust.

J O Cobb, MD, ‘Baldness,’ The New York Medical Journal, 26 June 1909.

Illustrated London News, 24 November 1906.

The Bystander, 14 March 1906.

Illustrated London News, 26 May 1906.

More sources:

C A O Rosell, Device for Promoting Growth of Hair, Specification forming part of Letters Patent No. 624545, 9 May 1899.

Frederick Watkins Evans, Device for Promoting Growth of Hair, SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 655,481, 7 August 1900.

Napoleon W Dible, Apparatus for Promoting the Growth of Hair, Specification of Letters Patent No. 809360, Application filed 4 October 1904, patent granted 9 January 1906.

Dorothy Osborn, ‘Inheritance of Baldness,’ Journal of Heredity, August 1916.

What I find fascinating is the enduring quality of these myths.

The reason I say this is because I used to wear hats when I was in my teens and I remember the elders of my family (grandfather, grandmother, etc...) would say that I should be careful lest I wanted my hair to fall off.

I guess some myths fade away but are never completely erased from the collective consciousness!