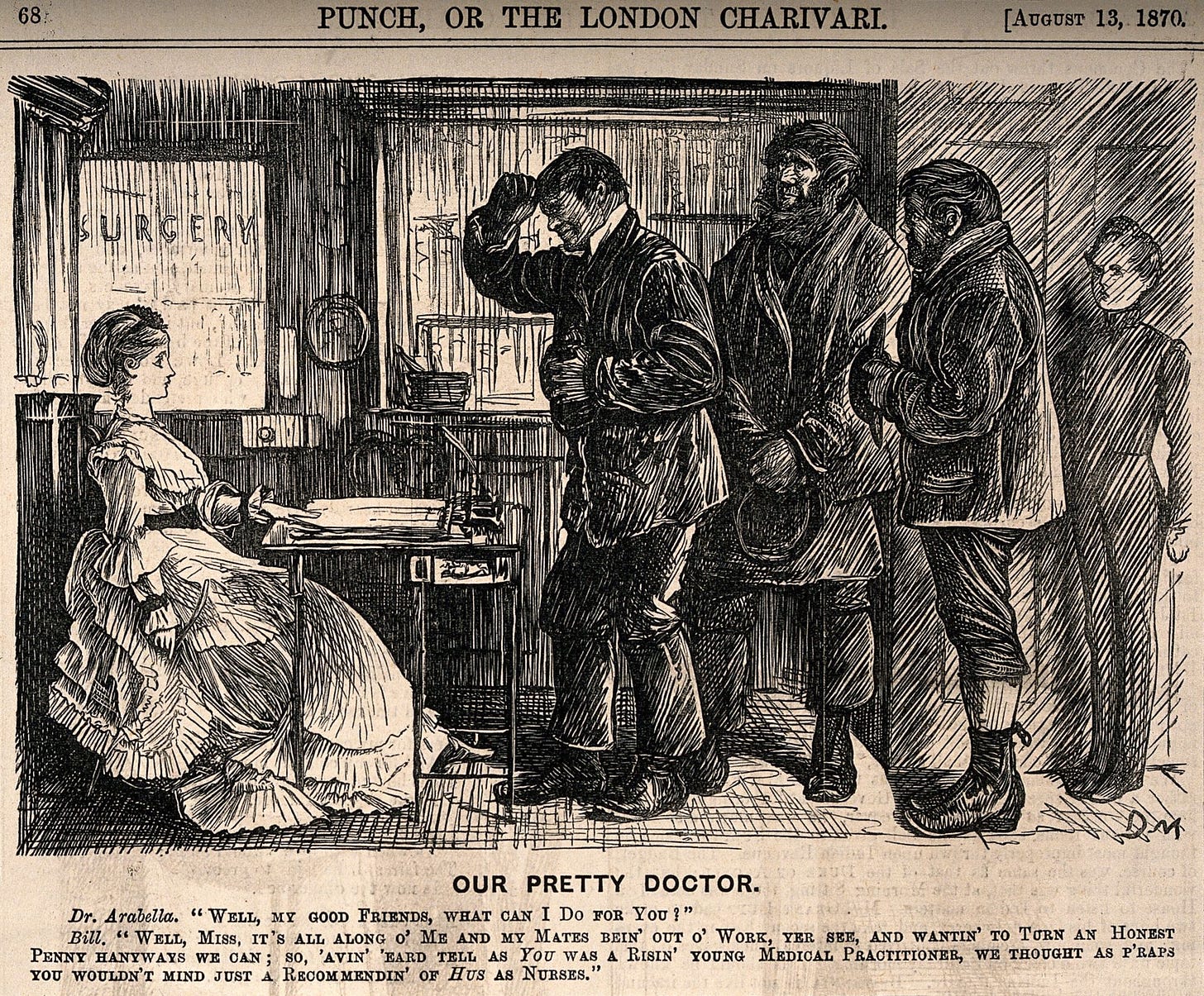

Petticoat physic: the opposition to Lady Doctors

The reasons why some 19th-century commentators objected to women's medical education.

Britain was a late adopter of medical education for women, and while the novelty of the ‘lady doctor’ received support from some elements of the medical profession and the public, there was also no shortage of opposition. Debate around this controverisial topic remained a regular feature of medical journals and lay publications throughout the second half of the 19th century.

Opinions varied – it was not a case of the male medical profession presenting a united front against female invaders. Even journals that were broadly against the inclusion of women – such as The Lancet – allowed room for contrasting views. Several common themes, however, emerged among those who voiced their disapproval.

One argument said that female doctors simply weren’t required – the profession was already well stocked with men, and women would displace some of these hard-working fellows, making them redundant. This would increase celibacy because men could not afford to get married, which meant more women in need of employment – a vicious cycle!

Although campaigners for women’s medical education argued that female patients would feel more comfortable with a doctor of their own sex, the opposing view held that this was not true.

‘We greatly doubt whether the women of England are at all prepared to be given over to the treatment of their medical sisters. Women hate one another, often at first sight, with a rancour of which men can form only a faint conception; and they have become accustomed to a certain tenderness in sickness, arising remotely from the different sex of the doctor, which they would surely and deeply miss under the proposed régime.’ (‘Medical Education for Women’, The Lancet, 7 May 1870.)

A supposition also abounded that women did not have the emotional, intellectual or physical robustness for such a demanding career. This view was not confined to male commentators – under the pseudonym 'Mater', an anonymous laywoman wrote to the Lancet in 1870. She expressed polite misgivings as to the appropriateness of a 'lady correspondent' daring to approach such a prestigious publication, and went on to criticise her own sex as entirely unfit to join the medical profession.

Her main point held that a woman doctor would lack strength of nerve and be unable to keep calm in a crisis. Even if she did appear to have the necessary focus and composure, these could not be relied upon owing to the 'constitutional variations of the female system.' Secondly, women could not keep secrets, so all and sundry would know the private details of the patient's case. Mater hinted at issues of 'modesty and delicacy' too, but felt such repugnance at discussing them that she would leave that to male campaigners.

We can surmise what these issues entailed from the British Medical Journal’s question: ‘Is it possible to give any definition of feminine delicacy which shall permit to young ladies, under any circumstances short of absolute necessity, the study of medical jurisprudence and the perusal of Mr Acton’s books?’ (‘The Admission of Ladies to the Profession’, BMJ, 7 May 1870.)

William Acton was the author of The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs (1862), as well as works on prostitution, venereal disease and masturbation. He famously wrote: ‘The majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled with sexual feeling of any kind.’ Should women become doctors, they would have to study such insalubrious subjects, not to mention the impropriety of dealing with male patients’ private disorders.

Women were supposed to want to get married, which brought further concerns to the debate. Would women doctors have to be 'vowed vestals', Mater wondered, or would such things not be an issue because no man would want them anyway? What would happen if they did marry? They would presumably neglect the household and fail to create a restful environment for their husbands, and worse:

Is a ‘nursing mother’ to suckle her babe in the intervals snatched from an extensive practice? Or is the husband of ‘the qualified practitioner’ to stay at home and bring up the little one with one of those ‘artificial breasts’ so kindly invented to save idle and selfish women from fulfilling the sweetest and most healthful of the duties of maternity? (‘A Lady on Lady Doctors’, The Lancet, 7 May 1870.)

The Lancet had published a similar view back in 1858:

‘Continuous and regular attendance to daily duties are absolutely required from every conscientious person undertaking the care of the sick. With women this is impossible.’

A pregnant woman was:

‘… not fit to be entrusted with the life of a fellow creature, nor is it well for herself or the child yet unborn, that she be exposed to the revolting scenes which a medical man has to brave.’ (‘Petticoat Physic’, The Lancet, 9 January 1858.)

The Saturday Review (30 April 1864) mused that as married women doctors would no doubt ‘leave off doctoring and stick to ordering dinners and watching the babies’, it was not worth their while to qualify. The paper did concede, however, that ‘an old maid who is a lady-doctor has a better chance of happiness than an old maid who is not a lady-doctor,’ and that the profession might therefore be an option for ‘a plain girl with ability enough.’

A more frivolous contribution to the debate came from the serio-comic journal Judy (22 January 1879), which published a dialogue showing a female doctor prescribing a new bonnet, velvet coat, silk dresses and jewellery to banish her patient’s low spirits.

In 1874, the London School of Medicine for Women opened, and two years later the Medical Act provided for all medical schools to accept female students. It did not, however, force them to do so and women continued to meet with both hostility and ridicule as they began to make inroads into the profession.

Best Medicine

Tuesdays at 6.30pm on BBC Radio 4, BBC Sounds and wherever you get your podcasts.

Begins Tuesday 3 October. I’ll be appearing on the show on 14 November!

Best Medicine is your weekly dose of laughter, hope and incredible medicine. Award-winning comedian Kiri Pritchard-McLean is joined by funny and fascinating comedians, doctors, scientists, and historians to celebrate medicine’s inspiring past, present and future.

Each week Kiri challenges her guests to make a case for what they think is 'the best medicine', and each of them champions anything from world-changing science, an obscure invention, an every-day treatment, an uplifting worldview, an unsung hero or a futuristic cure.

Whether it’s micro-robotic surgery, virtual reality syringes, Victorian clockwork saws, more than a few ingenious cures for cancer, world-first lifesaving heart operations, epidurals, therapy, dancing, faith or laughter - it’s always something worth celebrating.

Snake Oil!

Snake Oil: The Golden Age of Quackery in Britain and America. I’m visiting Bedford Skeptics to speak about the history of patent medicines. 19 October 2023, 7.30pm, The North End Social Club, Bedford MK41 7TW. All welcome - just turn up!

Featured events

30 September 2023: Conversations about Death. The Wellcome Collection’s visitor experience team will lead this small-group discussion event about the end of life and the legacy we leave for our loved ones. 11am, Wellcome Kitchen, London NW1 2BE.

3 October 2023: The Body Farm: What the Bones Reveal. In this Smithsonian online presentation, Forensic Anthropology Center Director, Dawnie Wolfe Steadman, reveals how research into decomposition can help bring murderers to justice. 6.30pm ET. Tickets $25 for non-members.

4 October 2023: Witchcraft: A History in 13 Trials. Author Marion Gibson discusses her new book about witchcraft’s murky and violent history, focusing on the stories of accused women. 7.30pm, an online talk from The National Archives - book in advance and pay what you can.

11 October 2023: Marcus the Medicus: Roman Battlefield Medicine. Re-enactor Andrew Newton will be at Inverness Museum and Art Gallery, IV2 3EB, from 11am - 4pm, giving visitors a chance to find out more about Roman medicine and see some replica surgical tools. Free - just drop in.