Profiting by deceit: a treatment for alcoholism in Edwardian London

Businessman Arthur Lewis Pointing introduced 'Antidipso', a product that gave false hope to the families of alcoholics.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

'ARE YOU LITTLE?' asked the advertisements promoting 'A. D. Invisible Elevators' from the Oriental Toilet Company. For 3s 9d, the elevators promised to increase anyone's height by up to four inches. They were the latest in a succession of dubious businesses promoted by Arthur Lewis Pointing (1867-1910).

In the three months leading up to August 1897, Pointing made about £600 from sales of the Invisible Elevators. Customers, however, complained that they were still as short as ever, prompting Inspector Leach of the Met to have a quiet word.

When Pointing was arrested for fraud, the mundane truth about the elevators rose to public view – they were just heel raisers to put in one’s boots. At his hearing at Bow Street Police Court and subsequent Old Bailey trial, annoyed purchasers came forward to relate their experiences.

Frederick Dry, an india-rubber worker and amateur actor from Manchester, had been sceptical, but wanted to look taller on stage. He said:

I got two pieces of cork, which I put in my boots, following the directions—they appeared to increase my height about one-eighth of an inch—I kept them there for about sixty minutes—they threw my body forward, and gave me a pain in the back, and cramped my toes—I took them out.

The judge ruled that The Oriental Toilet Company was a genuine business and a few dissatisfied customers didn't warrant a conviction. Arthur Pointing was free, but the chances of anyone buying his Invisible Elevators had now shrunk. It was time to leave Oriental opportunities behind and go West. He set sail across the Atlantic to join the Klondike stampede.

Like most prospectors, he did not strike gold – at least, not in the way he expected. While travelling across the US, however, he could not help but notice the money to be made in the patent medicine trade, and an addiction treatment called Dr Haines's Golden Specific caught his eye.

Products like the Golden Specific filled American newspaper advertising columns with promises of miraculous cures. Pointing wrote off for these remedies and, instead of bemoaning the resulting flood of junk mail, carefully filed it away. He returned to London with a plan to replicate it, and within just a few years had at least eight business concerns on the go. It is possible that his almost manic energy was an early sign of the disease that would ultimately lead to his death.

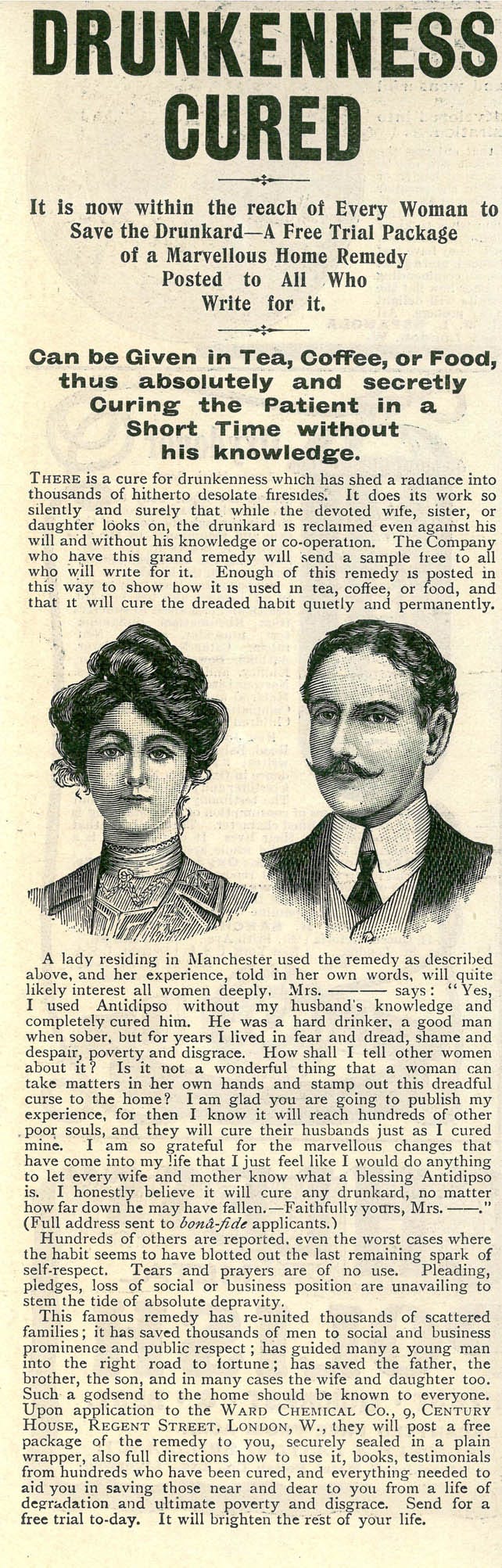

The most prominent of his products was also the most morally disconcerting. ‘Antidipso’, inspired by Dr Haines’s Golden Specific, claimed to cure the most unregenerate drunkard. Said to be a natural remedy derived from little-known South American herbs, it had ‘shed its radiance into thousands of hitherto desolate homes,’ and claimed to have ‘guided many a young man to sobriety and into the high road of fortune’.

The number of unregenerate drunkards prepared to send off for a remedy was, of course, limited, so Antidipso targeted a more lucrative market – the drinker’s loved ones. Enticing enquirers with a booklet called Bright Beams of Hope, Pointing – trading as The Ward Chemical Company – promised an end to day after day of lies, debt, and vomit in the carpet.

There need be no confrontation, no violence, no broken promises – a powder in the drinker's coffee would do the job in secret. The unsuspecting patient would be restored to the wholesome and sober bosom of his family and would once again achieve business success and social acceptance. The patient was almost always presented as male – but responsibility for his behaviour was assigned to women.

Testimonials told of wives who ‘lived in fear and dread, shame and despair, poverty and disgrace,’ using Antidipso to regain the pleasant and hard-working men they thought they had married. The wife must ‘take the matter into her own hands’ and adopt the role of guardian angel to an infantilised abdicator of responsibility – it was up to her to change him, and any failure would be her fault.

In 1904, representatives of the British Medical Journal replied to an Antidipso advertisement to see what would happen. They received a copy of Bright Beams of Hope, and once on the mailing list, could not escape the Ward Chemical Company’s persistent letters with special offers.

The surreptitious nature of the treatment was not just marketing hyperbole – the product itself was designed for concealment. When the British Medical Association acquired a packet for analysis, they discovered that the powders came in two colours – the purchaser could choose the most appropriate one depending on the colour of the food or drink to be laced.

The Lancet noted the lack of patient consent with disgust, asserting:

There have been many cruel and wicked frauds committed by the sellers of quack medicines but of all that have come to our notice we do not know one of a baser character than that which is perpetrated by the proprietor of Antidipso.

Their analysis showed the product to comprise 78.22% milk sugar and 21.78% potassium bromide. Although the bromide might have caused nausea and vomiting, putting the patient off alcohol for a while, the Lancet concluded that the tiny quantities in the daily dose of Antidipso would not make any difference. Even a placebo response was impossible since the patient was unaware he was under treatment.

One packet of Antidipso, retailing at 10s, contained ingredients to the value of about 1 ½d. But however much money this venture made for Pointing, it was not enough to save him from the bacteria that had colonised his brain. It is impossible to say at what point in his eventful career Pointing contracted syphilis, but the devastating tertiary stage of the disease took hold at the height of his success.

In October 1905, he fell ill in the street. Within a few days, he was back in action at The Ward Chemical Company, but his recovery was only temporary. He showed signs of general paralysis of the insane, a neurological condition resulting from syphilitic infection and resembling severe psychiatric symptoms.

On 26 July 1906, Pointing’s health broke down irretrievably and he was taken to Peckham House Asylum. No records survive of his four-year stay there, but in common with other GPI patients he would have experienced delusions, progressive dementia, seizures and loss of muscular function, ending up paralysed and doubly incontinent. This living death became a merciful one on 14 April 1910. Pointing was 42 years old and left a fortune of £37,909 2s 6d, some of which he specified should go to his employees and some to charity.

If the Lancet were capable of influencing people’s fate, it might be said to have done so when it opined of Antidipso’s proprietor: 'To raise false hopes in those whose lot it is to be tied to a drunkard is disgraceful and no punishment can be too bad for the person who profits by such deceit'.

Brilliant. Similar products still on the market today! I know, my brother has tried them all and he's still drunk.