Scattering diamonds: mercury and the pox

Eighteenth-century surgeon Daniel Turner related the horrors - and embarrassments - of treatment for syphilis

‘A Gentleman that for some Years past, had led but a loose Life, finding some pressing Symptoms, whereby he was now disabled from following his accustom’d Liberties, advised with me.’

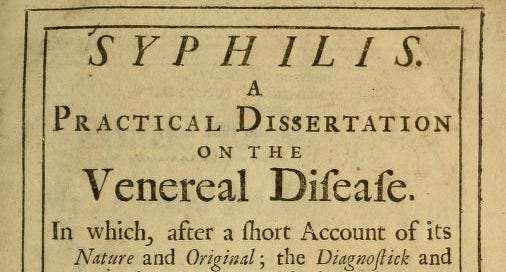

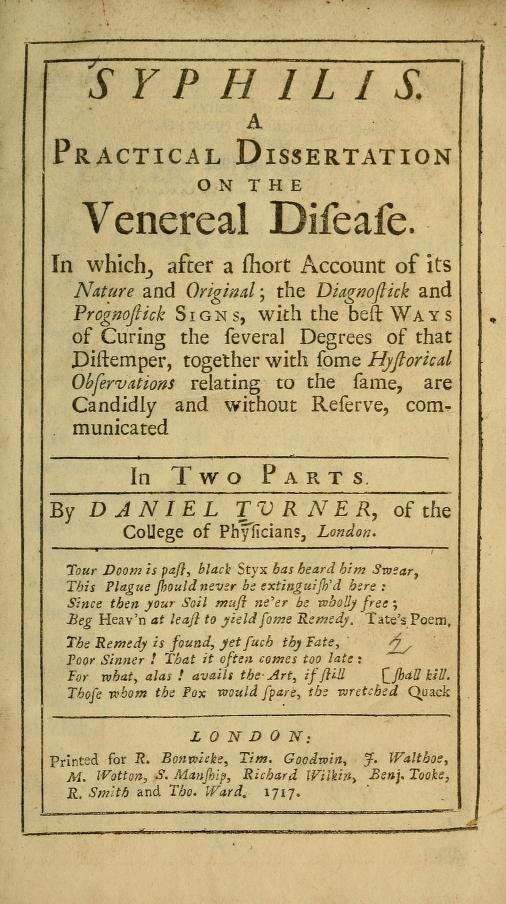

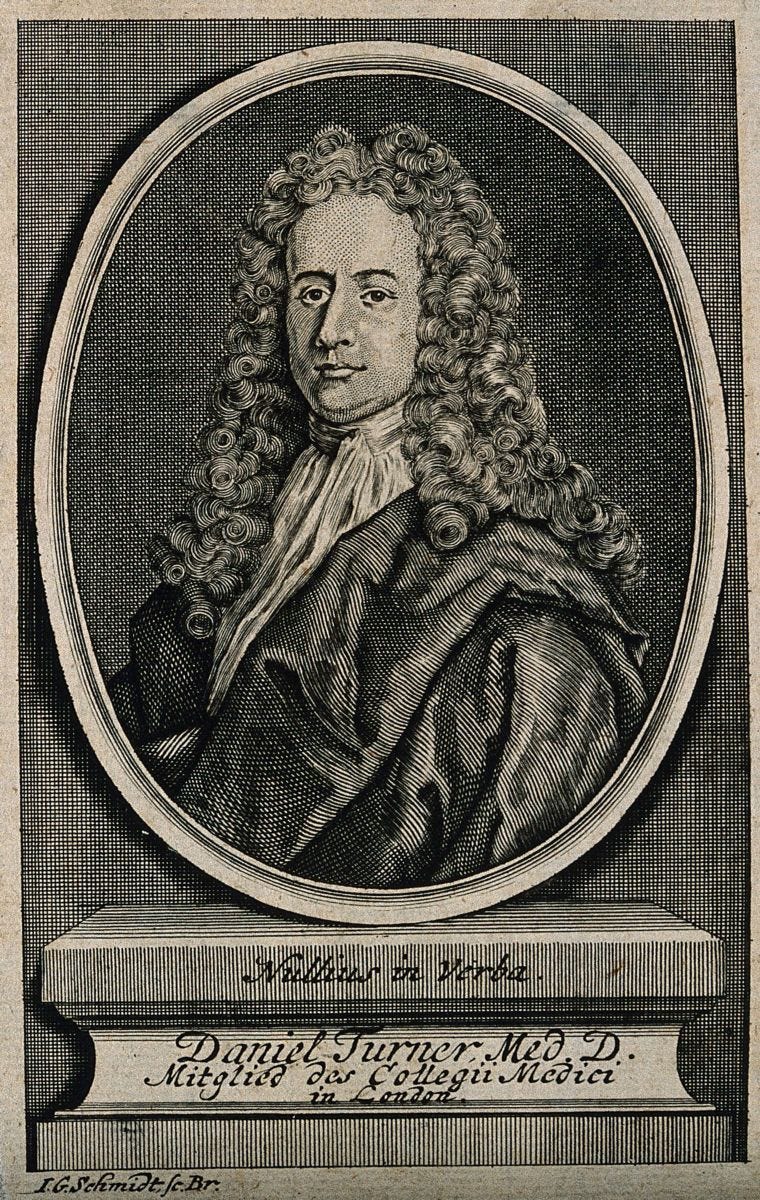

The surgeon Daniel Turner (1667–1741) included 20 case histories in his 1717 work Syphilis: A Practical Dissertation on the Venereal Disease. The patients are anonymous, but details of their lives and suffering give an insight into the devastating impact of a disease that was, despite the best efforts of surgeons like Turner, incurable.

Some are young men dragged along by their worried mothers to seek help; others have shopped around different practitioners and treatments for months. There is the ‘off-cast Mistress to a Person of Condition’, a couple who have become too ill to make their regular business trips to Flanders, and an ‘unfortunate tradesman’ whose skull has been slowly rotting for 15 years. Although Turner is by no means a sentimental writer – he frequently describes negotiating his fee before he will treat someone – the pain, fear and bewilderment of his patients makes for tragic reading.

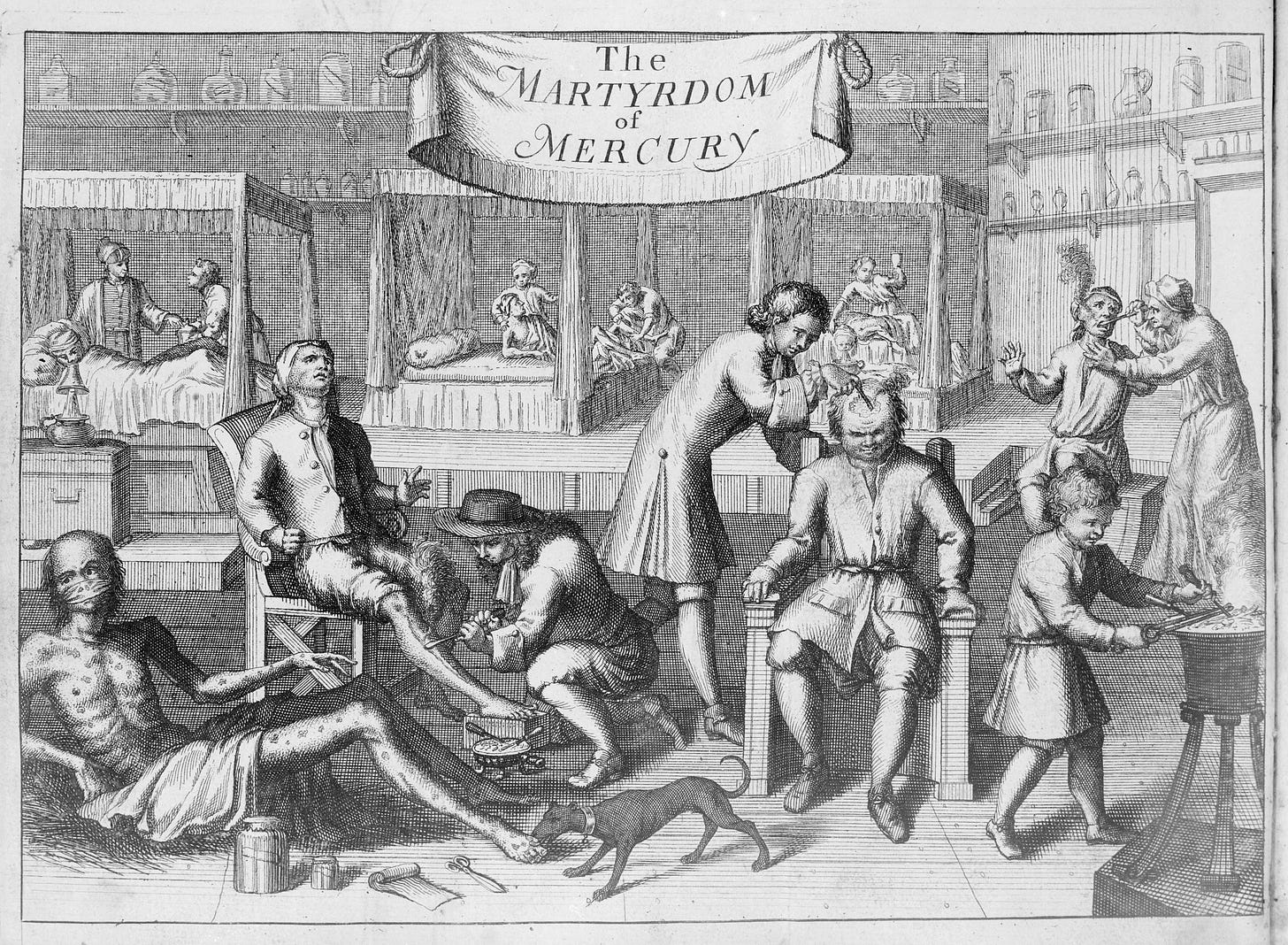

The treatment favoured by Turner and most (though not all) other practitioners of his time was to put the patient into ‘a salivation’ – administering mercury until the toxicity caused the overproduction of saliva and the ‘venereal venom’ was flushed out of the system. As syphilis has latent phases where symptoms diminish, the treatment often appeared to work.

There were three standard ways of administering mercury – giving it as an internal medicine, rubbing it on the skin or surrounding the patient with fumes.

In preparation for salivation, Turner advised that the patient should undergo purging medicines or bloodletting and a warm bath. Women should have the treatment just after menstruation, and the temperate seasons of late spring and early autumn were the best time to carry it out – though of course it was not always possible to wait for the perfect time of year.

Turner did not agree with the common practice of using large doses of crude mercury as an internal medicine – instead, he recommended 15 grains (about a gram) of calomel (mercurous chloride) twice a day. Although ostensibly gentler, this still had dramatic effects for the unhappy patient.

Initially the sufferer could expect violent diarrhoea and ‘horrid torture of the bowels,’ which in some cases would be quite sufficient to get rid of both disease and patient permanently, but after a few days came the signs of ptyalism – the copious production of saliva from which the treatment gets its name:

‘…the Tongue looks white and foul, the Gums also stand out, the Breath stinks, (which is a good Omen of its coming on) and in general the whole Inside of the Mouth appears shining, seems as it were parboiled, lying in Furrows, much after the manner as it does in those who have lately held strong Spirits therein for the Tooth-ach.’

The patient would need to continue the treatment for at least three weeks, which meant it was difficult to hide the nature of the illness from disapproving acquaintances. Those whose symptoms were mild might try to continue with their normal activities, but this was not always a good idea.

One reason Turner avoided crude mercury was that it could exit the other end of the digestive system at inappropriate moments. In another of his works, The antient physician's legacy impartially survey'd: With a discourse on quicksilver, as now commonly taken (1734), he relates the story of a lady who was dancing at an assembly when she ‘happened to let go some particles of the Quicksilver she had taken in the morning’. People scrabbled to pick them up, thinking she had ‘scattered her diamonds’, leading to widespread amusement and embarrassment.

Turner had also once noticed some globules of mercury on a tavern floor, and learnt from the barman that two gentlemen were in the habit of bringing a bottle of quicksilver to dose from every morning before having a smoke and a gill of wine. The barman speculated that the mercury droplets came from these bottles; Turner ‘rather believed from their Backsides’.

Turner’s preferred method of treating syphilitic sores in the mouth and nose was the cinnabarine fumigation. Cinnabar is a bright red form of mercury (II) sulphide that, when burnt, produces a potentially lethal vapour.

The patient had to sit on a chair underneath a large blanket suspended from the ceiling. He or she would hold an earthen platter on which was a hot brick and a quantity of finely powdered cinnabar. The patient must then breathe in the fumes, and was provided with a pot to spit in should any phlegm arise. This procedure was to be repeated morning and night for about a week. Ideally, the patient should stay indoors during this period, but Turner found that busy types tended to ignore this advice and go about their lives – the fact that this was possible made the fumigation treatment more popular than a long and miserable course of calomel.

A ‘stubborn and rebellious’ pox would also require ‘unctions’ – mercurial ointment rubbed onto the skin, the patient then being wrapped up in layers of flannel clothing. Turner found crude mercury acceptable for this but he was against the common practice of rubbing the ointment all over the body and preferred to limit it to the legs and arms. The patient would usually do this themselves but in the case of someone very ill, the surgeon would have to undertake this risky procedure, and Turner describes using bladders over his hands as an early form of surgical glove. As unpleasant side effects arose, the patient could expect to receive aggressive treatment for these too, so they could end up enduring bloodletting, emetics and laxatives on top of the mercury treatment. It is safe to say this was not fun.

According to Daniel Turner, most of his cases received benefit from these ordeals – he tended to believe that those who got worse or died must have been consulting other surgeons or quacks.

As for the libertine gentleman we met at the beginning, he underwent a 25-day course of calomel boluses, which caused his tongue to swell so much that he could not speak. Thanks to the care of an unnamed but clearly diligent and experienced nurse, he made it through and became well enough to ‘return to his folly in pursuit of the same Pleasures’ – until next time, when he told Turner that he would sooner die than undergo the treatment again.

I have another project on the go at the moment – a podcast called She Wrote Too with my pal Nicola Morgan. In each episode, we focus on a lesser-known work of literature from female writers of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Our first episode is out now, so if you would like to have a listen and subscribe to receive the next one, visit shewrotetoo.substack.com.

The Society of Genealogists’ Sick London online course is now in progress and you can sign up to any or all of these weekly workshops. Coming up on 18 September, Suzie Grogan discusses Surgeon-apothecaries: Frontline Medicine in the early 19th century and on 25 September, Judy Hill looks at Victorian Pharmacies and The Diet of the Poor.

On 21 September at 2pm Eastern time, Kelly O’Donnell presents Mrs Medicine: Doctor’s Wives and the Making of Modern American Healthcare, the 7th Annual Michael E. DeBakey Lecture in the History of Medicine, which will be livestreamed globally.

The Thackray Museum’s Insights lecture: Poisons and Cures on 7 October covers the history of insulin with Kersten Hall and the dangerous side of early modern medicines with Elizabeth Hunter.

Tickets for London Month of the Dead events are selling out fast! There are just a few available for Cat Irving’s Exploring Frankenstein's Scientific Roots & Victorian Medical Practices at Highgate Cemetery Chapel on 12 October and The Contagion Chronicles: Plague, Pandemics and Pestilence with Vanessa Harding at Kensal Green Cemetery on 14th October, but be quick!