The gland wizard of California

Dr Clayton E Wheeler offered health and rejuvenation via the medium of goat glands.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The 1920s vogue for gland therapy is relatively well known in the history of quack medicine, largely thanks to John Romulus Brinkley of Milford, Kansas. Brinkley – whose qualifications came from a diploma mill – offered to boost people’s virility by grafting goats’ testicles or ovaries onto their own worn-out gonads.

The gland craze, however, had less well-remembered protagonists. Today I’m focusing on the activities of Dr Clayton E Wheeler (b. 1885), who promoted himself as an endocrine specialist from 1923 until his untimely accidental death in 1935. The title of this post comes from one of Wheeler’s own advertisements, headlined:

REJUVENATION from WITHIN and not from WITHOUT is the Theory of FAMOUS CALIFORNIA GLAND WIZARD.

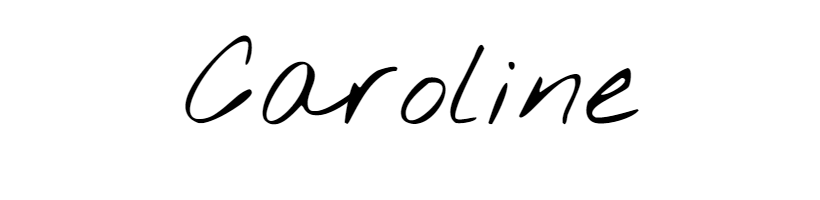

Unlike Brinkley, Wheeler was a qualified doctor with hospital experience in gynaecology. In the early 1920s, he leapt onto the lucrative gland-wagon that promised to delay aging, restore sexual potency and cure a host of chronic conditions. Initially setting up in San Francisco, Wheeler soon opened a Los Angeles clinic too, spending half the week at each and making the long journey by Pullman overnight train. He became so chummy with the railway company that they presented him with a pneumatic mattress for his reserved sleeping berth.

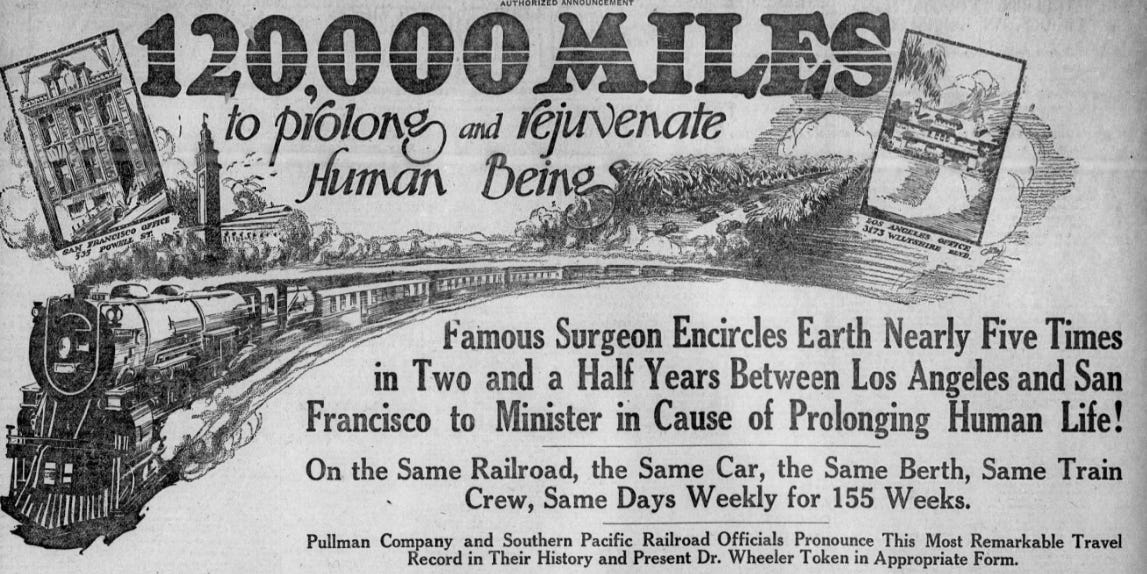

Wheeler targeted his treatment at both sexes and numerous health conditions. These included asthma, arthritis, dementia and epilepsy, plus less tangible problems such as inability to concentrate and general feelings of having lost the vitality of youth. Goat glands were also reputed to prolong life. By 1926, Wheeler claimed to have performed more than 12,000 operations, although this makes the procedure sound more invasive than the reality, which could better be described as an injection.

Details of Wheeler’s methods appear in an article by Ted Le Berthon of the Los Angeles Evening Post-Record in 1924. Le Berthon might have been distracted by the nurses, whom he describes as ‘a slim, bird-like, brunette of a girl’, and a ‘rather buxom, full-blooded rosy-cheeked girl,’ but he does reveal how Wheeler treated his patients.

First, a nurse (the slim one, in case you wondered), injected the patient’s abdomen with a cocaine local anaesthetic. While it took effect, Wheeler peeled ‘a certain potent gland’ off a section of goat hair. He chopped it up in a dish and, when he deemed it sufficiently mashed, he stuffed it into a syringe and injected the anaesthetised area with a thick hypodermic needle:

Swiftly, in the course of a few seconds, Dr Wheeler presses the piston of the syringe, the hashed gland visibly lumping under the pallid flesh.

The procedure took less than seven minutes per person, meaning he could get through many patients in a day. These were people who had simply heard about the procedure and decided to give it a go – they could just turn up and wait, without any referral or formal diagnosis. Le Berthon described the waiting room as being crammed with ‘all races, creeds, colors, nationalities—both sexes.’

Wheeler’s expensive full-page newspaper advertisements highlighted that:

The gonads or generative glands are responsible for inclinations and desires which supply the urge for nearly all human conduct.

Not every patient, however, received mashed-up testes or ovaries – Wheeler used different glands (for example thyroid or adrenal material) depending on the individual’s problem. The ‘worthy poor’ over 50 years of age could get the procedure free of charge. It seems that the goat glands usually just got absorbed by the body, although people did report feeling younger and more energetic.

Wheeler probably copied the injection method from Dr Leo L Stanley, who had been doing experimental gland treatments on the inmates of San Quentin prison for several years (supposedly with their consent, but still). Wheeler had visited him and spoken to the prisoners, but subsequently claimed that he worked with Stanley and had developed his expertise at San Quentin. As Wheeler became more famous, Dr Stanley wrote to the newspapers to confirm that there was no association between them, and he had – for reasons unspecified – banned Wheeler from prison visits some time ago.

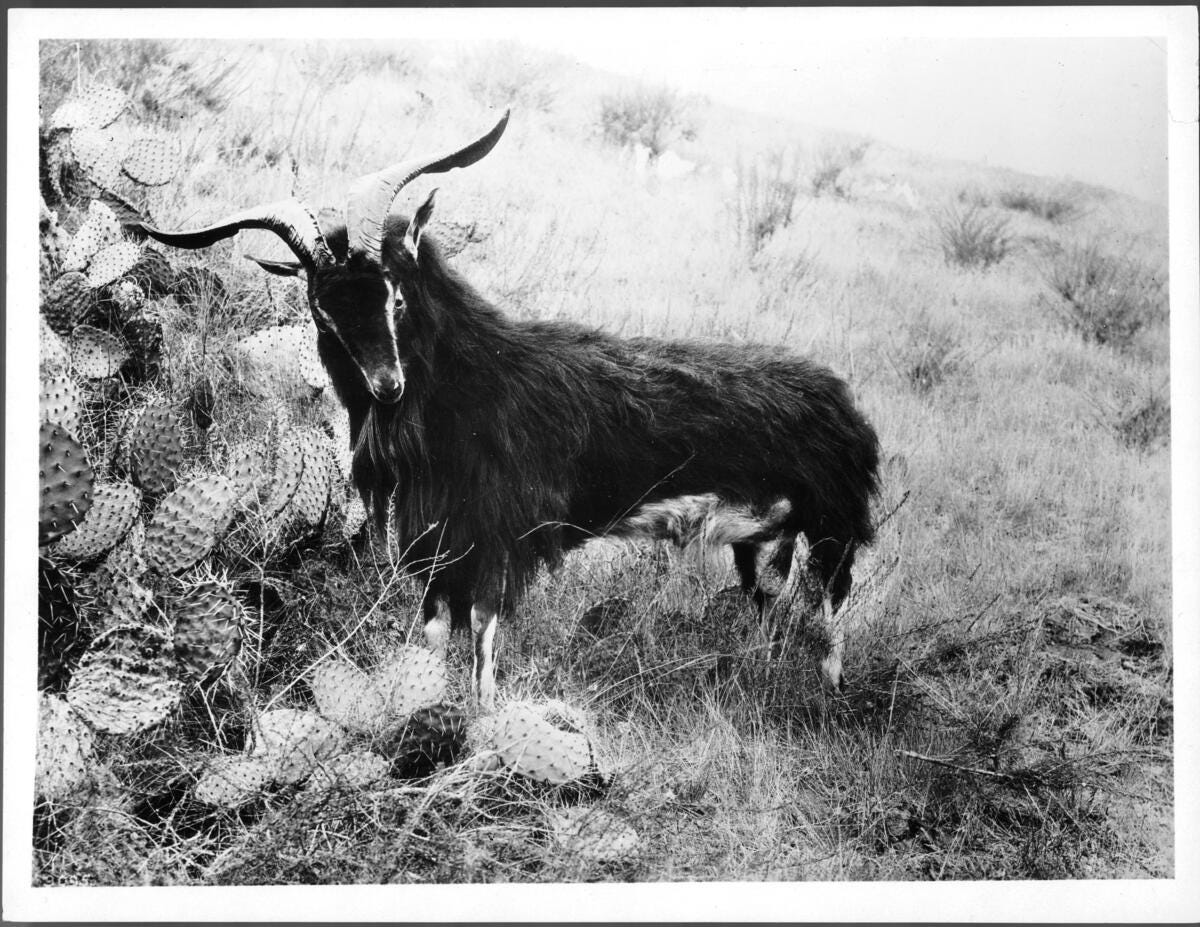

To perform so many goat gland procedures, one needs a constant supply of goats. Wheeler claimed to have secured the entire trade in wild goats from Santa Catalina Island (about 22 miles south west of Los Angeles) and Isla Guadalupe off the west coast of Mexico.

These animals, he said, were ‘the finest specimens of virility’ he had ever seen, and lab tests showed them to be far superior to their domesticated counterparts. Having ‘practically cornered the wild goat supply in the world,’ Wheeler was the only surgeon to go to if you wanted top-notch testes.

Only those within reach of Wheeler’s San Francisco or Los Angeles clinics could access the injection procedure, which necessarily limited the customer base. He therefore introduced a home treatment system available by mail order. This comprised a course of 26 suppositories for daily use, plus four tubes of liquid to be injected into the rectum once a week.

In 1928, the California State Board of Medical Examiners revoked his licence to practise, but he managed to regain it through the courts. Six years later, the Post Office department declared his mail order scheme a fraud and debarred it from the mails. At their hearing, Wheeler listed the ingredients as thyroid gland tissue, pituitary tissue, testicular substance, liver substance, prostatic substance and suprarenal substance. An analysis of the suppositories, however, showed a variable formula, with some samples containing no endocrine tissue at all, just some striated muscle fibres of animal origin. The liquid in the tubes contained some animal material, plus carbolic acid, strychnine and brucine.

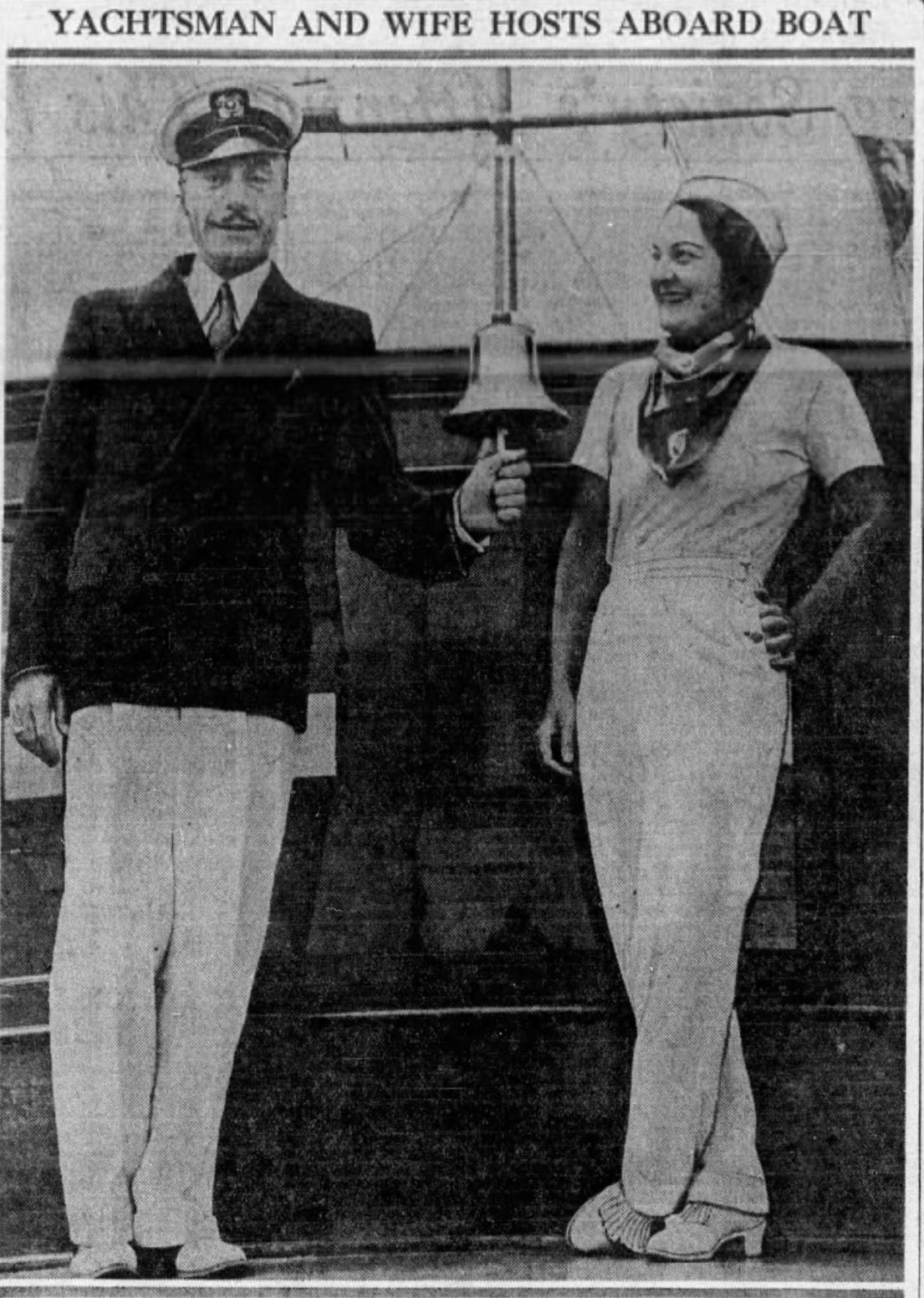

Although Wheeler’s business was under threat, he still managed to act as a society host alongside his wife Hazel. They frequently invited notable people to join them on their luxury power yacht, the Siesta. (As the Journal of the American Medical Association remarked: ‘Yes, quackery pays!’) In 1935, on the way back to the mainland from San Clemente Island, Wheeler entertained his guests with a spot of clay shooting from the Siesta’s deck – but his fun ended in disaster. He slipped over and discharged the shotgun into his own neck, bringing an end to a life and career founded on the perennial human desire for longevity.