The miseries of human life

In 1806, a satirical bestseller detailed some relatable everyday complaints

Plague, pox and poisons, heroic surgery and gruesome injuries might feature significantly in medicine’s past, but our ancestors had to put up with the more mundane side of health preservation too – the annoying colds, aches and grumbles that interrupt our lives regardless of the era in which we live.

In 1806, Rev James Beresford captured these irritations in a humorous work titled The Miseries of Human Life: or the Groans of Samuel Sensitive, and Timothy Testy, with a few Supplementary Sighs from Mrs. Testy. The book was a hit with Georgian Britain’s reading public, and Beresford acquired considerable celebrity for a time. It was reprinted several times, and issued in an expanded two-volume version illustrated by Thomas Rowlandson in 1808. Sir Walter Scott was impressed, writing that the Miseries contained ‘some wit, much humour, and perfect originality.’

Beresford was born in Upham, Hampshire, in 1764. From the ages of nine to 16, he attended Charterhouse School, then went to Merton College, Oxford, graduating BA in 1786. He received his MA in 1798, and became a Fellow of the college. He was Rector of Kibworth Beauchamp in Leicestershire from 1812 until his death in 1840.

I have been a fan of the Miseries since the mid-1990s, when Past Times brought out an abridged version edited by Michelle Lovric. (For non-UK readers, Past Times was a now-defunct chain of gift shops with a historical theme.) The book relates a series of conversations between two grumpy gentlemen, with occasional interjections from family members. They meet regularly to run through all the minor calamities that have befallen them since last time, and others that they remember from their younger days. Beresford and his characters make it clear that these are what would now be referred to as ‘First World Problems’ – nothing of consequence is allowed. They hold no truck with the ‘usurpers, who assume to themselves a prescriptive and exclusive right of suffering, and complaining, on the strength of what they choose to call the greater evils of life.’

Among the health-related miseries on offer is this recognisable description of a villainous cold:

…blowing your nose lustily and frequently, till you are a walking nuisance to all around you—but without any fruits, except a sharp twinging sensation in the nostrils, as the passages which you have forced open close up again, with a shrill, thin, whining whistle—not to mention the necessity of disgusting yourself and friends by pronouncing M like B, and N like D, till you are well.

The aftermath of such an episode leaves you with: ‘your lips being metamorphosed into two boiling barrels, totally disqualified for the functions of eating, speaking, laughing, gaping, whistling and—kissing.’

Even sleep was miserable:

After tossing through a restless night, in sickness, sinking at last into a doze, from which you instantly start broad awake, with the joy of thinking, that you are falling asleep.

Dentistry at the time was an unregulated occupation that anyone could practise. Along with the lack of anaesthesia, this made tooth problems painful and difficult to treat other than by extraction. A particular misery, according to Samuel Sensitive, was:

The interval between the dentist’s confession that your tooth will be difficult to draw, and the commencement of the attempt.

And it wasn’t just your own health that could be a nuisance. You might encounter:

A fellow who treats you in all respects (the fee excepted) like his physician;--unreservedly laying before you, while he is helping you at dinner, all the minutest particulars of his most revolting ailments, from the first attack down to the present moment.

I have picked out these ‘miseries of the body’ due to the theme of this newsletter, but Beresford covered all sorts of aspects of the well-to-do Georgian’s experience. The book contains chapters about the miseries of life in the country (mud), life in London (people), travelling (unexamined sandwiches at awful inns), the dining table (bad teapots) and more. Beresford’s descriptions of socially awkward situations are among the most amusing. There’s the perennial problem of l'esprit de l'escalier:

After having left a company where you have been galled by the raillery of some wag by profession—thinking, at your leisure, of a repartee which, if discharged at the proper moment, would have blown him to atoms.

…and another character who sounds remarkably familiar in these days where critical thinking is not a priority for all:

Seeing a swaggering smatterer in knowledge encircled by his levee of listeners, who blindly recognise his claim to be considered as an oracle;--perpetually, and bowingly, consulting him, and then patiently swallowing the response, like a bolus, without venturing to analyse it.

Being unsociable could leave you with the embarrassment of ‘finding yourself face to face with the very person from whom you had long been concealing, by all possible stratagems, the fact of your being in town.’ Being sociable, meanwhile, could involve ‘dressing for a Ball by an ill-cast looking glass, (not knowing it to be so at the time,) and so mourning over your own unseasonable ugliness.’

The miseries of reading and writing are some of my favourites, with ‘newspaper poetry’ coming in for mockery, and an experience that overtakes me regularly:

As an author—those moments during which you are relieved from the fatigues of composition by finding that your memory, your intellects, your imagination, your spirits, and even the love of your subject, have all, as if with one consent, left you in the lurch.

The first edition of The Miseries of Human Life is available to read online courtesy of the Library of Congress and the Internet Archive. It is also worth trying to get hold of the 1995 Past Times edition if you can, as that contains additional miseries from Beresford’s expanded edition.

Wishing you a week free of misery,

From The Quack Doctor archives

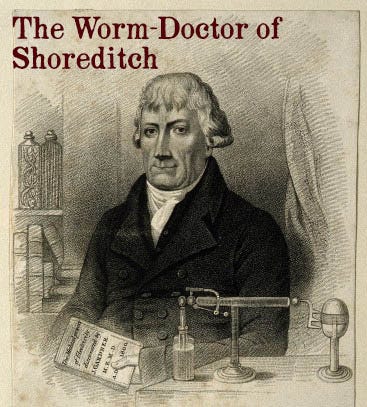

John Gardner, a former soldier, picture-framer and Methodist preacher, became a medicine vendor in the 1780s. His best-known nostrum was a vermifuge, relieving his patients of some spectacular parasitic worms that he collected and preserved in his museums at Long-Acre and Shoreditch.

Early 19th-century anti-quackery publications portrayed Gardner as a hypocrite whose conspicuously pious attitude and motto ‘The Universal Remedy Under God,’ was just a front for charlatanry. The specimens, they claimed, had not passed through any human sphincters but were made by Gardner himself out of everyday substances…