The sad tale of the Talking Fish

In 1859, a new aquatic attraction went on display in London – but it wasn’t exactly as advertised.

Among the dubious entertainments on offer in Victorian London was the wondrous Performing and Talking Fish, who appeared at 191 Piccadilly in 1859. Promotional materials promised a creature in possession of ‘a sagacity bordering upon the dominions of reason.’ We are not strictly within the realms of the history of medicine this week, but I found this story interesting and I hope you will too.

For many people, the publicity must have aroused suspicion that this was yet another Barnum-esque humbug. For others, it was intriguing and worth the shilling admission fee to find out whether conversation with the finny tribe was truly possible.

The writer and artist Charles Allston Collins (1828-1873) was among the spectators. Reporting back as ‘David Fudge, our Eye-Witness’ in All the Year Round, he noted that:

‘…this animal would be described with propriety as the Talking Fish, but for two circumstances—it is not a fish, and it does not talk.’

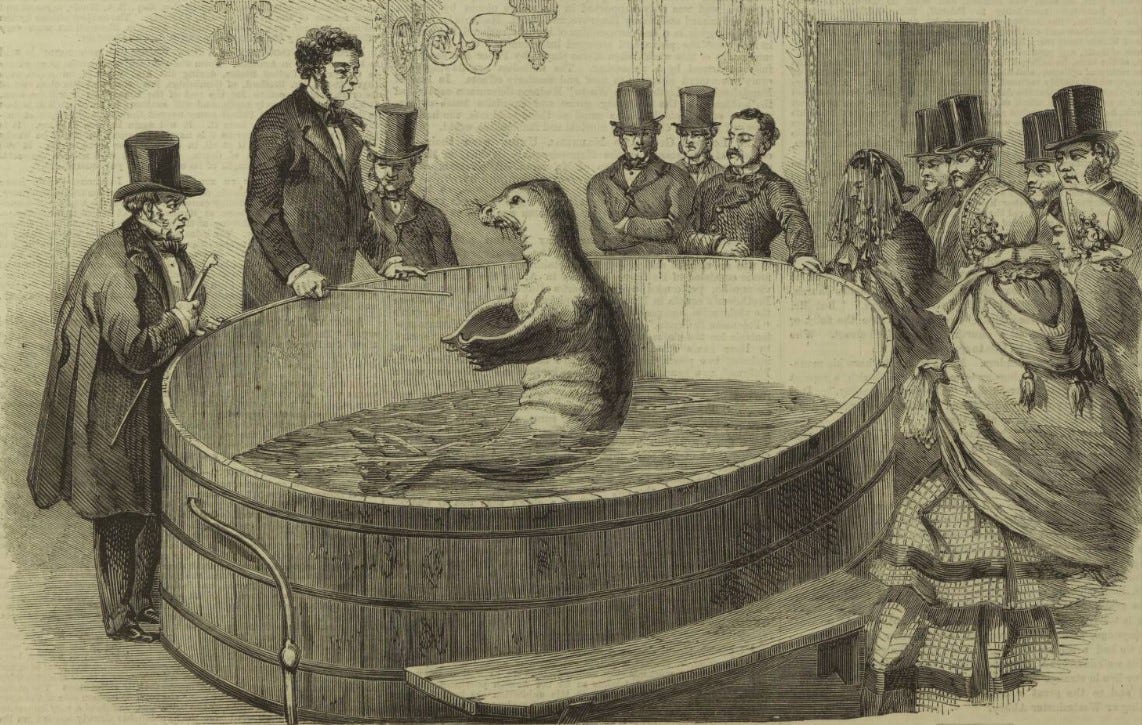

The fish was in fact a seal, identified by several commentators as a female leopard seal of the species Phoca leptonyx (now Hydrurga leptonyx). She had supposedly been captured at the mouth of the Senegal River, which sounds too far north for this Antarctic-dwelling species, and kept at Gibraltar for several years before arriving in Liverpool in 1858 under the guardianship of a Signor Cavani. By this time, she had been trained to respond to commands, and would roll over or shake hands on request. Admittedly, my knowledge of marine biology is mostly gleaned from the Octonauts, but I understand leopard seals to be an aggressive species, and it is surprising to hear that there were no casualties during the exhibition.

Cavani sold her to one Jane Gallagher (who was branching out from running an empire of disreputable houses around Liverpool) for £300 and the seal was from then on exhibited by her and her dodgy partner, Charles Pollard. (Pollard was quite a one – his eventful past included allegedly having tried to steal £2,000 from Napoleon III.)

Mrs Gallagher retained the seal’s keeper, Joshua Benshimol, who had accompanied it from Gibraltar. He appears to have been fond of his charge – whom he called Jenny – and to have done his best to look after her, feeding her up to 50lb of fish a day and keeping her tank clean. His arrangement with his new boss was that he would receive £1 a week in addition to any gratuities from members of the public. As he was to discover, however: ‘…the people who were admitted to see his protégée and hear her speak had so little appreciation of her charms that they were glad to get away without giving him anything.’ (Morning Herald, London, 19 November 1861)

The £1 a week was not forthcoming either and Benshimol later successfully took Mrs Gallagher to court over it.

Some spectators might have been sceptical, but Jenny the seal did have her admirers. The Cheltenham Chronicle (10 May 1859) found her worth visiting ‘in an era when talking men are far too numerous, and talking fishes far too few.’

If the ‘Fish’ part of the attraction was not quite truthful, what of the ‘Talking’ part? The seal’s vocalisations were probably novel enough in themselves for anyone who had never had the chance to see such a creature, but as the London Correspondent of the Commercial Journal (14 May 1859) reported:

‘It does not talk a bit more than a sheep or a donkey. By a great stretch of charity you can make yourself believe that it utters two sounds, one of which is supposed to be ‘mamma’ and the other ‘papa;’ but which is which, it would puzzle a Philadelphia lawyer to say.’

For Charles Allston Collins, the seal did speak – not in words but through her soulful, expressive eyes. His poignant account in All the Year Round (25 June 1859) emphasises his sorrow at the captive animal’s plight:

When your eye-witness entered the exhibition room, and when he saw it lying at the bottom of its tub, he was struck first of all by the creature’s eyes, by their intelligence, their soft beauty, and by the glance of helpless appeal which it directed from one to the other of the faces by which it was surrounded. This was what struck him first. Then it struck him that, if convenient, he should like to have a large ship ready in the Pool of London, to convey the Talking Fish back to the coast of Africa from which it had been brought; then it struck him that as this was perhaps not convenient, he should like to have a rifle loaded with ball, with full liberty to discharge the same at the head of the poor seal, and so put her out of her misery at once and for all.

You do not have to be Sir David Attenborough to realise that keeping an 800lb marine mammal in a small tank in Piccadilly is not conducive to its welfare. Although Joshua Benshimol was kind and caring towards Jenny, she could not thrive in such conditions and in December 1859, the poor creature turned up her flippers and joined the choir invisible.

Perhaps it was for the best that she should suffer no more. Charles Allston Collins had imagined what she would have said if she really could talk:

“What have I done?” she said— “what have I done, that this misery should have come upon me? What is this close and stifling room! What are these faces that gaze at me in my prison? Why am I here? Where is the sea that used to stretch around me further than my eyes could follow? Where the mighty river at whose mouth I live? Where the sun, in which I loved to bask? Where is my mate? They have taken him from me, and killed him. Oh that they would kill me too, and deliver me from this dreadful place!”

24 September 2023: bestselling author Lindsey Fitzharris appears virtually at the National WWI Museum and Memorial in Kansas City to talk about pioneering plastic surgeon Harold Gillies and the hope he restored to disfigured soldiers after the Great War. Free to attend online at 1pm CST (registration required).

Learn about Salisbury’s healthcare history through the photos, documents and objects held in Salisbury District Hospital’s archives. There are three chances to see this presentation by Lesley Self – at Downton on 28 September, Wilton on 29th and Amesbury on 5 October. More info here.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society in London E1W 1AW is hosting a profession-wide celebration of Black History Month on 11 October, 5.30pm-8pm. ‘Saluting our Sisters’ is dedicated to honouring the achievements of Black women in British pharmacy.

12 Oct 2023: The Royal College of Nursing Libraries have a free online event about Irish nurses working in the NHS in the 1950s and 60s. Louise Ryan and Grainne McPolin present this illustrated talk drawing on a fascinating oral history project.