The tooth, the whole tooth … and the jawbone too

18th-century dentist Thomas Berdmore revealed the agonies his patients endured before, during and after treatment.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from the history of medicine and related themes.

It’s free to subscribe, but if you would like to make a one-off contribution to the coffee supplies that keep me going, please go to my Ko-fi page here. Thank you!

An 18th-century sea voyage from the East Indies to Great Britain was at best tedious and at worst fatal, should disaster befall the vessel or disease break out on board.

For one gentleman in the 1760s, the last three months of the journey – though uneventful in terms of pirates, plagues and that sort of thing – were miserable thanks to the mouth ulcers that gnawed at his gums.

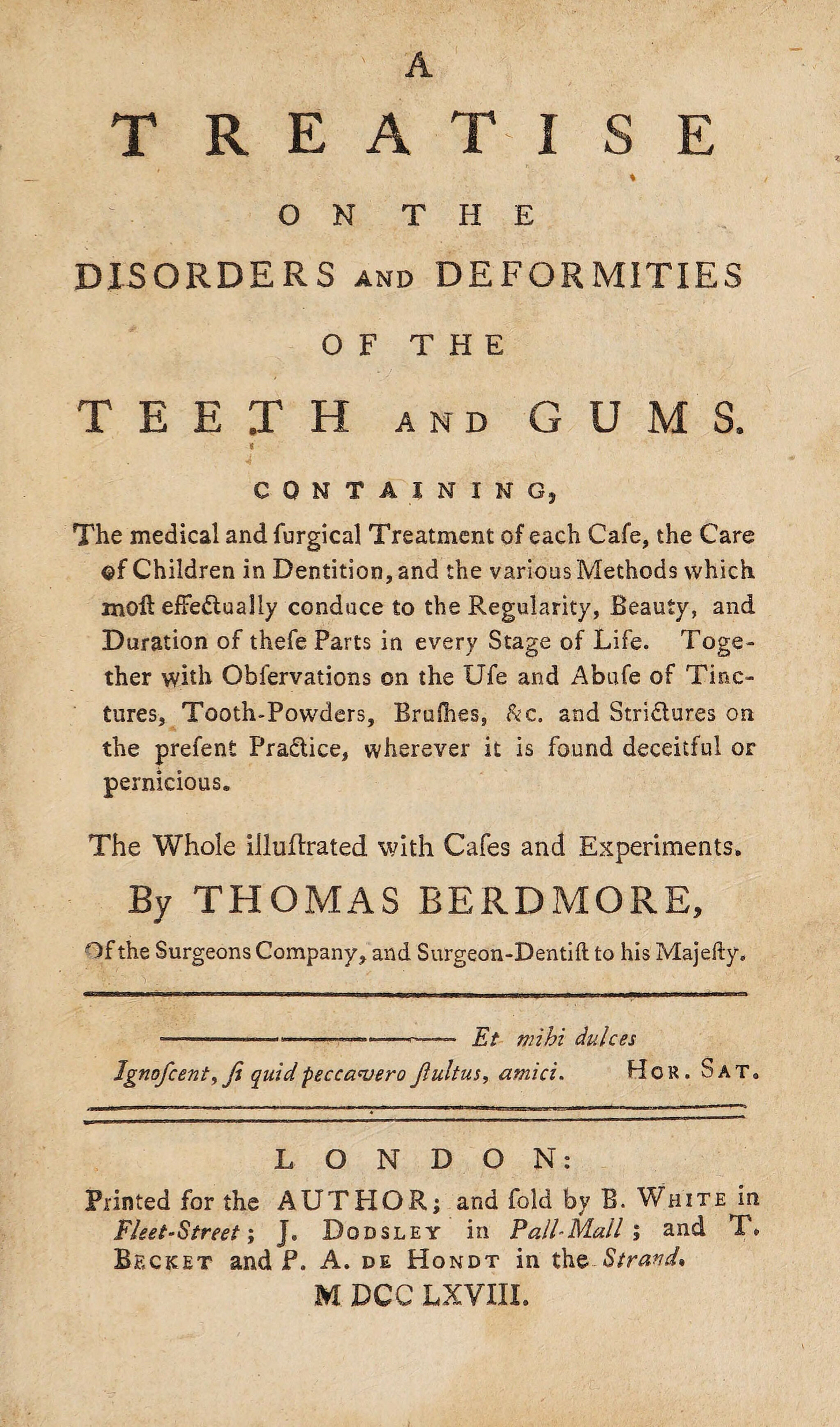

His case is among those related by Thomas Berdmore (1740-85), surgeon-dentist to King George III, in his concise and accessible A Treatise on the Disorders and Deformities of the Teeth and Gums (1768). At this period, English-language dental information was scarce; Pierre Fauchard’s 1728 book Le Chirurgeon Dentiste approached the subject in a detailed scientific way that would lead to the author becoming known as ‘the father of dentistry’, but it was only available in French and German. The average English-speaking tooth-drawer didn’t have the education to benefit from the French dentist’s wisdom. Berdmore sought to fill this literary cavity and improve practitioners’ knowledge of anatomy and dental disease, as well as informing the public about the importance of tooth care in keeping the rest of the body healthy.

While some people practising dentistry had – like Berdmore – trained as surgeons before specialising in teeth, others offered tooth extraction as an adjunct to their main calling as barbers or blacksmiths, and still others were classed as mountebanks, who travelled around ready to ‘whip out a Tooth before the patient can look about him.’ For those in pain, these practitioners provided a valuable service – but their skill levels varied, and the desperate patient had to weigh up the risk of a broken jaw or fatal blood loss.

Because Berdmore includes case histories from his own practice, his treatise has a strong human-interest element that highlights the reality of dental health in the 1700s. While it is a cliché to assume everyone ‘in the olden days’ had awful teeth, Berdmore’s patients were not exactly sporting the pearly white gnashers of present-day celebs.

Our gentleman travelling from the East Indies arrived safely on British soil and his ulcers improved for a while. A few months later, however, a painful swelling appeared on his gum, getting bigger every day. He thought it would ‘come to a head’ and resolve of its own accord, so ‘he neglected it two or three months longer, by which time it became as large as a walnut, very painful, and affected his speech.’ A friend, who suspected that the man’s lack of oral hygiene had something to do with it, advised him to consult Berdmore.

He readily agreed to let Berdmore cut the whole growth out, but after the procedure, ‘The blood poured forth very quickly, and the astringent liquor, which I advised him to keep in his mouth, did not check it in the least.’

Berdmore made a compress using agaric (a type of tree fungus reputed to stem bleeding) and linen, but when he took this off after a couple of hours, the blood still flowed.

After a few days of astringent gargles, Berdmore ‘thought it best to commit it to nature,’ which is a rather elegant way of telling the patient to go away. The excrescence, however, ‘began to shoot forth again’ and the gentleman returned for further treatment. Berdmore advised frequent applications of burnt alum and Roman vitriol (copper (II) sulphate) and the lesion eventually healed.

Another patient, a 23-year-old man who worked for a bank, asked Berdmore for advice about his unusual-looking and painful teeth. Berdmore found them completely encrusted with a thick layer of tartar ‘by which each set was united into one continued piece, without any distinction, to show the interstices of the Teeth, or their figure or size.’

In places the tartar was half an inch thick, pushing the man’s lips outwards. Berdmore chipped away at it in daily instalments for a fortnight, and then instructed the patient to brush his teeth and gums two or three times a day.

Six months later, the banker was back, and Berdmore ‘found his Teeth covered with a new crust of the former kind, as thick as a crown piece.’ He once again removed the tartar and recommended a more abrasive tooth powder and a harder brush.

Berdmore often had to pick up the pieces of unskilled operators’ handiwork, as in the case of a young woman whom he had attended about five years before he wrote his book.

She suffered a toothache and asked a barber-surgeon to extract the offending molar. He struggled to get the tooth out, but convinced the patient to let him try again with different tools.

He fixed his instrument, and with a sudden exertion of all his strength, he brought away the affected Tooth, together with a piece of the jaw-bone, as big as a walnut, and three neighbouring Molares.

(A walnut appears to be the standard unit of measurement in these instances.)

The young woman’s family sent for Berdmore within a few hours of the operation and he arranged bloodletting and purgatives to combat the violent inflammation of her throat and face. The family evidently expected him to pop the jaw and teeth back in and make her as good as new again. They were disappointed that he couldn’t work such a miracle, but they followed his instructions about wound care and it did ultimately heal – albeit leaving her with permanent discomfort and disfiguration.

Berdmore’s Treatise does an admirable job of imparting the up-to-date dental knowledge of his time to both practitioners and patients. For me, however, his real-life cases stand out; they are snapshots of suffering within the lives of people whose stories are otherwise lost. The patients endured so much from their dental conditions – and even more from the attempts to treat them – with astounding courage and resilience that resonate today.

While procedures, qualifications and regulation have made dental care safer and less agonising since Berdmore’s day, issues of access and affordability are still leaving patients suffering for longer than they should have to.

Dentistry filled me with horrors when writing my book. This piece was a terrific reminder of however much we hate the dentist, and however difficult it is to find treatment, we must never have to resort to these means again.