The woman who turned to charcoal

A unique medical condition was not all it seemed in 1860s New York.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Thirty-six-year-old Miss A Perry lived with her parents in Lenox, Madison County, NY. In 1861, her unique medical condition brought her to the attention of Dr A G Purdy, who was intrigued by her bizarre symptoms.

Miss Perry ate and drank normally, but had not passed any urine for six years. Even more oddly, her bodily waste appeared to be excreted through her skin; her face, left arm and left leg had turned black with a scaly coating like dried blood. Sometimes she coughed up a substance that looked like charcoal.

Dr Purdy wrote up the case for the Transactions of the Medical Society of the State of New York. Having described it, he concluded: ‘I cannot say there is no deception in this case, but think the above statement substantially correct.’

His uncertainty turned out to be justified. In June 1862 Miss Perry, under the care of a physician called Dr E Perkins, turned up in New York City. She was to be exhibited to high society as ‘The Charcoal Woman’, a wonder of the age; Dr Perkins presumably fancied himself as the next Barnum.

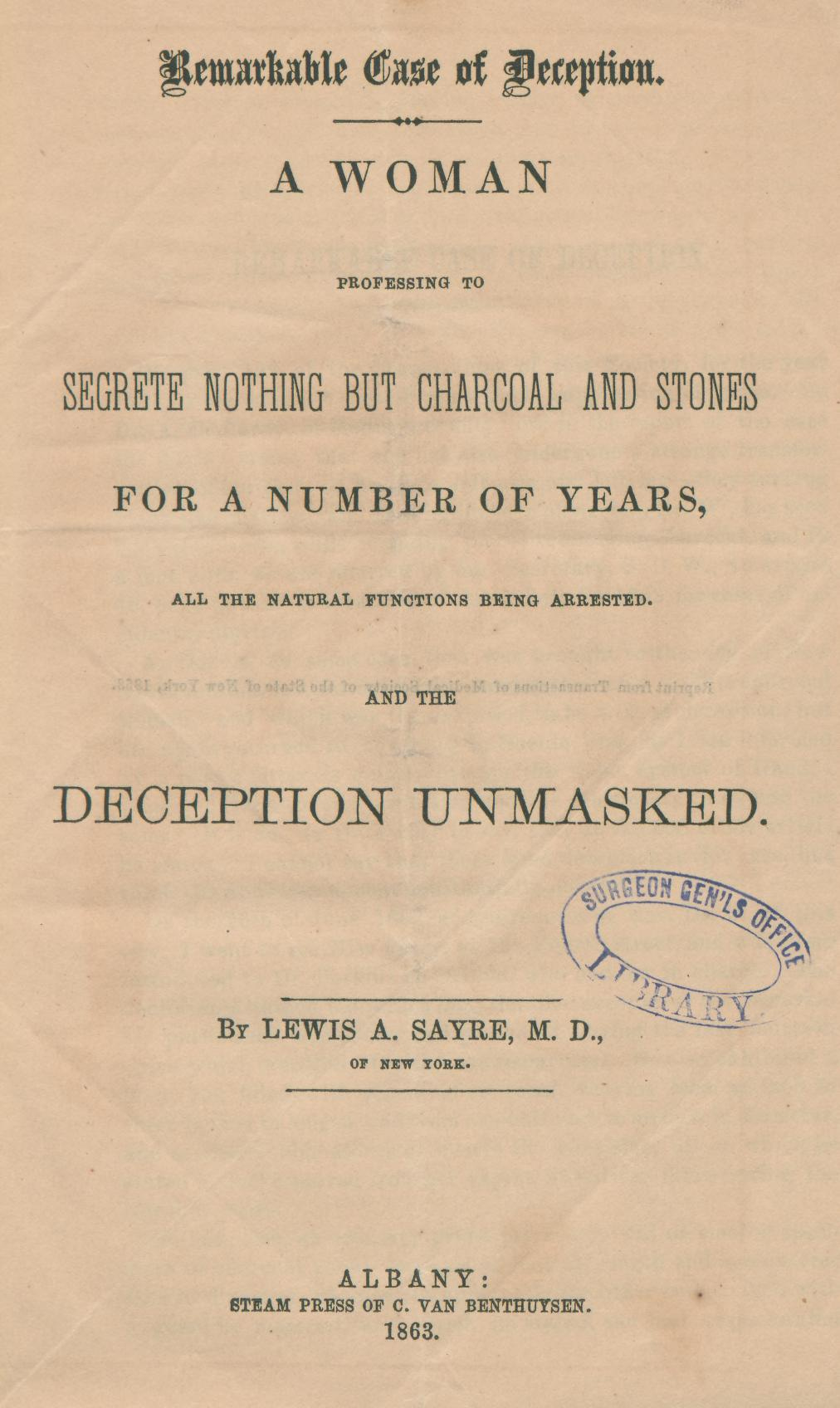

Among those invited to her lodgings at 196 Fourth Street was Dr Lewis A Sayre (1820-1900). Sayre is now best remembered as an orthopaedic surgeon who corrected scoliosis and spondylitis by suspending the patient by the arms and head and using a plaster of Paris body cast to immobilise the spine. His 1863 article A Remarkable Case of Deception is a minor part of his body of work but gives some fascinating detail about Miss Perry’s strange condition.

Sayre initially met Dr Perkins, and listened to the ‘patter’ necessary to any self-respecting showman:

‘The doctor entertained me with a long, detailed account of the remarkable phenomena which she had presented in the last fourteen years, which is entirely too tedious to narrate.’

Perkins also displayed a collection of charcoal pieces that he claimed to have removed from Miss Perry’s vagina over the last four years. Sayre then met the patient, who appeared as she does in the picture above. He immediately suspected something dodgy.

‘A close investigation of the mask, around the mouth, showed me that it was not attached to the skin—was not an exudation from it, and I thought by being cut loose from its attachments to the hair, and the band which was placed around her forehead, could have been easily removed.’

When he tried, however, Miss Perry went into hysterical convulsions. Neither she nor Dr Perkins would allow Sayre to remove the bandages at each end of the black coating on her arm.

Miss Perry had a similar coating on her leg, and Dr Sayre noticed a hole in it. When no one was looking, he whipped out a pair of scissors and cut off a section of whatever it was, seeing healthy skin underneath.

On examination, he found it the sample ‘to be made of cotton and gum, covered with some black substance.’ Miss Perry’s niece and the local clergyman immediately accepted that they had been hoaxed.

Her other relatives, however, did not believe Sayre and invited him back with other prominent physicians. This time, the patient’s face was clear, and Dr Perkins explained that the coating usually fell off at night. He could not produce any samples, but said that the visitors had arrived just the right time, for Miss Perry was about to pass a piece of coal from her vagina. The coal having been extracted, Dr Perkins asked the spectators for their views.

‘When my opinion was asked,’ wrote Sayre, ‘I stated that the whole affair was a gross deception, that the Dr. was a swindling rascal, and that he knew it.’

Dr Perkins made himself scarce, and Sayre had Miss Perry admitted to Bellevue Hospital, where the charcoal did not return. She still claimed to be unable to pass water, but the area next to her bed became wet and another patient reported seeing her urinate on the floor.

Although discharged from hospital as cured, Miss Perry seems to have had a compulsion to continue creating her strange symptoms. She asked the house surgeon what he would think if the disease returned a few weeks after she got home. Sayre suspected this meant she would try again.

With Dr Perkins now out of the picture, it was clearly not just a case of him exploiting her. The next Sayre heard, Miss Perry had recruited another doctor and a ‘committee of ladies’ to help her maintain her role as an anomaly of nature.

It would be anachronistic to suggest that Miss Perry had Munchausen Syndrome, but there was clearly more going on with her than the simple desire to make money as a ‘freak’. Little information survives about her family background or any trauma she had suffered.

Did she find solace in the compassion and attention she received as an invalid? Was she just a hoaxer enjoying wielding power over others? Was she trying to avoid the challenges and mundanities of everyday life, or process psychological distress through fabricated physical symptoms? Perhaps she had a real illness that no one would acknowledge unless she exaggerated it.

Sayre was not sympathetic or even interested in anything underlying her behaviour. He interpreted the condition as ‘nymphomania’ but did not expand on his reasons for thinking this – presumably it was because the claims of charcoal in the vagina led to frequent manual examinations. His main object in writing about her was to warn the medical profession and the public that she might try to scam them.

It is interesting that the only time she is recorded as saying anything is on leaving hospital – perhaps listening to her would have gone some way towards solving the mystery.