The wonder-worker Madame Enault

In 1879, a medicine show featuring dentistry and music created hype in the north of England

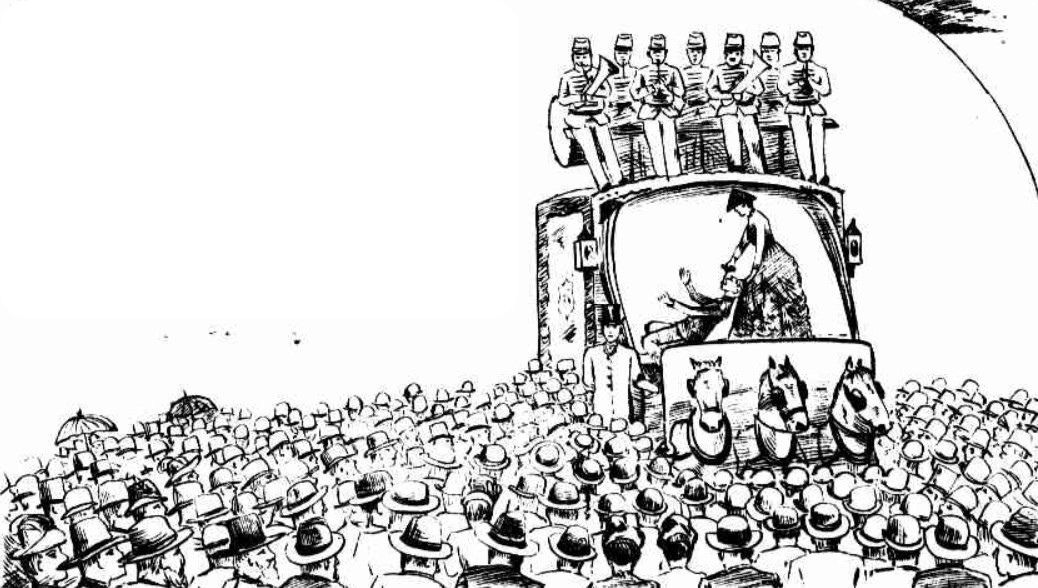

In the open spaces on the edges of town, an exotic figure by the name of Madame Enault commanded the attention of huge crowds. Standing aboard her gilded circus-style chariot, this mysterious woman in an ornate costume promised – by means of an interpreter – to use ‘Indian Malachite’ and ‘Chinese Caustic’ to cure all her audience’s ailments.

Madame Josephine Enault (c.1842-1894) and her assistant Paul Duflot appeared in northern England in 1879 – a time when the idea of female doctors was becoming familiar but still held a sense of novelty. She claimed to be the daughter of a physician in Rome, to have studied medicine at several continental universities and to have been in practice for 18 years – but her showmanship and cure-all elixirs did nothing for the efforts of women doctors to be taken seriously.

Madame Enault drew a crowd by offering free tooth-pulling and the instant cure of minor ailments, before launching into a pitch for her medicines. Her methods remind me of the better-known Sequah, who toured the UK and beyond in the 1890s. But while Sequah adopted a Wild West theme and claimed to have gained his healing wisdom from Native American elders, Madame Enault took inspiration from the East. Her medicines were said to contain 250 oriental herbs, none of which could be found in Europe, and she performed ‘… resplendent in scarlet and velvet and gold.’ (Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, Saturday 24 July 1880).

On top of her carriage sat seven or eight musicians, looking ‘exceedingly miserable and uncomfortable.’ The Independent surmised that ‘frequent doses of their own music have probably induced this unhappy expression.’ Their role was to play while patients had their teeth out; whether the purpose of this was to drown out the screams or add to their torture for some other reason is unknown, but the paper described it as ‘an awful addition to the pain’.

As well as drawing teeth, Madame Enault specialised in removing wens from people’s skin. These sebaceous cysts often affected the scalp, and her procedure is described in an account of her treating an elderly man at Birkenhead in October 1879.

She cut off the hair around the lump and then dressed it with lint saturated in ‘Indian Malachite’. She tied the man’s handkerchief across his head and under his chin to keep it in place, and left him to sit quietly for a quarter of an hour while she treated other patients. In due course, she returned to the old man and took the dressing from his head.

… she seemed dexterously to wrench it from its place, and then to hold up to the people a gristly lump, and having put some saturated lint onto the head again, she bade him go.’ (Liverpool Albion, 18 Oct 1879.)

Richard Nicholson, a mason who had seen Madame Enault in St Helens, explained what was really going on. He had partially lost his hearing, and was anxious to find a cure. He attempted for a few days to gain admittance to Madame Enault’s carriage, but was turned away. Finally, he got a policeman mate of his to help him push through the crowd, and was examined by another doctor – possibly Paul Duflot, Madame’s assistant and later husband – who said he could go up on the stage. Nicholson, however, felt a tickling sensation in his ear and discovered that the assistant had put into it ‘a piece of prepared substance, fleshy-looking’. He realised the whole thing was a sham but decided to go ahead and see what would happen. Madame Enault put some malachite-soaked cotton wool in his ears and asked him to wait for half an hour. She then ‘took an instrument and extracted the prepared polypus’, holding it up for the audience’s admiration. When he attempted to expose the imposture, he was bundled off the carriage, handed a bottle and half a crown, and given ‘a look as much to say, “Go away and don’t say anything”’ (Birkenhead News, 4 October 1879).

The dentistry and wen-removal were performed free of charge, creating a potential mutual benefit for practitioner and patient. For patients who could not afford to visit a qualified dentist, the removal of an agonising tooth (if done properly) granted relief. From Madame Enault’s point of view, the free treatment brought the crowds and created buzz around her presence. Once they were there, she could do a sales pitch for the ‘Indian Malachite’ and ‘Chinese Caustic,’ and shift hundreds of bottles at 2s each. While in Birkenhead, she was said to be taking £500 a week.

Lack of dental regulation meant that it was difficult to tell whether a dentist had any qualifications – historically, it had been possible for anyone to put up a sign saying ‘dentist’ outside their house and gain their first experience of tooth extraction as and when a patient turned up. You were not necessarily any worse off with the likes of Madame Enault. The Chemist and Druggist wrote: ‘She is apparently endowed with more than ordinary strength and extraordinary skill, for she draws the teeth very rapidly and successfully,’ but there were reportedly dissatisfied customers too, who were left in pain with broken stumps.

When Madame Enault visited Sheffield in 1880, the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent went on a crusade against her, denouncing her as ‘a vulgar imitation of the old Italian mountebanks’. The paper asked Alfred Allen, the Borough Analyst, to investigate the remedies. He concluded that the Chinese Caustic comprised wax, oil, Vaseline and some variety of turpentine, while the Indian Malachite or Balm was made up of glycerine and spirits of wine, scented with peppermint and cassia, possibly with some coal-tar dye in it to make it green.

After this, she spent time in Glasgow and then moved to Canada, taking her show to Montreal and Toronto. In the early 1880s, her husband Pierre Enault died and she married her business associate Paul Duflot. By 1887 they were operating in Australia and New Zealand as ‘Dr and Madame Duflot, the French-Canadian healers’ – but tragedy overtook them. Madame’s 20-year-old son Jules drowned in Lake Ellesmere near Christchurch, leaving his mother heartbroken. The show went on, but with further setbacks. In 1893, Paul Duflot, described by one newspaper as ‘a sleek, cunning-looking customer’, was charged with manslaughter after allegedly prescribing poisonous powders to a lady called Mrs Gardiner in Warrnambool, Victoria. A point against him was that ‘in these days of science and progress the man who guaranteed to cure all diseases with one medicine was either a fool or a rogue’, (The Argus, 10 August 1893) but he was ultimately acquitted. Just a few months later, Madame Duflot herself died in Melbourne at the age of 51. She was succeeded by another of her sons, Joseph, who set up his own medicine show as ‘Professor Tarasca’.

HistMed Highlights

COMEDY: 🎭 Science Showoff Cures All Ills is an evening of medically-themed stand-up comedy, stories, and silliness from some of London’s funniest people. 8 November 2023, 6pm at the Old Operating Theatre Museum. £20.

LECTURE: 📜The Museum of Healthcare in Kingston, Ontario, hosts the 2023 Margaret Angus Research Fellowship Lecture. Jessica Sealey presents Monstrous Instruments: The Vaginal Speculum and the Contagious Diseases Acts Repeal Movement on 9 November 2023, 7pm, at Queen’s University, Kingston.

EXHIBITION: 🧸Once upon a time: a history of children and young people’s nursing opens at the Royal College of Nursing in Cavendish Square, London. Explore emotive tokens from the historic Foundling Hospital, children’s artwork from Bethlem Museum of the Mind, and objects and stories loaned by nurses past and present. 9 November 2023 - 27 April 2024, free admission.

TOUR: 🎫Gladstone’s Land in Edinburgh’s Royal Mile offers a Medical Tales tour, bringing to light the city’s medical history from Old Town disrepair to the advancement of surgeons and even the Black Death. 10 November, 4pm, £12.