'This comedy of knave and dupe'

A quack doctor in 1870s Hull told some incredible tales about his Indian Remedy.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

John Richardson, a 29-year-old farm manager from Easington in east Yorkshire, felt under the weather. He had been reading a book called Anti-Lancet by Dr Charles Rooke of Scarborough, proprietor of the Solar Elixir, Golden Ointment and Oriental Pills. This had done little to reassure him that he would be all right.

Rooke argued that all disease stemmed from nervous debility – a term shadowy enough to cover everything, but coded as a precursor to impotence in men. Although claiming legitimate qualifications himself, Rooke dismissed orthodox medicine as ‘a wilderness of opinions founded on error and supported by bigotry and prejudice.’1

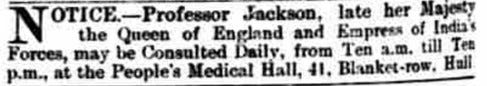

While in Hull one day in 1872, and labouring under the preoccupations primed by his reading material, Richardson noticed a poster in a shop window describing the wonderful effects of the ‘Indian Remedy’ available within. This sounded very much like the Indian herbs in Rooke’s medicines, so he went in to buy a bottle and encountered ‘Professor Henry Jackson’. The Professor expressed concern that Richardson might be too far gone to benefit from the treatment – but some tests would tell him more.

First, Richardson had to blow into a glass of water, which at once turned white like milk (we can safely assume it was limewater). This, said Professor Jackson, was bad, bad news. It indicated that Richardson was in a ‘low state’ and had three months to live, if that.

Next, the Professor produced a glass of red liquid and asked Richardson to blow into that too. Nothing happened, which was even worse news. Because the liquid did not boil on contact with his breath, this meant Richardson had no circulation of the blood and could die at any moment.

The third test involved holding a ‘pulse glass’ in a horizontal position. The standard use for this instrument was to time half a minute while the doctor took the patient’s pulse, but Jackson seems to have credited it with more mysterious powers. It showed that Richardson’s heart had ‘no pulsation’ (and yet was also somehow going at a rate of 120 beats per minute).

All these devices, Jackson said, came from India. He was the only person in England authorised to sell them and their accompanying medicines.

Richardson signed up to pay two guineas a month for medicine and advice. At a later date, he also bought a pulse glass for 14s. 6d, and a small bottle of liquid called galvanic fluid for a guinea. He was supposed to pour some of this into the palm of one hand and hold the glass with the other; this would ‘electrify him’.

Other medicines supplied to Richardson included manna – the genuine article left behind after the children of Israel had eaten all they needed in the wilderness. Trees covered in manna had been transplanted to India, and now this bread of life could be gathered there and shipped to Hull. The venerable Indian balsam merchant with whom Jackson traded had taken this substance and lived to be 170 years old. Continuing the holy theme was an ointment made from spikenard, supposed to be that with which Mary anointed the feet of Jesus Christ at Bethany.

In case any doubt arose about the veracity of these medicines, Jackson showed Richardson a testimonial letter from an Egyptian named Smith. Who could argue with that?

Richardson next bought a case of Indian Remedy for the extortionate sum of £51. The inside of the lid displayed an inscription:

The great Indian Remedy. The blood, the blood; herbs, plants, gums and balsams. The great blood purifier and restorer, warranted to cleanse the blood from all impure matter. Prepared with the greatest care from the prescription of an eminent Indian physician, and recommended by all eminent members of the medical profession for indigestion, loss of appetite, rheumatism, and all diseases of the heart, head, chest, liver, lungs, kidneys. Being a direct purifier of the blood, they contain no mercury or mineral of any kind.2

Jackson also sold his customer a galvanic belt, and told him that he had been to India as a ship’s surgeon, saved 600 lives during the Battle of Dehli and performed many amputations.

Eventually, and at least £175 lighter of pocket, Richardson wised up and told the police that Jackson had defrauded him.

In court, the solicitor for the prosecution admitted that:

‘The first thing which would probably occur to the minds of the jury was that the prosecutor [Richardson] was a very credulous person.’ Even if this were the case, however, ‘the credulity of the victim was no defence on the part of the victimiser.’3

An expert witness, Dr Munroe, deposed that the glass instruments were of no use whatsoever, and were mostly just children’s science toys. Some of the medicine bottles contained chloride of potash and others just coloured water sweetened with sugar. The ‘manna’ was effervescent magnesia and the spikenard was scented lard.

The box in which the Indian Remedy had been presented to Richardson turned out to have once contained Swiss Bricks– a set of children’s building blocks – with foil covering up the original branding.

The defence pointed out that John Richardson had enough brains to manage his uncle’s 200-acre farm, including keeping the accounts, which made it difficult to believe that he had genuinely been taken in. Jackson might have jovially mentioned the fantastic stories behind the medicines, but Richardson wasn’t meant to have taken them seriously.

Some commentators were unsympathetic towards Richardson. The Daily Telegraph described him as ‘the victim in this comedy of Knave and Dupe,’ and ‘a descendant, in the way of temperament at least, of Molière’s “Malade Imaginaire”’.4

Meanwhile The Echo, while acknowledging that a crime had been committed, opined that:

It is difficult to resist the conviction that Mr Richardson, the prosecutor, was a pigeon whom it was almost impossible for a man with the slightest tinge of roguery in him, to resist the temptation to pluck.5

The jury, however, found Henry Jackson guilty of fraudulently obtaining money by false pretences and he was sentenced to 12 months’ hard labour in Wakefield Prison. Fortunately, by the time of the trial, John Richardson’s health problems had got better of their own accord.

The concerns about health and the description of how to cure them are both really interesting despite the quackery. The discourse regarding the heart, circulation, and pulse shows that these played an important role in how British men conceived of health. The fact that India cures were seen as potentially legitimate also suggests much about this culture.

Really interesting and well done.