'A sinister parasite on the community': Dr S R Chamley (part 1)

An audacious early-20thC 'cancer quack' scammed thousands of dollars from vulnerable patients

Catherine Nevin’s death certificate stated that she died of cancer. The 33-year-old woman from Wells, Nevada, had consulted cancer specialist Dr S R Chamley and undergone surgery at his office in Third Street, San Francisco in February 1903. Within a week, she was dead.

Mrs Nevin’s husband and his brother worked out there was more to this tragic event than Chamley would admit. After appealing to the Coroner, they discovered that the certificate should have read ‘Death by haemorrhage, due to operative wound.’ Chamley had effectively killed her.

Samuel Ricket Chamley (1852-1920) was one of San Francisco’s most ruthless medical scammers – and that’s saying something, as the Daily Nevada Star estimated that the city teemed with at least 700 quacks in 1903. His long career brought him hundreds of thousands of dollars, all fleeced from people either suffering from cancer or vulnerable to persuasion that they had it. The fact that he had a genuine medical degree, achieved in 1884 at Keokuk in Iowa, helped him get away with it for so long.

In court before the Coroner’s jury, Chamley appeared ‘wearing a Transvaal gem as large as a 10-cent piece and a somewhat faded professional silk hat.’ When questioned why he did not ligate the thoracic artery, he said he couldn’t find it, so had tried to stem the bleeding with pressure. (The San Francisco Call and Post, 12 Feb 1903.)

He was subsequently charged with the manslaughter of Mrs Nevin, but the case was thrown out due to lack of evidence. He did lose his licence to practise but was soon taking out huge newspaper advertisements crowing about being exonerated from charges brought by ‘jealous physicians, aided and abetted by a discharged employee.’ (SF Examiner, 3 May 1903)

The employee in question was Dr Charles B Waller, a recent graduate of the Eclectic School of medicine. He had joined Chamley’s company and quickly attained the title of head operator, but was disillusioned with the state of what Chamley called his hospital or sanatorium. Testifying against his former boss, Waller described it as a rooming-house, with accommodation let out to lodgers when not occupied by patients – ‘anyone may sleep in a bed where a cancer patient has died the night before.’ There was one unqualified nurse, and the patients were locked in their rooms overnight with no means of calling for help. Mrs Nevin was not the first person to have died shortly after surgery. Reporting on the case, the San Francisco Call and Post commented that the place ‘would rival the pesthouses of medieval Europe’. (SF Call and Post, 12 Feb 1903.)

Later that year, Chamley encountered Waller on the street and beat him up. Once again, he doesn’t seem to have faced any consequences.

He did, however, expand from San Francisco and establish businesses in St Louis, Los Angeles and Chicago over the next decade, often running several at once with the help of a qualified physician to oversee each location.

We have seen how Chamley treated his patients, but how did he find them in the first place? An investigation led by Dr Max E Starkloff, the city health commissioner for St Louis, reveals all. In 1916, his assistant Dr German A Jordan reported to the American Public Health Association about the work done to tackle St Louis’s thriving fraudulent medicine scene between 1907 and 1910. This project had left the team ‘astonished to find how great a number of fakers were fleecing the unfortunate.’1

The investigators began by scouring the newspapers for anyone advertising medical services. They then cross-referenced this information to the medical register. Anyone whose credentials didn’t match up had to provide proof of entitlement to practise, or immediately discontinue. This cleared the field to some extent, but die-hard charlatans like Chamley were not deterred.

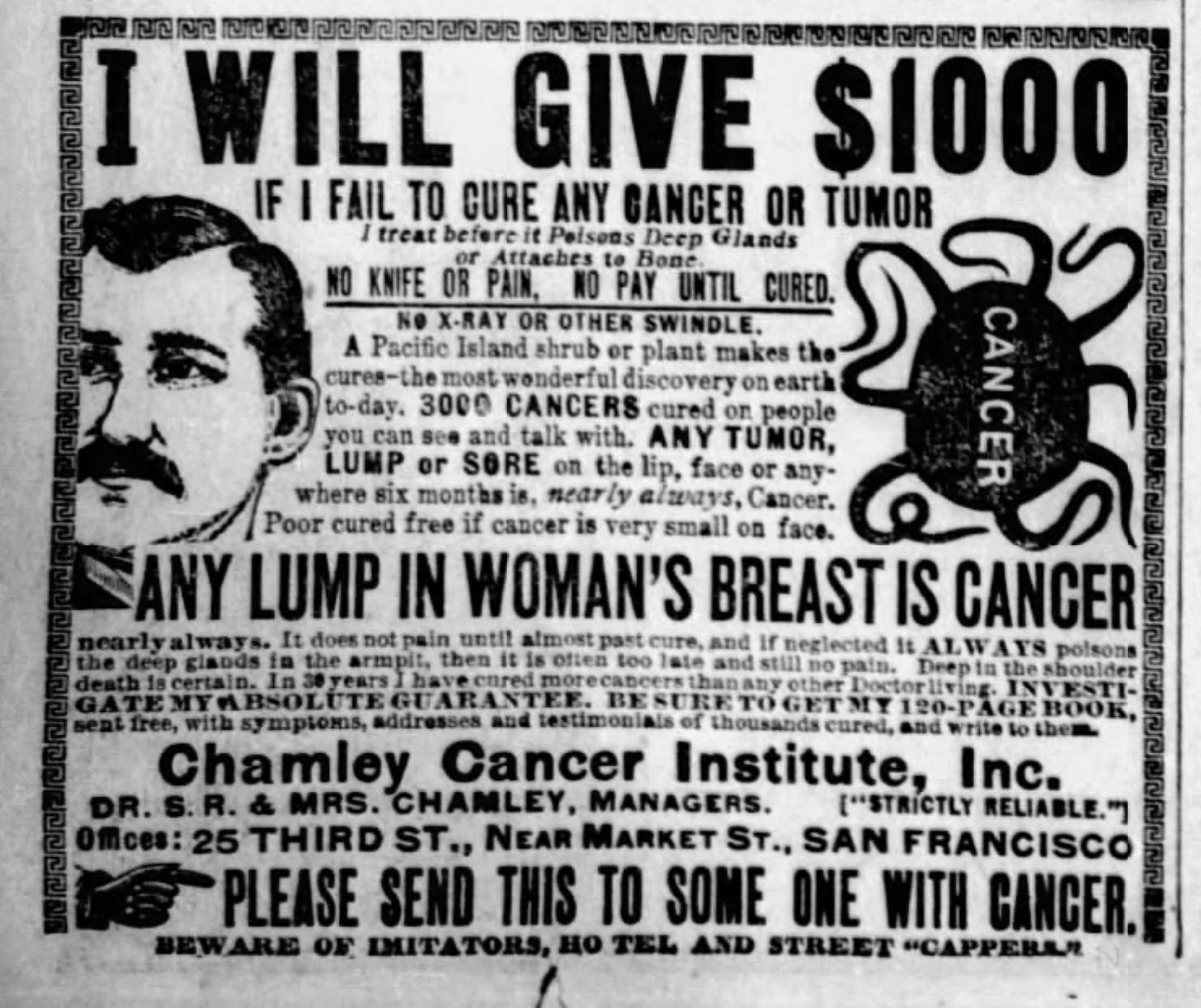

Dr Jordan’s report details Chamley’s modus operandi. Advertisements similar to the San Francisco one above, with their terrifying assertion that ‘any lump in woman’s breast is cancer,’ brought in enquiries from frightened people. The reply would confirm that their symptoms were indeed cancer and urge them to attend Chamley’s office without delay. Those ignoring this found themselves inundated with ‘scare letters’, each more strongly worded than the last. If it became clear they weren’t going to attend in person, Chamley offered to sell them a home treatment – the nature of which I will return to in part two of this story.

As every case was diagnosed as cancer, all Chamlee had to assess was the health of the patient’s wallet. He quoted a treatment cost far beyond what the individual looked likely to be able to afford, and then offered a discount. Even the discounted prices could be in the region of $1,000. Sometimes, people were richer than they looked – if they accepted the first estimate, their case would turn out to have ‘complications’ requiring further treatment and further payments.

Chamley’s advertisements made much of the fact that his cures involved ‘No knife or pain’, but the health investigators discovered that knives and pain were still very much part of the proceedings. As in the case of Mrs Nevin, Chamley cut out any lumps and poulticed the wound. Mercifully, he did use anaesthetics, but the operating conditions were far from aseptic. If the patient did not really have cancer and avoided infection, they had a chance of healing, albeit with scars. If the disease was cancer, it would inevitably return – but good luck getting any further assistance from Chamley.

The investigators faced numerous obstacles, given that Chamley was a qualified doctor and had plenty of money for legal representation. In the end, the Post Office Department issued a fraud order preventing Chamley and his company from using the mail – and without his ‘scare letters’, he was unable to continue his business in St Louis. His solution was to transfer to his existing Chicago practice and carry on as normal.

Chamley was no kinder to his own family than he was to the strangers he scammed. Join me next week, when I will delve into his dramatic personal life, and reveal more about the fraudulent schemes once described by the Washington post office as ‘a more sinister parasite on the community than the dread disease which Dr Chamley offers to “cure”’.2

HistMed Highlights

MUSEUMS: Up Close and Medical, 14 October. Museums from across London will gather at the Museum of the Order of St John to share their fascinating handling collections and medical-themed activities. 11am-3pm - drop in any time at Chapter Hall, St John’s Gate, London EC1M 4DA. All ages welcome.

TALK: Glimpses of Grisly Justice: The Bizarre Beginnings of Victorian Forensic Science, 14 October. Crime historian Angela Buckley looks into the ground-breaking work of the pioneers of forensic investigation. 1.30pm, The Dissenters’ Chapel at Kensal Green Cemetery, £12.

PODCAST: Poor Historians Podcast discusses the Tuskegee and Guatemala syphilis experiments of the 20th century, which cast ethics aside at the expense of minority communities.

RADIO: Best Medicine continues on Tuesday 10 October at 6.30pm - this funny and fascinating panel show brings together comedians, doctors, scientists and historians to celebrate medicine’s inspiring past, present and future.

BOOK: Plague-busters! Medicine’s Battle with History’s Deadliest Diseases by Lindsay Fitzharris and Adrian Teal is out on 10 October. Aimed at children age 8-12, this colourful book explores the scary symptoms, kooky cures and brilliant breakthroughs in humanity’s fight against disease.

German A Jordan, M.D., ‘The Illegal Practitioner, Fakers and Charlatans’, American Journal of Public Health, September 1917.

Deseret Evening News, 4 May 1916.