A vortex of suspicion: the 1927 Channel swimming hoax

Dr Dorothy Logan got into 'an awful mess' when she falsely claimed to have swum the English Channel.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

October was late in the season for attempting the 21-mile swim across the English Channel. The biting cold water and chance of storms exacerbated the danger of this gruelling challenge, and only the tough – or foolhardy – would take the risk.

On the tenth of that month in 1927, a woman described by one newspaper as a ‘hefty young lady doctor’1 entered the water at Cap Gris-Nez in France and emerged at Folkestone in England the next morning. Her time of 13 hours 10 minutes beat the women’s record, which had been set by American swimmer Gertrude Ederle at 14 hours 39 minutes the year before.

Something, however, was amiss. Within a few days the truth came out that it was all a hoax – and the swimmer faced repercussions she hadn’t bargained for.

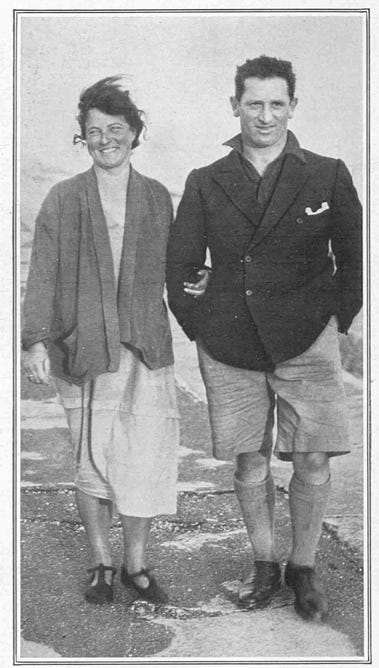

Dr Dorothy Cochrane Logan (1888 – 1961), a graduate of the University of London (MB 1912, MD 1915), was a Harley Street obstetrician and gynaecologist who also held the post of Medical Officer in Charge of the women’s gonorrhoea department at King’s College Hospital. To avoid any impact on her career, she used the name Mona MacLennan (often reported as MacLellan) for her competitive swimming. Her real identity quickly came to light after her first unsuccessful Channel attempt in 1926 – she tried to evade reporters’ questions by claiming she was the secretary of a Harley Street specialist, but it became an open secret that she was indeed Dr Logan. In August 1927, she joined a ‘mass attack’ on the Channel – five women and two men set out on the same day, but none succeeded. Logan remained in the water the longest – for 14 hours – but with a long way to go, her trainer, Horace Carey, persuaded her to stop.

The vogue for Channel-swimming made for high-profile news stories. On 7 October 1927, Mercedes Gleitze became the first British woman to succeed and was feted as a ‘Channel heroine’. But she could only enjoy her triumph for a few days.

Channel swimming had no governing body or independent verification – provided someone swam to shore and said they had gone the whole way, that was good enough for the press and the record books. Logan and Horace Carey believed that regulations should be established and umpires appointed to prevent any Tom, Dick or Harry self-declaring a successful crossing and bringing the sport into disrepute. They aimed to show how easy it was to fake the results.

Logan set out secretly for France in the fishing boat Dayspring, with Carey on board plus Lieutenant Commander L S M Adams, RN Rtd. and G H Woodward as her pilots. The crossing gave her terrible sea sickness but after a short rest she commenced her swim from Cap Gris-Nez at 7.40pm. Conditions started off favourable, but the water was extremely cold and became choppy as the night wore on. Logan later described her journey in heroic terms:

As it got light, I saw the cliffs of England in the haze, and although I kept swimming hard I did not seem to get any nearer. I was becoming discouraged, and began to think that I should have to give up without accomplishing my purpose. In fact, I suggested to those in the boat that I had better give up. They persuaded me to stick to it, however, telling me that the tide would eventually turn in my favour and take me shorewards.2

Her world-beating speed and the fact she was ‘one of the small band of brilliant women who have not only qualified as doctors, but who have made good in several spheres of medical practice,’3 completely overshadowed Mercedes Gleitze’s achievement. Logan received a prize of £1,000 from the News of the World, which had offered this to the first British woman to break Gertrude Ederle’s record.

What the News of the World did not know was that Logan had sat in the fishing boat for nine of the 13 hours. She had not expected to win any money, and later claimed she did not realise that signing an affidavit to collect it would have legal repercussions. The celebratory press coverage was getting out of hand and she decided to own up and return the prize just a week after the swim. At a press conference she reportedly said:

I seem to gave got into an awful mess. I admit now that the method I chose was foolish, but I felt something had to be done to ensure that Channel swimming was placed on the same basis as everything else. For the past two years all sorts of scepticisms have been expressed among the coast people about Channel swimmers and their claims. It was extremely annoying and I was determined that something should be done to ensure that in future Channel records were properly authenticated and that nobody could come along and challenge them afterwards.4

Logan made it clear that she did not doubt the recent successes but as one reporter put it, ‘…she also drags into the vortex of doubt and suspicion the other ladies who claim to have accomplished the great swim.’5

Mercedes Gleitze felt compelled to perform a ‘vindication swim’ in the presence of press representatives. She did not complete it, but her fortitude and ability during the attempt made it clear that her previous accomplishment was genuine.

Dr Logan had probably assumed she could go back to work and carry on as normal after proving her point, but further trouble was in store. In November 1927, she and Horace Carey were charged with knowingly making false statements in a statutory declaration and fined £100 and £50 respectively, even though Carey chivalrousy claimed it was all his idea.

The conviction put Logan’s medical career under threat. In May 1928 she was summoned to appear before the General Medical Council, at risk of being struck off the Medical Register and losing everything.

Logan ‘conduct[ed] her own defence with remarkable ability’6 and succeeded in convincing the Council that she had already been punished enough. After deliberating for half an hour, they decided not to erase her name from the Register.

In 1929, Logan and Carey got married and had a daughter, Joan, but the relationship ended a year later and they eventually got divorced. Dr Logan continued her distinguished medical practice until after the Second World War, when she and Joan emigrated to New Zealand.

The reputational damage caused by her swimming exploits never quite left her, however. On her death in 1961 at the age of 73, the Daily Telegraph headlined her obituary ‘Channel Swim Hoaxer Dies’.7