Caught short on a long trip

Discreet india-rubber receptacles helped Victorian rail passengers survive their journey

More than a million citizens lined London’s streets one sombre morning in November 1852. Others peered from windows, having paid a premium to the householders for a superior vantage point. At last, they were rewarded with a glimpse of a huge bronze chariot drawn by twelve draft horses. It progressed slowly and reverently towards St Paul’s Cathedral, in dignified tribute to a man whose life had embodied British military and political power. This moment of national theatre formed a grand farewell to Arthur Wellesley, the 1st Duke of Wellington.

The funeral procession must have been a fine spectacle, but this Substack is not concerned with pomp and circumstance. What I want to know is – what if you were stuck in the middle of the crowd and needed the loo? Presumably some people would have no qualms about doing their business in the nearest alleyway or gutter, but I would certainly not be that uncouth and I’m sure many Victorians wouldn’t either.

Thankfully, a Piccadilly surgical instrument maker called Richard Paget anticipated this problem. In the weeks before the procession, he advertised portable urinals to ladies and gentlemen planning to attend. He did not go into detail about the design and use of the device, because:

The very serious consequences which sometimes arise from the want of these useful conveniences are too well known to be more than alluded to in an advertisement.1

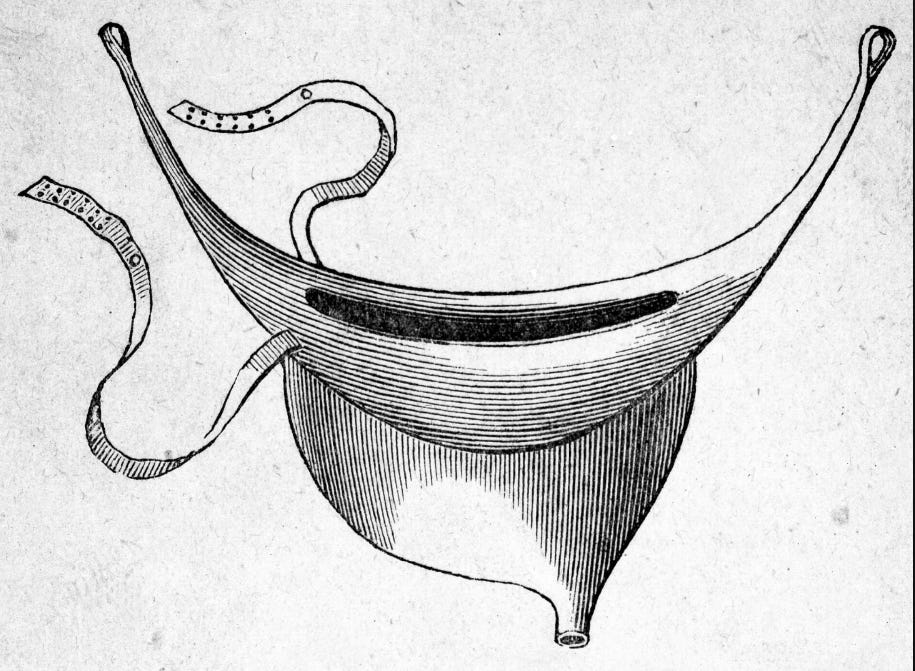

Paget’s portable urinal might have been something like a traditional bourdaloue – a small boat-shaped receptacle for discreet use under women’s skirts. But as Paget mentions gentlemen too, it’s possible that he was offering a more up-to-date contraption – an india-rubber ‘railway convenience’ like the one in this image from the Wellcome Collection.

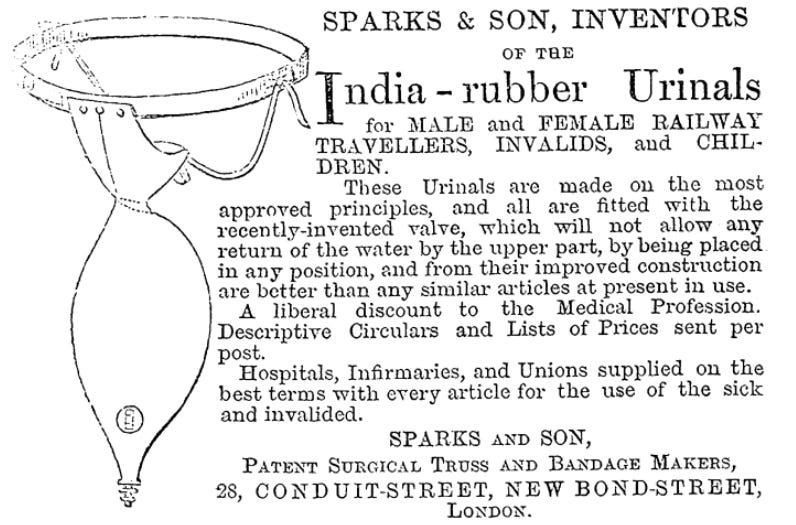

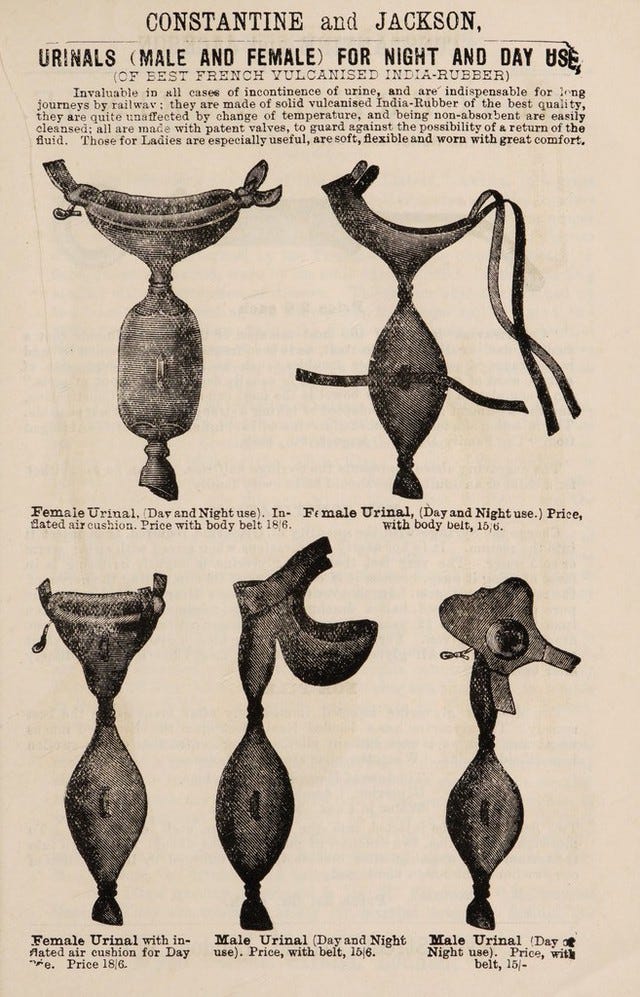

Railway conveniences or travelling urinals comprised a belt with a rubber bag underneath to catch the liquid. The basic one in this picture won a Prize Medal at the Great Exhibition in 1851, but surgical instrument makers were soon refining the design, creating specialised examples for male and female anatomy and adding valves to stop the urine escaping. As the name suggests, they were created for people likely to get caught short on trains, but they could also be useful for patients confined to bed and those recovering from surgery. This 1860 advertisement from Sparks & Son offers a discount to the medical profession and supplies public health institutions, suggesting that the same designs were used in both the travelling and medical contexts.

Some railway stations had rudimentary facilities for men but, until later in the century and the campaigning of the Ladies’ Sanitary Association, there was nothing for women – who were not supposed to be gallivanting about away from home. The ‘urinary leash’ – i.e. the inability to go out for any length of time due to lack of public lavatories – was one of the many obstructions to women’s participation in society. The idea of waddling about with a rubber sack sloshing against your thighs might not appeal, but these products offered some mitigation – however imperfect – to the absence of facilities.

Like Sparks and Son, Frederick Walters of Moorgate Street claimed to be the original inventor. His adverts – often published on the same page as his competitors’ – warned purchasers to beware the ‘many bad and useless’ imitations that had proliferated on the market.2 Walters’ design used aetherised india rubber that would not become stiff with use, and incorporated a valve to prevent the urine escaping. Ladies requiring discretion had their own private entrance to the shop and could get advice from a female assistant.

Emptying a urinal usually had to wait until the wearer could undress in private. In the 1860s, however, John Weiss of the Strand offered a ‘Gentleman’s Day Urinal’3 long enough to reach the ankle, allowing the busy man-about-town to hitch up his trouser leg, unscrew the cap at the bottom and direct the contents into some convenient outlet such as the Thames.

Frederick Walters assured customers that his products did not smell ‘if kept properly washed out’. ‘If’ is of course the operative word there. In 1879, orthopaedic surgeon Richard Davy of the Westminster Hospital showed his disgust at these devices, and also reveals that railway facilities hadn’t improved much in the past 30 years:

A rich man, probably in self defence, purchases and submits to the repulsiveness of one of those putrid urine-bags known as ‘railway conveniences’; while the bulk of suffering mankind are fain to let down the window and sprinkle indiscriminately their pent-up excretion.4

As far as I can find out, there are no surviving examples in museums – probably because the india-rubber would perish over time. Railway conveniences appear to have been ‘unmentionable’ items that people knew about but had no desire to discuss in their letters to friends, so there are few written sources. Their regular inclusion in the catalogues and advertisements of surgical instrument suppliers suggests an ongoing demand, but it must have been a relief when station lavatories became more widely available for both sexes in the Edwardian era. Needs must when the devil drives the train and these ‘conveniences’ were better than nothing – but using them and cleaning them out can’t have been very pleasant.

As author Jeoffrey Spence put it in his 1977 book Victorian and Edwardian Railway Travel Through Old Photographs:

One might visualise the hunted look which must have crept into a passenger’s eyes when wearing one of these things in a crowded compartment of mixed company, when he had come to the conclusion that it must serve its purpose.5

Thank you for reading! It’s free to subscribe to The Quack Doctor, but if you enjoy my work and would like to contribute a small token of appreciation, please visit my Ko-fi page. Thank you!

Advertisement, The Morning Herald, 16 November 1852.

Advertisement, The London and Provincial Medical Directory, 1860.

John Weiss & Son, A Catalogue of Surgical Instruments, Apparatus, Appliances etc., 1863.

Richard L Davy, ‘Abstract of a lecture on the surgical aspect of our present mode of railway travelling,’ Surgical Lectures, delivered in the Theatre of the Westminster Hospital, 1880.

Jeoffrey Spence, Victorian and Edwardian Railway Travel Through Old Photographs, 1977.