Chemical warfare against the common cold

Could the substances used to kill enemy troops have a healthier application in peacetime? Unfortunately not.

In the aftermath of the Great War, the US Chemical Warfare Service did not enjoy the heights of popularity. The cruelty of gas weaponry and its use by the Germans against allied troops had appalled the public, and CWS chief General Amos Albert Fries (1873-1963), was fighting to keep the service operational in the face of widespread opposition.

A PR boost was needed, and an interesting phenomenon observed during the influenza pandemic of 1918-20 had the potential to provide one.

Workers at the CWS’s Edgewood Arsenal, northeast of Baltimore in Maryland, came down with the flu in huge numbers – the on-site hospitals overflowed with sick people. Very few, however, who worked in the chlorine gas plant were affected. Could this mean that chlorine prevented the deadly Spanish Flu?1

In 1922, Fries saw the chance for a great public relations coup. He appointed Lieutenant Colonel Edward Bright Vedder (now better remembered for establishing that beri-beri is a deficiency disease and for synthesising its preventive, thiamine) to head up further investigations.

After studying the disinfectant properties of chlorine against bacteria on agar plates, Vedder and his colleague Captain Harold P Sawyer started work on patients suffering from respiratory infections, including colds. The subjects sat in an enclosed chamber for one hour, breathing in a concentration of 0.015 micrograms of chlorine per litre of air.

In a paper published on 8 March 1924, Vedder and Sawyer tabulated 931 cases treated with chlorine.2 They classed 71.4% as 'cured' and 23.4% as 'improved'. This they attributed to chlorine's bactericidal action, to its irritation of the nasal passages causing increased production of mucus, flushing the pathogens away, and to increased migration of white blood cells to where they were needed.

Vedder, a distinguished and conscientious scientist, was circumspect about his results, but the CWS needed a big announcement to promote its efforts for the good of humanity. When, in May 1924, Fries managed to arrange for President Calvin Coolidge to have chlorine treatment for a condition variously reported as a cold or as ‘rose fever’, the story was a hit with the newspapers and the public.3 Coolidge spent 45 minutes in a sealed chamber, breathing in a low concentration of chlorine gas. By the next day, his cold had become so bad that he had to cancel his official engagements, but after two more treatments he was well again. A cold getting better after three days? Who would have thought it?

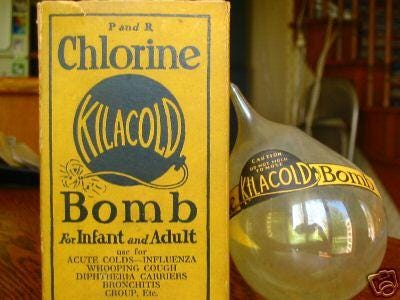

Chlorine chambers briefly became the first resort in the battle against bunged-up noses. Their popularity also spawned commercial products for home use, such as the 'Kilacold Chlorine Bomb'.

The Kilacold bomb was a teardrop-shaped glass ampoule containing 0.35g of chlorine gas, made by Richard & Price of San Francisco. The patient had to break the end off to allow the gas to permeate the air of a closed room and, according to the advertising, their cold would disappear within an hour. The treatment was also promoted for flu, whooping cough, croup, bronchitis and for diphtheria carriers, but was not recommended for people with asthma.

In 1926, the product was rebranded as the ‘P & R Chlorine Bomb’. A few years later, 11 cartons of the bombs were seized at Portland, Oregon, and condemned as misbranded because the packaging stated that the contents were ‘Absolutely harmless’ and ‘positively not poisonous in any way to the human system.’ 4 When no one came forward to claim the consignment, the FDA ordered its destruction.

Chlorine treatment also came under criticism from the New York Board of Health, whose own experiments did not show significant results. They pointed out that most colds got better anyway. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials were not yet the norm and so Vedder and Sawyer had not used a control group to show whether the chlorine treatment was an improvement on existing medications. Further experiments by Professor Harold S Diehl at the University of Minnesota5 showed that most people recovered within a week regardless of whether they had chlorine, other medications or nothing.

The chlorine treatment faded away as quickly as it had emerged, partly because the Chemical Warfare Service had moved on to other things, such as the development of insecticides and the use of tear gas for crowd control – particularly in the event of a Communist uprising, which the strongly anti-Communist General Fries believed was on the cards.

Political motivations contributed both to the beginning and end of this short-lived therapy, and humanity's thousands of years of affliction with the common cold continued unabated.