Christmas in the Victorian hospital

In 1890s London, hospital staff did their best to give patients a bit of Christmas cheer.

‘Father Christmas, with a flowing white beard, and ruddy and genial of countenance, arrayed in the typical crimson fur-edged cloak, starts on his rounds of the wards.’1

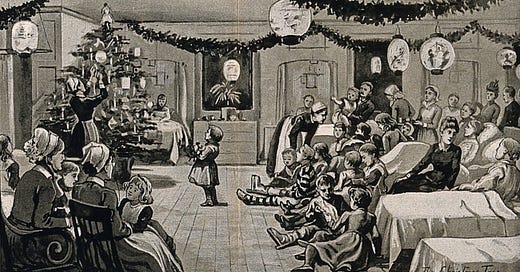

The role of Father Christmas at the London Hospital in the 1890s fell to one of the house surgeons. He was accompanied by a pair of medical students, who gamely dressed up as Pierrots to help distribute presents to the patients. The children received toys, sweets, and a shiny new penny each, while adults opened practical gifts such as scarves, socks and hats knitted by the nurses throughout the year.

Christmas Day could be an early start - 6am carol singing followed by a worship service was not unusual, and in 1894, the Echo newspaper reported that ‘Shortly after four o’clock in the morning, the full staff of nurses, each carrying a coloured lamp, made the round of the wards and sang carols.’2 Getting any sleep in hospital is difficult at the best of times, so I suppose you might as well have a sing along.

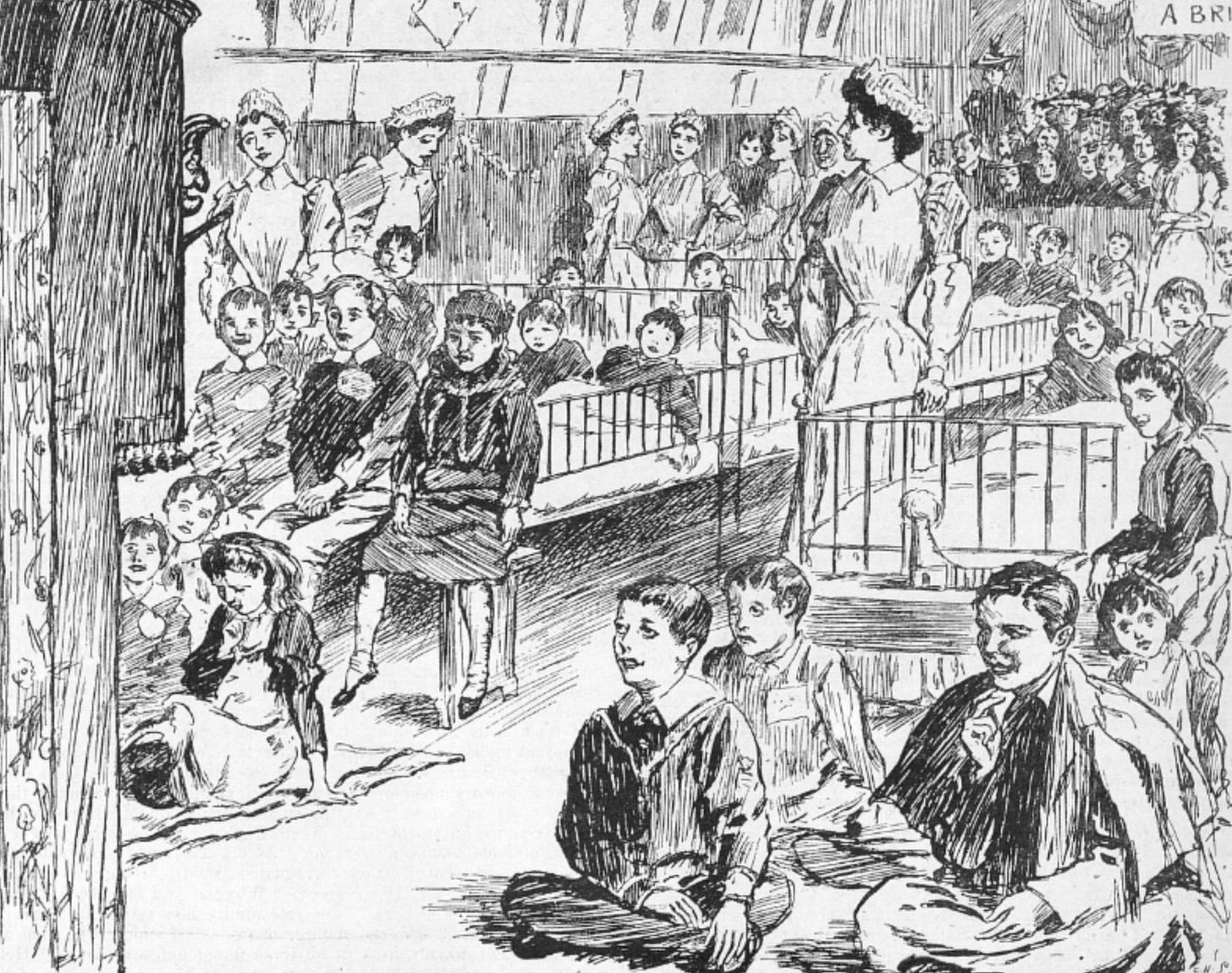

Those with a good appetite would sit down at noon to a roast beef dinner followed by a plum pudding that was carried around the ward flaming with brandy and topped with holly. In the afternoon, the nurses wheeled the beds to one end of the ward, while the other end became a stage for sketches and music hall songs courtesy of the medical students. These students repeated their show in each ward, which meant they were performing non-stop for about six hours.

The custom of Christmas festivities began to take hold in London’s hospitals during the 1860s, with the encouragement of the British Medical Journal, which commended St George’s for introducing the tradition of a Christmas tree. Decorating the wards was an important part of the celebrations, and the nurses used evergreens, flowers, flags and cotton wool to create a cheerful scene.

At Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in 1896, around 200 of the poorest long-term outpatients were invited to a Christmas party. After a delicious meal, they and their parents walked through ‘a long arcade of Chinese lanterns, fairy lights, palms and evergreen, and heaps of cotton wool snow, to the North Room, passing a kind of blue grotto in which the many friends of the institution were assembling.’ There, they listened to a concert by Essex & Cammeyer’s Mandolin, Banjo and Guitar Orchestra, comprising 15 volunteer musicians who gave their time to perform at several hospitals that year. The highlight of the event was for the children to choose a present from a Christmas tree festooned with ‘dolls, trumpets, picture-books and Noah’s Arks.’3

Hospitals with adult patients generally allowed the men to smoke on Christmas Day, sometimes even giving them a pipe and some tobacco as a gift. While this must have made breathing more difficult for some patients, it cheered up those who had been missing the pernicious weed. Women were more likely to receive fruit such as an orange, though in the women’s wards of the London Hospital in 1897, ‘pinches of snuff are interchanged with garrulous conviviality.’4

Although the focus of the hospital Christmas celebrations was to make life a bit more bearable for the patients, staff were not forgotten. In 1894, the nurses of St Bartholemew’s Hospital and their guests were invited to watch a comedy farce performed by the medical students and junior doctors. The play, Thomas Edgar Pemberton’s Freezing a Mother-in-Law, involved a plot to test a newly discovered liquid that could be injected into someone’s ear to put them into a state of suspended animation. A young man discovers that his prospective mother-in-law, Mrs Watmuff, is the intended target, and although they have not always seen eye to eye, he sets out to warn her and thwart the scheme. In a nod to Shakespearean tradition, all the parts were played by men, and surgeon Harry Brownlow was reportedly the star of the show as Mrs Watmuff.5

In most hospitals, the festivities and gifts were funded by charitable donations from local people, who wanted to do what they could to bring some Christmas cheer to those facing illness and injury. For patients whose home lives were characterised by drudgery and often downright squalor, Christmas in the Victorian hospital was a more attractive prospect than we might now expect. Indeed, an article in the Pall Mall Gazette by ‘a Mere Layman’ in 1897 suggested that people were keen to be admitted to the London Hospital at this time of year, ‘for is it not better to be entertained royally in a comfortable ward than to shift for yourself in the destitution and cold of a “mean street” in Whitechapel?’

Thank you!

Thank you to everyone who has read and subscribed to The Quack Doctor since I started posting here in August. I will be having a couple of weeks’ break over Christmas and New Year, and will be back on 11 January with more tales from medicine’s past.

In the meantime, I wish you a joyful festive season and the best of health in 2024.

From The Quack Doctor archives

The Instra Warmer

Perfect for these chilly winter nights, the Instra Warmer was a portable heating device patented in 1896 by the 12th Earl of Dundonald, who used the motto ‘Warmth is Life’ to promote it. Available in either an embossed silver plated design or a plain tin version, it contained a replaceable fuel cartridge that the wearer had to set light to. It could then be kept in the pocket to ward off colds, neuralgia, rheumatism and even toothache.

Pall Mall Gazette, 29 December 1897.

The Echo (London), 26 December 1894.

Daily Telegraph, 29 December 1896.

Pall Mall Gazette, 29 December 1897.

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 13 January 1894.