Defeating the death microbe

A story did the rounds in 1895 that a newly discovered bacterium was the only thing standing between humans and immortality.

In May 1895, a low-key but intriguing advertisement appeared in British local newspapers.

What could this ‘death microbe’ be? Did it refer to the lethal pathogens such as anthrax and tuberculosis that had been identified within the past two decades? Announcements of newly isolated bacilli regularly reached the general population through the press (in 1889, someone in Paris even claimed to have found one for smallpox, which is now known to be a virus). It was through the same medium that patent medicine sellers capitalised on the idea that science had the key to ending disease.

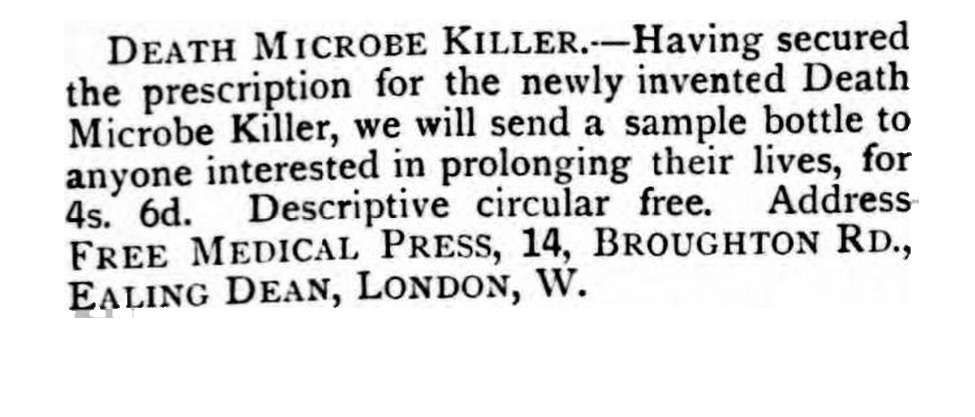

The best known germ-vanquishing remedy, Radam’s Microbe Killer, arrived in the UK from the US in 1889, using a striking visual metaphor of Death succumbing to the medicine’s might. Deadly bacteria made inroads into literature too – just a year before the above advert was published, Rudolph de Cordova’s short story The Microbe of Death featured a murderous doctor who deliberately infected his victim with anthrax.

With microbes in the cultural ether, it is not surprising that advertisements referred to them, but it turns out that the one at the beginning of this article was promising a lot more than a cure for TB.

A story circulated that one Dr Wheeler of Chicago had discovered another bacillus. The new bug wasn’t a germ of disease, however; it was the ‘grand master microbe of all’ – the very embodiment of Death itself. Even if you were lucky enough to avoid disease, murderers and runaway omnibuses, you would at last succumb to the Death Microbe. If science could find the means to destroy it, people could potentially live forever.

According to early reports, Dr Wheeler had experimented on animals and discovered that once the death bacillus was eliminated, no known disease could take hold. He was developing a treatment that would literally kill Death.

The fact that humans are still popping their clogs willy-nilly is sufficient proof that he didn’t succeed, but for a few weeks his supposed findings attracted tongue-in-cheek commentary about people’s ability to put up with immortality.

It’s fair to say that the newspapers did not take Wheeler’s discovery very seriously. The population, speculated one commentator, would grow so quickly that many would be pushed off the land masses and forced to roam the sea in houseboats. Undertakers, gravestone masons and life insurance companies would go out of business and, without the prospect of eternal hellfire to keep our behaviour in check, morality would go to the dogs. Another problem was that people would still grow old; the comic periodical Fun asked:

What are we to do in 2,500 A.D., with all the toothless grumbling old crones occupying not only the chimney corners, but every easy chair in the country?

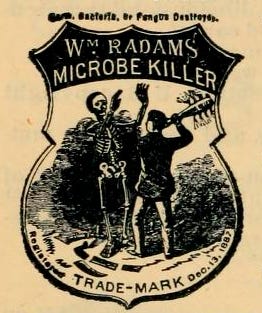

Whether the ‘Death Microbe Killer’ adverts attracted any customers, it is difficult to tell. They did, however, inspire artist Archibald Chasemore (1844-1905) to create a science-fiction comic, Extracts from the Diary of the Last Man, which appeared in the 22 May 1895 edition of Judy: The London Serio-Comic Journal.

The hero responds to the ad and buys a huge quantity of the Death Microbe Killer, which allows him to survive for thousands of years. He goes through 402 marriages - keeping the medicine a secret from all his wives - before deciding to ‘remain a widower for a century or so, just for a bit of a change.’

The Death Microbe Killer eventually runs out in the year 20,095, and the character’s implied demise comes at the pincers of a gigantic futuristic crab.

The discovery of the death microbe did not have a lasting impact on medicine, no doubt because it was completely made up. As The Spectator noted, the story originally appeared on 1 April, and was probably a prank put out by Dalziel’s News Agency. Because papers tended to lift interesting items from other publications, it continued being replicated after April Fool’s Day and the fictitious Dr Wheeler enjoyed fleeting fame before sinking back into non-existence.

A similar story popped up again the following year, with the microbe now taking the dignified name of bacillus mortis, but the means of vanquishing it remained elusive. Perhaps that was for the best. As one journalist pointed out, such a remedy could well be redundant:

…in a world where three score years and ten have often been found long enough to drink the cup of existence to the dregs.

New on the to-read shelf

Pathogenesis: How germs made history by Jonathan Kennedy

Out in paperback 4 April 2024, ISBN 978-1804991893

Dr Jonathan Kennedy argues that germs have shaped humanity at every stage, from the first success of Homo sapiens over the equally intelligent Neanderthals to the fall of Rome and the rise of Islam. How did an Indonesian volcano help cause the Black Death, setting Europe on the road to capitalism? How could 168 men extract the largest ransom in history from an opposing army of eighty thousand? And why did the Industrial Revolution lead to the birth of the modern welfare state?

The latest science reveals that infectious diseases are not just something that happens to us, but a fundamental part of who we are.

HistMed Highlights

WARTIME MEDICAL STUDENTS: 🪖 In April 1945, 96 London medical students volunteered to help at the newly liberated Belsen concentration camp. On arrival, they set about looking after and delivering food and water to the 45,000 starving inmates. At the end of four weeks the students flew back to Croydon airport, returned to their medical schools, and never met as a group again. In his lecture The Role of London Medical Students in the Relief of Bergen-Belsen in 1945, Professor Stephen Challacombe tells their story. 6pm BST, 10 April 2024, Apothecaries Hall, London EC4V. Tickets £10 members, £20 non-members. Book here.

EMPIRE AND EDINBURGH:⚕️A two-day international conference (online and in-person) titled Race, Empire and the Edinburgh Medical School brings together historians, heritage professionals and other scholars whose research investigates the Edinburgh Medical School’s history from the perspectives of race and empire. 18-19 April 2024, Main Library, University of Edinburgh. Registration for either in-person or online attendane is free - register here.

CYFARFOD Y GWANWYN: 🦴🌿Cymdeithas Hanes Meddygaeth Cymru/The History of Medicine Society of Wales is holding its Spring Meeting at the Imperial Hotel, Llandudno, on 19 April 2024. This whole-day conference includes talks on haemophilia, bonesetting, Cardiff’s 19thC doctors and the Welsh folk medicine practice of torri’r llech. Attendance by arrangement with the secretary: djtwebster@doctors.org.uk

HEAD TO TOE: 🦶🏽👂The Physician’s Gallery at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh concludes the ‘Head to Toe’ series of its ongoing podcast, Casenotes, with a look at the history of feet and shoes. The hosts explore why ancient Egyptians had two left feet, why witches had flat feet, why ancient Greeks had one foot longer than the other and what you’d do with a ‘foot bag’. Listen on Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

Sources: