Dr Kane's radium swindle

Harry Hubbell Kane conned $10,000 out of a patient desperate for a radioactive cure.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from the history of medicine and related themes.

It’s free to subscribe, but if you enjoy my work and would like to contribute a small token of appreciation, please visit my Ko-fi page by clicking the button below. Thank you!

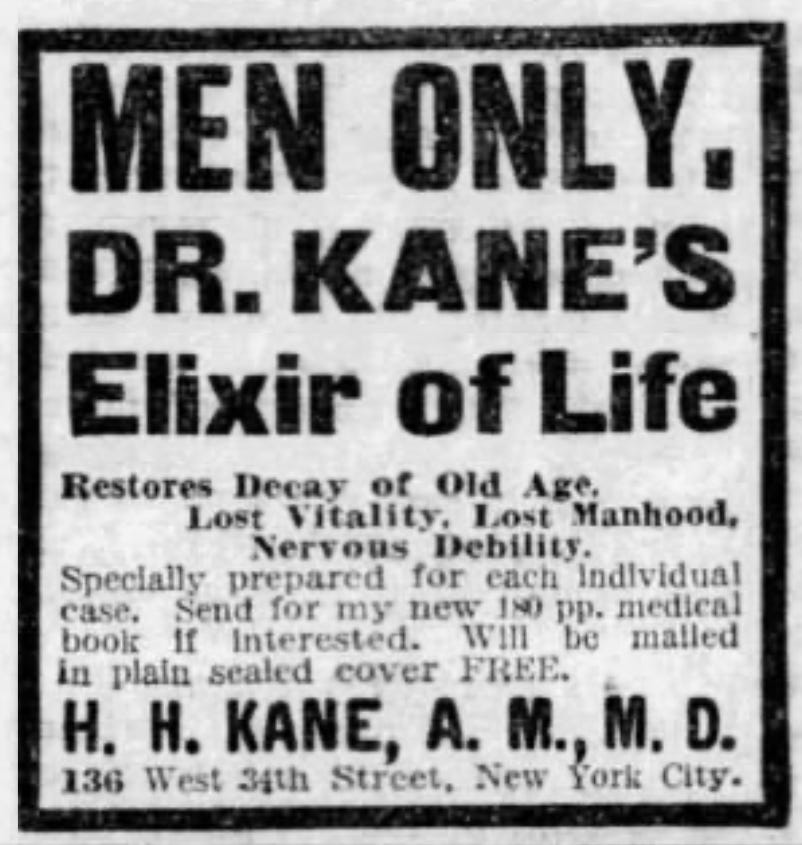

After the demise of the Scotch Oats Essence Company, Dr Harry Hubbell Kane moved on to restoring the manhood of gentlemen suffering from prostate enlargement, varicocele, hydrocele, bladder issues, ‘lost powers’ and other potentially embarrassing conditions.

This time, he did not distribute a patent remedy but offered treatment at his Civiale Agency in West 34th Street, NYC, and later at the Deslon-Dupré Clinic in Boston. A young man named John A Grady, initially hired to look after Kane’s dogs and horses, was promoted to ‘Medical Superintendent and Consulting Electrician.’ He pops up again later in the story, as we shall see.

Although advertisements invited patients to send off for a book of clinical lectures explaining how Kane offered ‘a positive cure without cutting,’ some testimonials referred to operations – which had, of course, been a complete success.

The Boston Journal of Health shed light on the real methods of ‘that prince of humbugs’ in 1889.

The ‘treatment’ at first consisted of six courses of ‘soluble crayons’ for ‘sexual and urinary diseases,’ and included a ‘pre-marital course’ and a ‘tonic regulator.’ To these were added a developmental (sic) lotion, a ‘Van Buren lotion,’ an ‘Invigorating lotion,’ a ‘tissue sensitans’, a ‘tissue sedativus’, an alleged electric belt, an instrument for varicocele, etc., etc.1

The Journal also censured Kane’s practice of employing young women to send out the junk mail, which brought them into contact with booklets full of explicit illustrations and ‘studied lying and beastliness.’

The men replying to the advertisements with details of their medical worries got a standard diagnosis and a request to send money for their prescription. After further correspondence and additional treatment recommendations, they would receive a C.O.D package containing products and another bill for $35 or more. Many realised they had been swindled, but accepted the parcel out of embarrassment and fear that their letters could be made public.

In 1893, Kane finally divorced his wife Mattie on the grounds of her infidelity. A sensationalist account in the Cincinnati Enquirer related how he employed Fuller’s Detective Agency of New York City to gather evidence. The sleuths observed Mattie Kane checking in to a Long Island hotel with a young man thought to be racehorse trainer Billy Brandon (though it turned out not to be him).

On another occasion Fuller’s worked in co-operation with the Grannon Detective Bureau of Cincinnati to find her staying with her lover at St Nicholas’ Hotel in the names of ‘J S Wade and wife’. Captain Grannon tried to draw her out with a message claiming to be from an old friend who had just arrived in town, but she saw through the ruse and caught a train back to New York, later deciding to get out at Philadelphia due to an argument with her companion.

‘Mrs Kane is a very handsome woman,’ said the Enquirer, ‘apparently about 30 years of age. She is a perfect brunette and possesses a great amount of style and chic that would attract attention anywhere.’ 2

The divorce decree came through on 27 July 1893; the next day, Mattie married John A Grady – Kane’s former stable hand and ‘medical superintendent’ – and apparently lived happily ever after. Harry Kane married Agnes DeGroff in 1895. He became heavily involved in the sport of harness racing, regularly winning prizes with his top-quality horses, and serving as president of the Road Drivers’ Association – presumably with a new stable hand.

Meanwhile, his medical practice evolved to incorporate the very latest scientific developments. In 1898, Marie and Pierre Curie discovered radium, and its powerful – but unregulated – effects were immediately applied to medicine. Here I can highly recommend Past to Present with Lucy Jane Santos for the fascinating history of radioactive cures!

Dr Kane’s sanatorium on West 34th Street continued to offer treatment for prostate and bladder issues, and in 1904 he promised that his new ‘Elixir of Life’ had properties ‘as wonderful as those of radium’. Sometimes, however, only radium itself would do – and that was what he told John McCullum, a carpenter from Mount Vernon who was in the early stages of kidney disease.

McCullum only found out about his condition when undergoing a medical examination for life insurance. He wanted to protect his $10,000 savings for the sake of his 10-year-old son, whose mother died in 1903. It’s quite possible that he told Kane this backstory, causing the dollar signs to spin in the doctor’s eyes.

Kane and his accomplice, William H Hale, gave McCullum regular hypodermic injections that made him feel worse. He also had an ‘x-ray treatment’ that involved the doctors flashing red, green and blue lights at him. They then told him that nothing but radium – expensive as it was – could save his life.

The frightened Mr McCullum’s savings dwindled in return for regular bottles of radium solution. Eventually, when he had nothing left, Kane and Hale informed him that they had paid $13,000 up front to get hold of the radium, and he owed them the $3,000 balance.

This greedy mistake led to their downfall. The County Medical Society heard of the case and sent in a female detective to pose as a wealthy widow willing to furnish the money. She claimed to have taken a particular interest in McCullum’s plight and would be able to remit the funds after 1 January 1905. Kane handed over the next bottle of medicine – giving the Medical Society the chance to analyse it and confirm that it contained ginseng and strychnine, not radium.3

In one sense, this was good because at least McCullum wasn’t getting radiation poisoning. On the other hand, Kane had conned his patient out of $9,870 under false pretences. He went to prison for four months – the sentence would have been longer, but he did pay McCullum back the full amount. William Hale, who had a previous conviction for practising medicine without qualifications, got eight months.4

The prison experience took its toll on Kane and, shortly after his release, he developed tuberculosis. He died in 1906, with a brief obituary in The New York Times remembering him as ‘the horseman who invented a radium swindle which put him in jail.’5

You can find more tales of patent medicines, dubious devices and the people who peddled them at my website, thequackdoctor.com