'Eager to be up and doing': the highs and lows of coca wine

Victorian nervine drinks contained a potent combination of alcohol and cocaine.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from the history of medicine and related themes.

It’s free to subscribe, but if you would like to make a one-off contribution to the coffee supplies that keep me going, please go to my Ko-fi page here. Thank you!

A version of this article has previously appeared on thequackdoctor.com

John Michael Smith is one of those fleeting figures who cross history’s pages when they get into trouble and then disappear, leaving only a hint of a life where destitution is more prominent than criminality. At the age of 11 he lived in Lodge Lane, Derby, with his mother and siblings. His dad died in 1909 and, a year later, after a policeman found John in a neglected state, the NSPCC induced the family to go into the workhouse. They immediately decided to leave, and in September 1910, John got caught stealing a bottle of Hall’s Wine. The courts sent him away to Clifton Industrial School in Bristol to remove him from the bad influence of his mother, whom the NSPCC inspector considered ‘not a desirable person to have the care of him.’1

What was this elixir for which John risked his liberty?

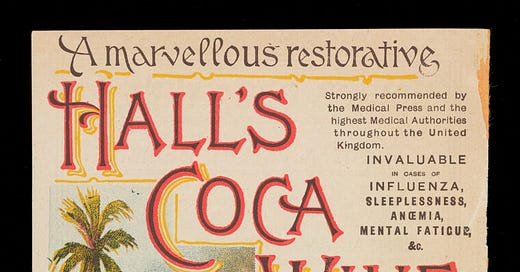

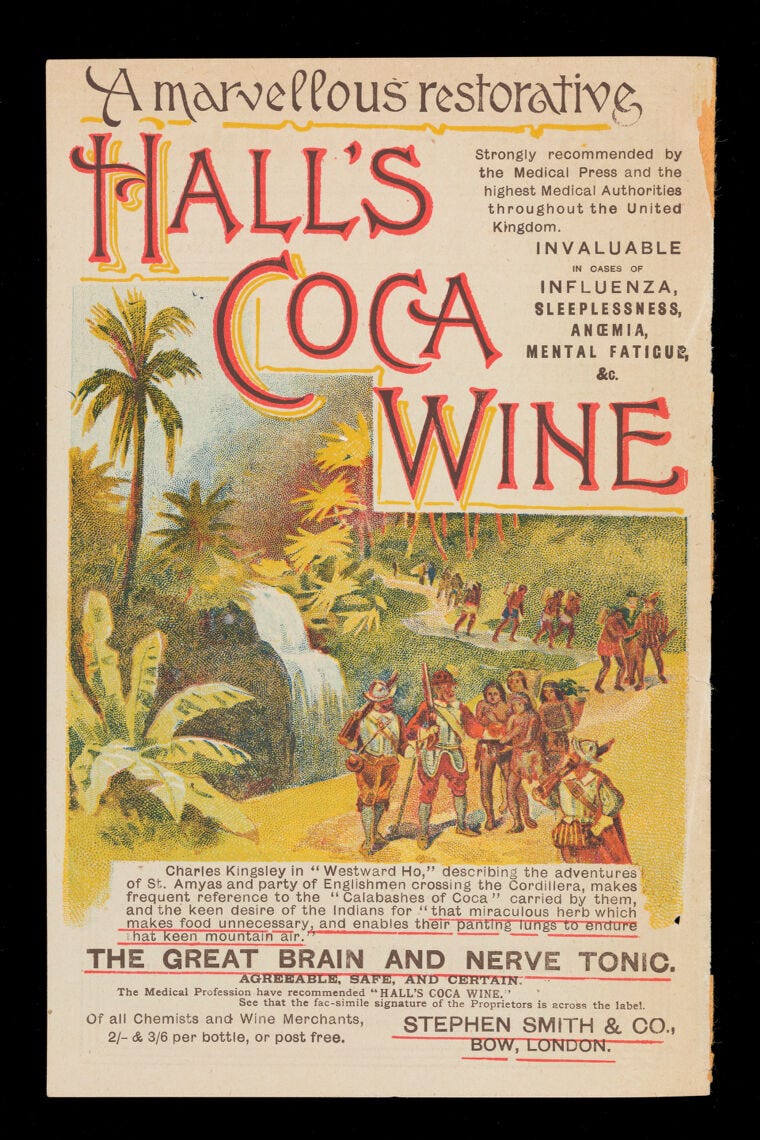

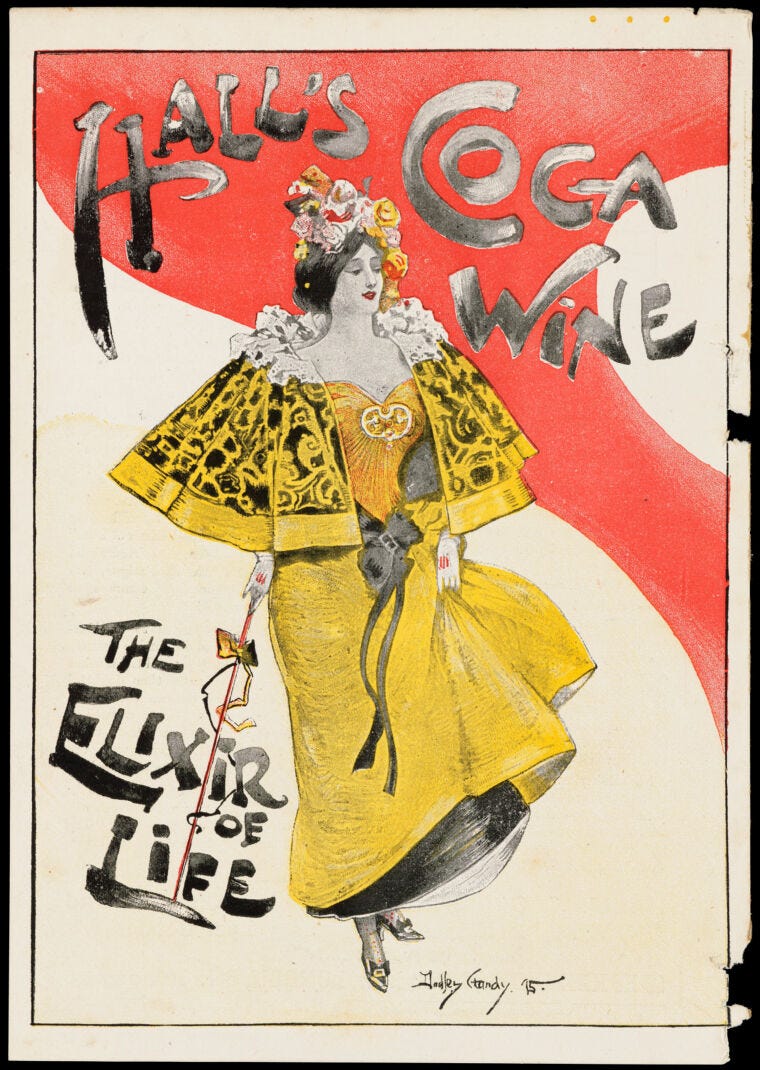

Hall’s Wine was one of the proliferation of late-Victorian ‘nervine’ drinks that contained cocaine. Others include Wincarnis, Vin Mariani, Armbrecht’s and Vibrona. Consisting of Old High Douro and Priorato port with extracts of the plant Erythroxylum coca, the Hall’s brand first appeared in 1888. In promoting it, however, Henry James Hall (trading as Stephen Smith & Co) soon discovered that he was popularising coca in general and boosting sales of inferior competitors. It was also not possible to register the words ‘coca wine’ as a trademark, so in 1897 the name changed to ‘Hall’s Wine’ – not to hide the fact that it contained cocaine but to strengthen Hall’s as a brand. Adverts claimed the wine was ideal for those times ‘When you are neither one thing nor the other’, and would restore ‘the last five or ten percent of health, without which all is dulness.’ It would make you ‘eager to be up and doing.’2

An approving write-up in The Lancet in 1892 enabled Hall to promote the wine as endorsed by the medical profession.3 Before the turn of the 20th century, however, medical journals had begun to express reservations about the unregulated sale of such products.

The BMJ’s 1897 article, ‘Coca Wine and its Dangers’ showed concerns that parents were giving the wine to their children, and that:

School mistresses as a rule have a deep-rooted belief in the efficacy of the popular drug, and give it to their pupils on the slightest provocation, in complete ignorance of the fact that they are establishing a liking not only for alcohol but for the far more insidious and pernicious poison cocaine.4

Some people, the BMJ reported, considered themselves to be teetotallers, but drank coca wine under the impression that it was good for them.

In 1909, an analysis by the BMJ showed that Hall’s brand was 17.85% alcohol. The cocaine content was tiny, and ‘barely sufficed to cause any appreciable numbing when applied to the tongue.’5

Reporting to the 1914 parliamentary Select Committee on patent medicines, President of the Royal College of Physicians Sir Thomas Barlow had no doubt that ‘the prescription of medicated wines is in some cases responsible for the starting of the drink habit, especially in women.’ An anonymous contributor to the reports warned that: ‘The devil in disguise is more dangerous than the devil with his fork and tail.’ He was referring to alcohol, not what would now usually be considered the more harmful drug.6

But did people genuinely not realise that coca wine was… well… wine? Some people were more cynical about the idea of teetotallers innocently mistaking it for a ‘temperance drink’. For one West End doctor interviewed by the Daily Mail in 1897, drinkers were finding coca wine ‘an excellent way to swallow their principles and their alcohol without endangering their reputations as total abstainers.’7

‘Remember,’ he said, ‘that it is not the cocaine that is the dangerous element.’ Perhaps young John Smith was not a coke addict at all, but just trying to gain respite from his situation in the time-honoured embrace of booze.

‘Children’s Court’, Derby Daily Telegraph, 26 September 1910.

‘When you are neither one thing nor the other’, The Illustrated London News, 30 June 1900.

‘Analytical records’, The Lancet, 9 April 1892.

‘Coca Wine and its Dangers’, British Medical Journal, 6 February 1897.

‘The Composition of Some Proprietary Food Preparations’, British Medical Journal, 29 May 1909.

Report from the Select Committee on Patent Medicines, together with the proceedings of the committee, minutes of evidence, and appendices. 1914, (414) IX.1

‘Abstainer’s awful death’ Hull Daily Mail (referring to a story in The Daily Mail), 12 February 1897.