'Give the man his finger!'

An amateur anatomist got into trouble for detaining an amputated finger.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

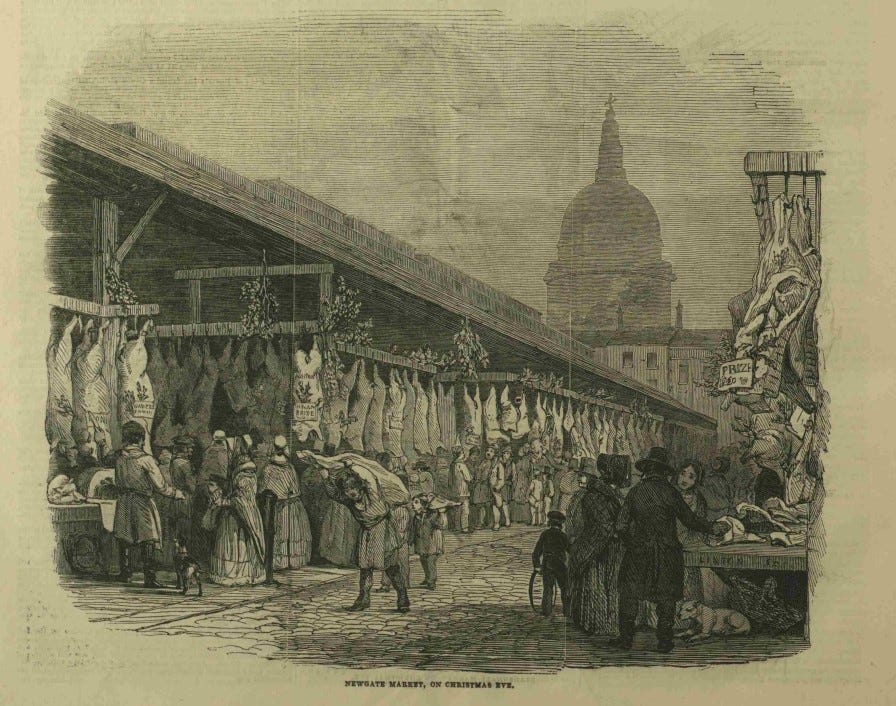

Butcher’s assistant Charles Barnard accidentally ran a meat hook through the first finger of his right hand at London’s Newgate Market in the autumn of 1824.

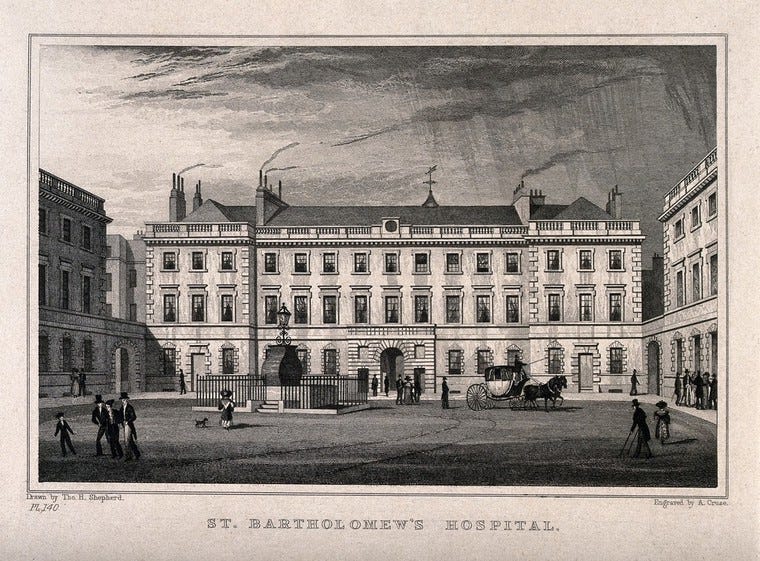

He did not seek medical advice right away, but poulticed the wound according to the instructions of poulterer James Selwood, who had ‘an itching for surgery’. In due course, mortification (necrosis) set in and Barnard went to St Bartholemew’s Hospital, where surgeon Mr Lawrence said the finger would have to come off.

William Lawrence (1783-1867), who would go on to become President of the Royal College of Surgeons and Serjeant-Surgeon to Queen Victoria, was a controversial figure who had published Lectures on physiology, zoology and the natural history of man in 1819. In it, he considered humans as a species whose characteristics could not be explained by Scripture but by science. The book’s pre-Darwinian ideas touched upon selective breeding and refuted a prevailing theory that different races were the result of climate in different parts of the world. He recognised that characteristics were inherited but did not know how this occurred. In 1822, the Court of Chancery ruled the book blasphemous and Lawrence had to withdraw it from publication.

This did not stop him being appointed surgeon at Barts in 1824, however, and Barnard was among the thousands of patients he saw in the course of his work. In his later writing, Lawrence does mention the case of a butcher’s boy ‘whose hand had been pierced by a hook, which had torn away a large triangular flap in the palm of the hand’1 but given the hospital’s proximity to Newgate meat market, the hazards of the butcher’s trade, and the different details of the injury, we can’t be sure he is referring to Barnard.

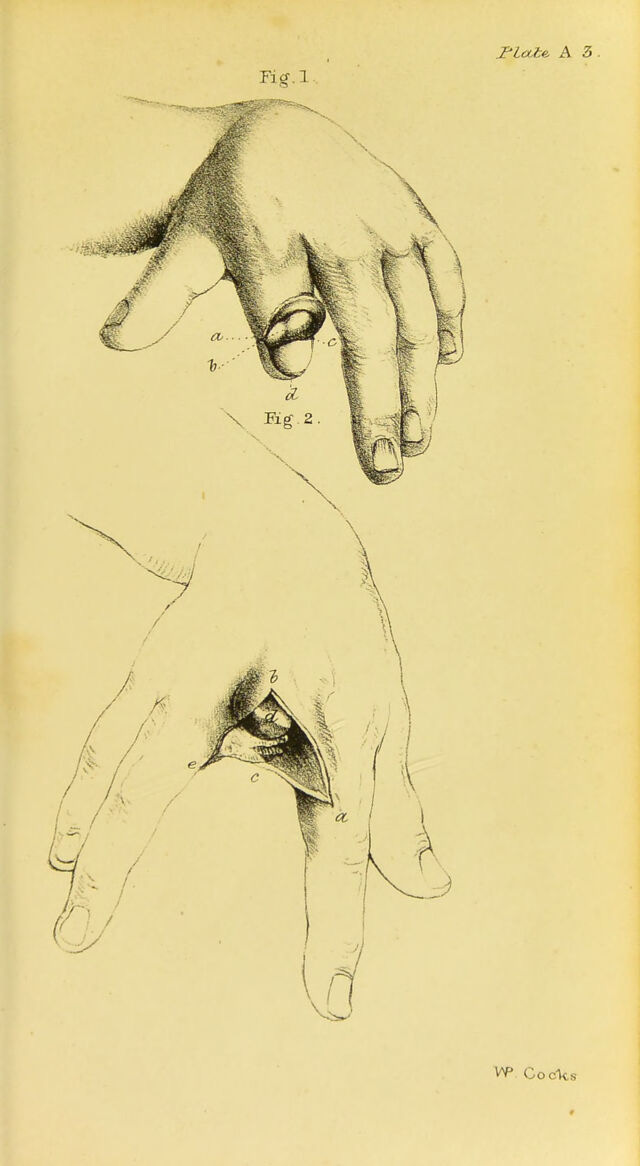

Selwood, with his surgical interest, was keen to attend the operation. The amputation of a finger at the first phalange involved creating a triangular flap of skin and using a knife to disarticulate the joint, after which the flap could be used to cover the stump. Prior to aseptic surgery and anaesthetics, there was a high risk of shock and infection – but Barnard’s procedure went well and Mr Lawrence allowed him to keep the finger for posterity. Selwood offered to take it away and prepare it for preservation under the guidance of some medical men he knew – in opposition to Barnard’s girlfriend, who believed the finger should receive a proper burial and have the funeral service read over it.

The next Barnard heard from his disembodied digit, however, was that Selwood had been challenged to eat it for a wager of 10l. Selwood refused to give it back, saying that he would rather chop it up, and word went around the market that he now intended to make it into a tobacco-stopper.

‘Poor Barnard, shocked at the idea of having his own finger pointed at him in scorn and ridicule by all the butchers’ boys in the market, now claimed its restoration.’2

When Selwood received a summons from the magistrates’ court, he realised he had entered the ‘find out’ phase of his shenanigans and packed up the finger in a parcel to send to its rightful owner.

Barnard, however, insisted on going to court, and was backed up by Alderman Venables, the magistrate, who said to the defendant:

‘But what right have you to detain a man’s finger when he wants it? Surely he has the greatest right to his own finger of anybody in the world?’

Selwood tried the perennial ‘I was only joking’ defence, but the Alderman was not having it.

‘Give the man his finger,’ said Mr Alderman Venables. ‘Where is it?’

‘I have it in my pocket,’ replied Mr Selwood; and drawing out the amputated finger, wrapped up in a piece of paper, delivered it to Barnard, who, after opening the paper and eyeing it as if to ascertain its identity, put his finger in his pocket.’

Selwood was liable for expenses, which he refused to pay. A friend settled the debt and that was the end of the matter – at least as far as the court was concerned. How much amusement the episode continued to provide in Newgate Market is not recorded, but it is likely Selwood wished he had never laid a finger on the doomed appendage.

William Lawrence FRS, Lectures on Surgery, Medical and Operative, as delivered in the theatre of St Bartholemew’s Hospital (1832)

‘The Amateur Anatomist and the Amputated Finger’, The London Courier and Evening Gazette, 4 December 1824.