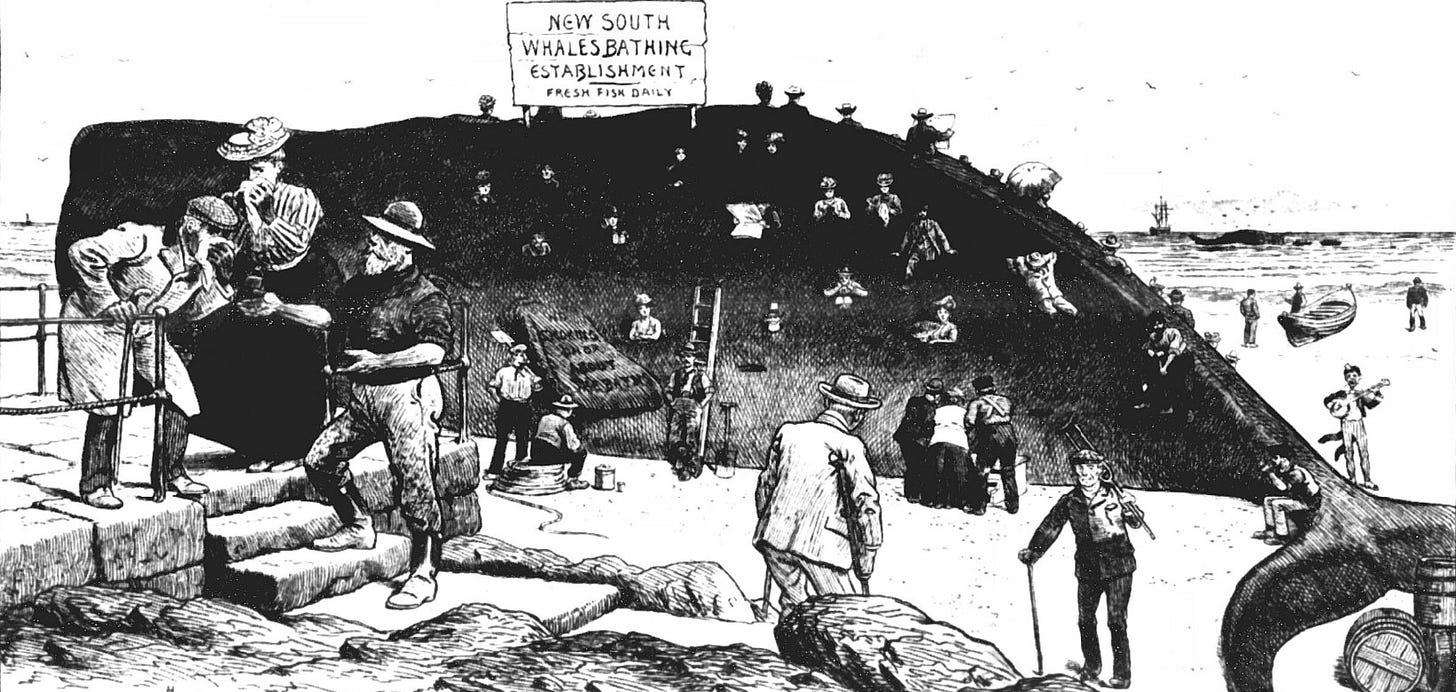

'Horrible bubbles': the whale bath for rheumatism

In New South Wales in the 1890s, people sought pain relief by immersing themselves in a rotting whale

When a 70ft-long whale carcase washed up on the beach near Bungen Headland at Newport, NSW, in 1907, it attracted attention from sightseers. Some of them, according to the Goulburn Herald newspaper, had more than a passing interest in the gruesome sight – as rheumatism sufferers, they knew from the rumours of the past ten years that the whale could be the answer to their aching joints.

‘It is found necessary,’ reported the paper, ‘to keep as much as possible to the windward of the mammal, except in those cases in which the rheumatics are especially severe, as the effluvium of blubber is not over pleasant to those in good health.’1

By 1907, the ‘whale cure’ was on its last flippers and at the time of this news report, none of the sightseers had gone so far as to climb into the carcase. In the previous decade, however, taking a bath in the decomposing blubber of a deceased leviathan was briefly popular.

‘Rheumatism’ was something of a catch-all term for conditions causing pain, stiffness, and inflammation in the joints and surrounding tissues. This would include the autoimmune disease rheumatoid arthritis, along with osteoarthritis and non-specific aches and pains. Some patients, therefore, started out with less serious conditions than others, which could explain them feeling temporarily better after trying the numerous cures advertised in the papers or recommended by friends.

The particularly unpleasant treatment that concerns us here usually took place at the whaling stations of Twofold Bay. Patients stayed at the town of Eden and, when a whale was killed and towed in, they would be rowed out to it. According to writer Louis Becke, the process involved lowering yourself into a hole in the whale, closing up the aperture so that just your head poked out, and staying there for as long as possible – a total of 20 or 30 hours, with breaks. Becke noted that workers at the whaling stations vouched for the remedy’s efficacy and claimed that none of their colleagues ever suffered from rheumatism. They believed that ‘the “deader” the whale is, the better the remedy,’ due to the gases of decomposition.

‘It is these gases, which are of an overpowering and atrocious odour, that bring about the cure, so the whalemen say. Sometimes the patient cannot stand this horrible bath for more than an hour, and has to be lifted out in a fainting condition, to undergo a second, third, or perhaps fourth course on that or the following day.’2

One story about the discovery of the cure held that ‘a gentleman of convivial habits’ had been taking an after-dinner stroll at Twofold Bay and thought it would be hilarious to jump into the giant carcase of a whale. His horrified friends tried to pull him out but:

‘The heat and smell were too great, and they retired to wait until he should come to his senses and fight his own way out. He found himself so comfortable that he did not emerge for over two hours. When he did, however, he was quite sober, and, strangest thing of all, the rheumatism from which he had been suffering for years had entirely disappeared.’3

This tale appears to have originated with the Pall Mall Gazette in the UK, and was probably just made up. The Yorkshire Evening Post called it ‘a rather tall yarn’ and opined with damning understatement that ‘the author of this story should have been born in America.’4 But although drunken high jinks probably weren’t responsible, the whale bath itself was not a newspaper invention.

The connection between whales and healing was already established among the Aboriginal people of the Twofold Bay area, who used all parts of beached whales for day-to-day purposes including medicine. Anthropologist R H Mathews described a process similar to that adopted by the white sufferers:

‘After the intestines have been removed, persons suffering from rheumatism or similar pains go and sit within the whale’s body and anoint themselves with the fat, believing that they get relief by doing so.’5

A more detailed account of the experience comes from a writer using the pseudonym ‘Traveller’ in The Bulletin (Sydney) in 1896.6

‘Traveller’ and his friend Johnson – both rheumatism sufferers – laughed at the whale cure at first, but increasingly came round to the idea and set out for Eden to give it a go. When Traveller arrived at the whaling station, he found Johnson already there, and ‘to make the awful smell less horrible (as if that was possible) he was singing at the top of his voice.’

Traveller – who was in a lot of pain and fairly immobile – was carried to a hole in the whale and instructed to work himself down into the flesh until the pressure became too great to endure.

‘I stood there for an hour and 20 minutes, and just near me was my friend Johnson, who really seemed to enjoy the situation and kept shouting smart remarks across the rib that separated us. But for his company, I could not have stood it ten minutes.

‘The smell and heat were hardly bearable. The whale had been dead about forty hours, and had started to decompose, and the whole time we were sitting and standing there great blasts of gas and horrible bubbles would gush out around us and make our hair stand on end.’

When the whalemen pulled Traveller out, however, he sprinted back to his clothes, rheumatism free! The treatment did have some side effects – his right hand and part of his right side turned black and he couldn’t keep strong liquor down. A few days later, when he went for a walk round the town of Eden, ‘everyone I met shied at me – a leper could not have been avoided more discreetly. Girls that I knew cut me dead; men whom I considered true brothers held their noses and bolted.’ He didn’t realise why until he met up with Johnson and it dawned on them both how badly they still reeked.

Was it all worth it? Perhaps not. Traveller’s account ends on a forlorn note:

‘For exactly twelve months the rheumatism left me; then it came back again as bad as ever. The smell has never left me: that dead whale haunts me still.’

Vote for Best Medicine!

Best Medicine, which I took part in last November, has been shortlisted for Best Radio Panel Show in the British Comedy Awards! The winner is decided by the public so I’d be very grateful if you could cast your vote for it.

There are other categories where you can choose your favourite TV and radio comedies of the past year - but you can skip any that aren’t relevant to you. Be quick as voting closes on Sunday 21 January at 23:59 GMT.

Thank you - a win would be a real boost for this funny and uplifting series! If you haven’t had a chance to listen yet, you can find all the episodes on iPlayer.

The Goulburn Herald, 11 September 1907.

Louis Becke, A Memory of the Southern Seas, 1904.

The Pall Mall Gazette, 19 February 1896.

The Yorkshire Evening Post, 20 February 1896.

R H Mathews, LS., Ethnological Notes on the Aboriginal Tribes of New South Wales and Victoria, 1904.

‘Traveller’, ‘The Whale Cure for Rheumatism’, The Bulletin, 15 August 1896.