'I am the dead body'

A former medical student made an audacious attempt to get his own death certificate in 1901.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Dr Gideon Marsh was sorry but not surprised to hear about the death of his patient, William Browning. Browning, 35, had suffered from acute kidney disease and, the last time the doctor saw him, was dangerously ill. He appeared to know that his time drew near, as he sent for his brother to come to London.

When Browning first consulted Dr Marsh in January 1901, seeking advice about pains in his back, the doctor prescribed some medicine for catarrh of the kidneys. His condition deteriorated rapidly, however, and a fortnight later he asked Dr Marsh to visit him at his lodgings in Vauxhall Bridge Road. By this time, he could not get out of bed; he had severe pains, swollen feet, a temperature of 103°F, and tests showed high levels of albumin in his urine. Dr Marsh diagnosed Bright’s disease – a now obsolete term that encompassed several kidney disorders.

A remarkable resemblance

It was not, therefore, unexpected that Browning’s brother – who had arrived just in time from the country – should call upon Dr Marsh to inform him that the patient had died at four o’clock that morning. Although this gentleman was a stranger, the family resemblance struck Dr Marsh, who supplied him with the death certificate he requested.

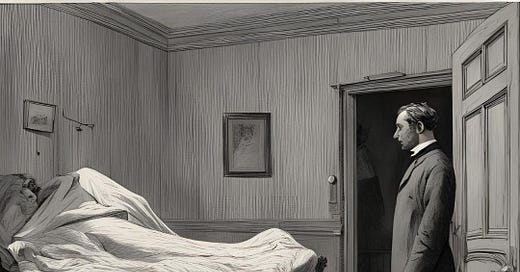

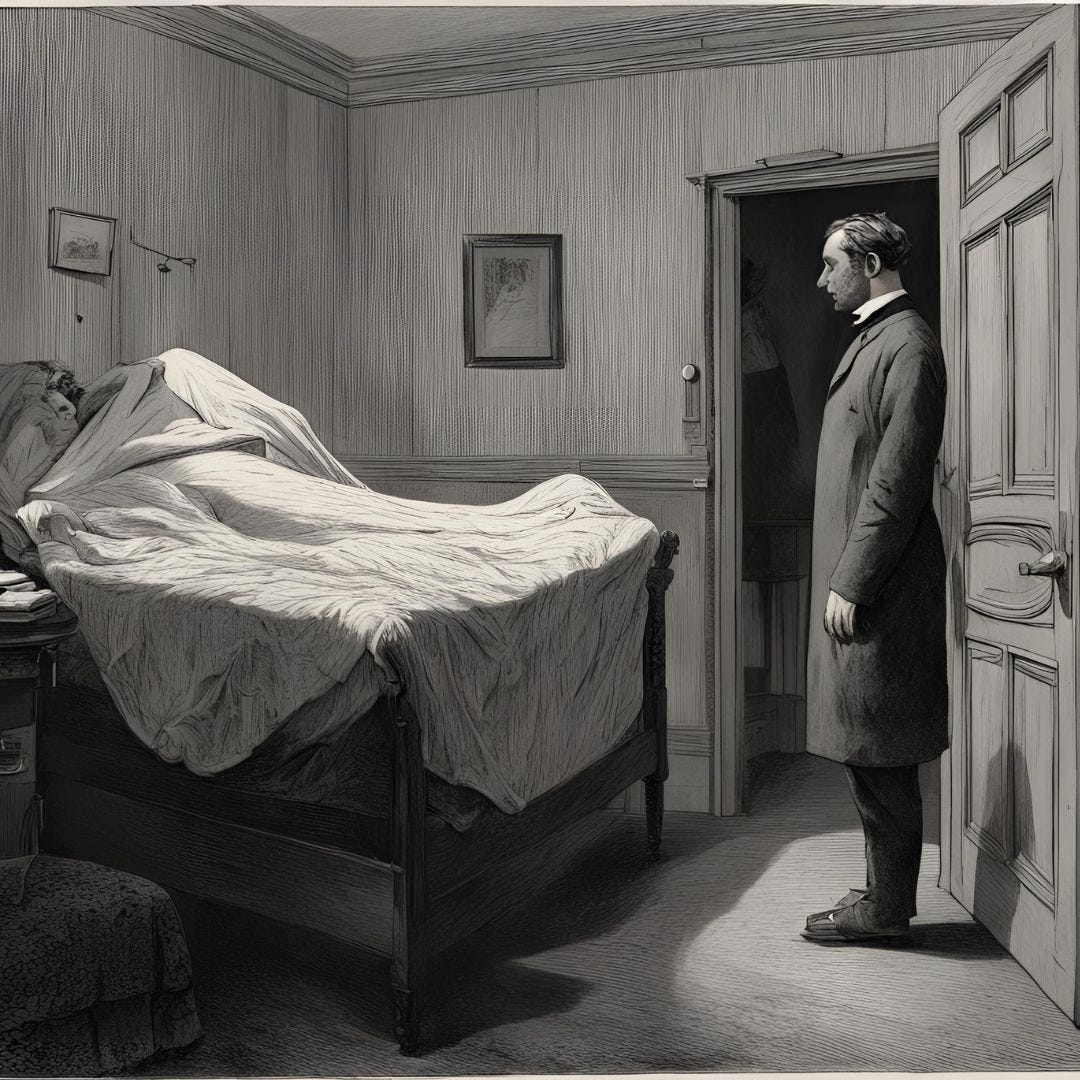

The law did not oblige the doctor to examine the body, but Marsh was a conscientious fellow and always made it his practice to view any deceased people whose certificate he had written. He went to Browning’s lodgings and tried to gain admittance – but an unsettling scene awaited.

The sealed doors of the room were locked. We forced one door, and found the room in darkness. On the bed was the exact outline of a human body. Withdrawing the coverlet, I found it was a dummy corpse—a pillow to form the head, a pair of blankets to form the legs, a pair of boots and a poker.

Dr Marsh informed the police, and Browning – who had shaved off his moustache and put on a different voice in order to pose as his own brother – was taken into custody. In his room, the police found a life insurance policy in his name for £200.

Browning admitted that he had got the death certificate under false pretences. His motive, however, was not an insurance payout – he just wanted to make a fresh start. He reportedly asked the detective sergeant who arrested him:

Can I speak to you privately? I have just been liberated after six months imprisonment, for obtaining money on some shares. I am the dead body. I have done this to make my people believe I was dead.

A photographic poison

During the 1880s, Browning had been a student at the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland, where he presumably gained the knowledge that enabled him to replicate the symptoms of Bright’s disease – right down to the detail of acquiring some urine with high levels of albumin. It is not clear whether he passed any exams but he does seem to have described himself as a surgeon when he moved back to England in 1896 with his new bride Violet.

The couple settled in Nutley, East Sussex, but just five months after their wedding, tragedy struck. Violet reached for a bottle of medicine from a sideboard in the dark and accidentally took some pyrogallic acid that her husband used for his amateur photography. She died in September 1896 and the inquest gave a ruling of ‘death by misadventure’.

The dead body sentenced

In 1900, Browning went to prison for six months for stealing a share certificate for the Broken Hill Proprietary Company from a hotel room, and posing as the shareholder to sell the stock for £256 4s. It was this sentence that he had just completed when he tried the ‘dummy corpse’ trick.

Browning claimed that he had no idea it was illegal to fake one’s own death, but at Clerkenwell Sessions in 1901, this un-dead person – wearing a satin-lined opera cloak over a neat suit – was found guilty of obtaining a certificate of death by false pretences with intent to defraud, and sent to Wormwood Scrubs for nine months (though he was released after six).

His real death many years later had an element of mystery to it too – he was taken ill with pneumonia ‘possibly accelerated by morphia’ at a hotel in Woburn Square, London, and died in hospital in January 1931 without anyone knowing who he was. Scotland Yard confirmed his identity from his fingerprints, which matched those taken at the time of the death certificate fraud. This time, however, he was genuinely deceased.