Josephine Girardelli, the incombustible lady

'The celebrated fire-proof female' entertained Regency audiences with feats of heat resistance

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from the history of medicine and related themes.

It’s free to subscribe, but if you would like to make a one-off contribution to the coffee supplies that keep me going, please go to my Ko-fi page here. Thank you!

Spectators gasped as Signora Josephine Girardelli held red-hot iron in her bare hands, dripped molten lead into her mouth and plunged her toes into a cluster of candle flames.

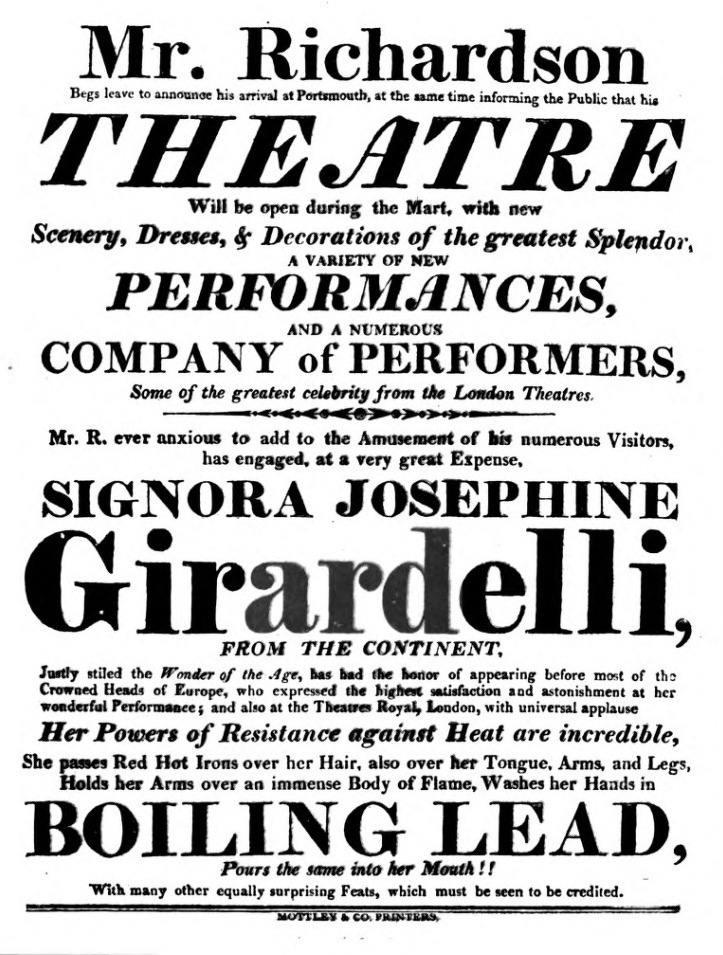

The latest wonder to enthral Regency London called herself the ‘Great Phenomenon of Nature’, and began exhibiting in 1814 at Mr Laxton’s Rooms, 23 New Bond Street. Prior to her arrival, she claimed, she had performed before ‘most of the Crowned Heads of Europe.’ 1

Girardelli belonged to what commentators nicknamed the ‘salamander tribe’, who carried out feats of heat resistance to shock and entertain paying audiences. The science-adjacent nature of their shows reflected a growing interest in pushing the boundaries of knowledge and discovering the extreme capabilities of the human body.

Signora Girardelli’s origins are not clear – while her name suggests she was Italian, and some sources say she was born in Venice, another account claims she was from Munich, and spoke German to her husband. Still another calls her ‘The Incombustible Spaniard’, although this seems to have been a more general term for performers of this type, after one Señor Lionetto or Lionetti went by this description in Paris in 1803. It is also possible that she was a British Jo Bloggs adopting an interesting stage name, although this is just speculation on my part.

But let’s take a look at what she actually did. An article in the Edinburgh Magazine in 1818 gives a detailed account of the writer’s visit to her show.

Before Girardelli appeared, spectators were permitted to examine the props laid out on a table – sealing wax, pieces of lead, a phial of aqua fortis (nitric acid) and more. Then the lady herself stepped out onto an elevated stage behind the table, and assistants brought in a blazing charcoal brazier.

Girardelli’s husband heated a shovel in the brazier and pressed it against a wooden board, which it set ablaze in proof of its genuine heat. She then drew the edge of the shovel along the upper part of her foot and ankle without damage to her skin. Her next trick was to stamp on a piece of hot iron while flames raged round it. She brushed another hot shovel over her hair and along her arms, finally licking it and making it sizzle:

‘In this experiment we were desired to attend to the hissing noise which would be produced, and it was very distinct. She then shewed that her tongue was not injured by it.’2

Girardelli then heated some olive oil, showing how hot it was by breaking an egg into it. She swilled this hot oil round her mouth and then did the same with the nitric acid – which would normally cause severe corrosive burns. Although this performance was nerve-racking for the audience, Girardelli’s serene manner inspired confidence that it would not go wrong. The fact that – unlike most fire-proof performers – she was female and attractive provided an extra element of excitement for some audience members, as a correspondent to The Examiner revealed in 1814:

‘I must say, that I enjoyed to its utmost all the gratification that it is possible for man to derive at seeing one of this delightful sex with a mouth of such capabilities.’ 3

When the Edinburgh Magazine’s writer spoke to her after her show, Girardelli revealed that she did not claim to be naturally any more fire-proof than anyone else; the illusion involved a secret chemical composition applied to her skin in advance. She had found the recipe in books belonging to her father, a chemistry professor called Odhelius at Munich.

A pamphlet published the same year claimed that – for a handsome subscription – she would sit in a beehive-shaped oven alongside some meat or pies while assistants stoked the fires around it. After some time (which must have been a bit tedious for spectators) she would emerge with the now-cooked food and partake of it in front of the audience. This account also says she had unusual strength and could ‘lift with her teeth an anvil of three or four hundredweight, having a child on it.’4

Observers attempted to work out how Signora Girardelli and others of her ilk performed their feats – it was clearly an illusion like those of any conjuror, but no one definitively sussed how she did it.

In Kirby's wonderful and eccentric museum, or, Magazine of remarkable characters (1820), the author implied that only the uneducated would believe Girardelli was truly fire-proof.

‘…that the whole is a trick cannot be doubted; but the vulgar gape and stare, and are fully prepossessed that the fair heroine is by nature gifted with this extraordinary repellant.’5

Possible explanations included sleight of hand – for example, substituting quicksilver for the molten lead and a neutral liquid for the nitric acid. Boiling oil could be simulated by putting water underneath a layer of oil – when heated, air would escape from the water and bubble up, making the oil appear hotter than it really was. Girardelli probably also ramped up the drama of the performance with big flames and lots of suspense, while minimising the length of time she was in contact with the hot iron. Some of her experiments might also have taken advantage of the Leidenfrost Effect, where an insulating layer of vapour forms between a liquid (such as water on the skin) and a very hot surface.

Girardelli’s act toured the UK and Ireland in the 1820s. This time, the fire-proof lady advertised as Madame Girardelli instead of Signora, and appeared alongside her husband, Monsieur Simo Girardelli, whose magical illusions included the Enchanted Snuff Box, the Apples of Beelzebub, the Speaking Money and – most intriguingly of all – the Trick Loaf.6 The couple didn’t always command the audiences such wonders deserved, and in 1829 we find Monsieur Girardelli in Sheffield, advertising tickets at 75% off the usual price. As well as the shows, they exhibited waxworks, including likenesses of the Duke of Wellington, Napoleon and the recently executed murderers Burke and Hare. These were created by Madame Girardelli herself, who seems to have focused mainly on this art rather than fire-resisting at this point in her career.

After 1830, the Girardellis’ newspaper advertisements disappear. Had they returned to the continent to entertain the crowned heads once more? Unfortunately, there was no such triumph – burial records show Josephina Girardelli, wife of Simo Girardelli, dying at Wakefield on 6 July 1830 at the age of 44.7