Medicinal mummy: curse or cure?

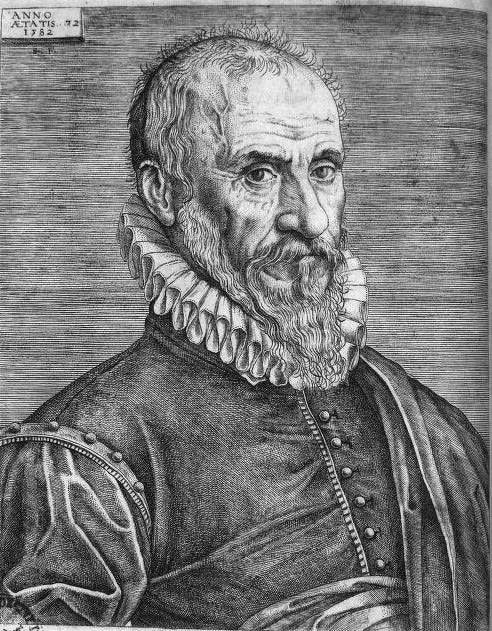

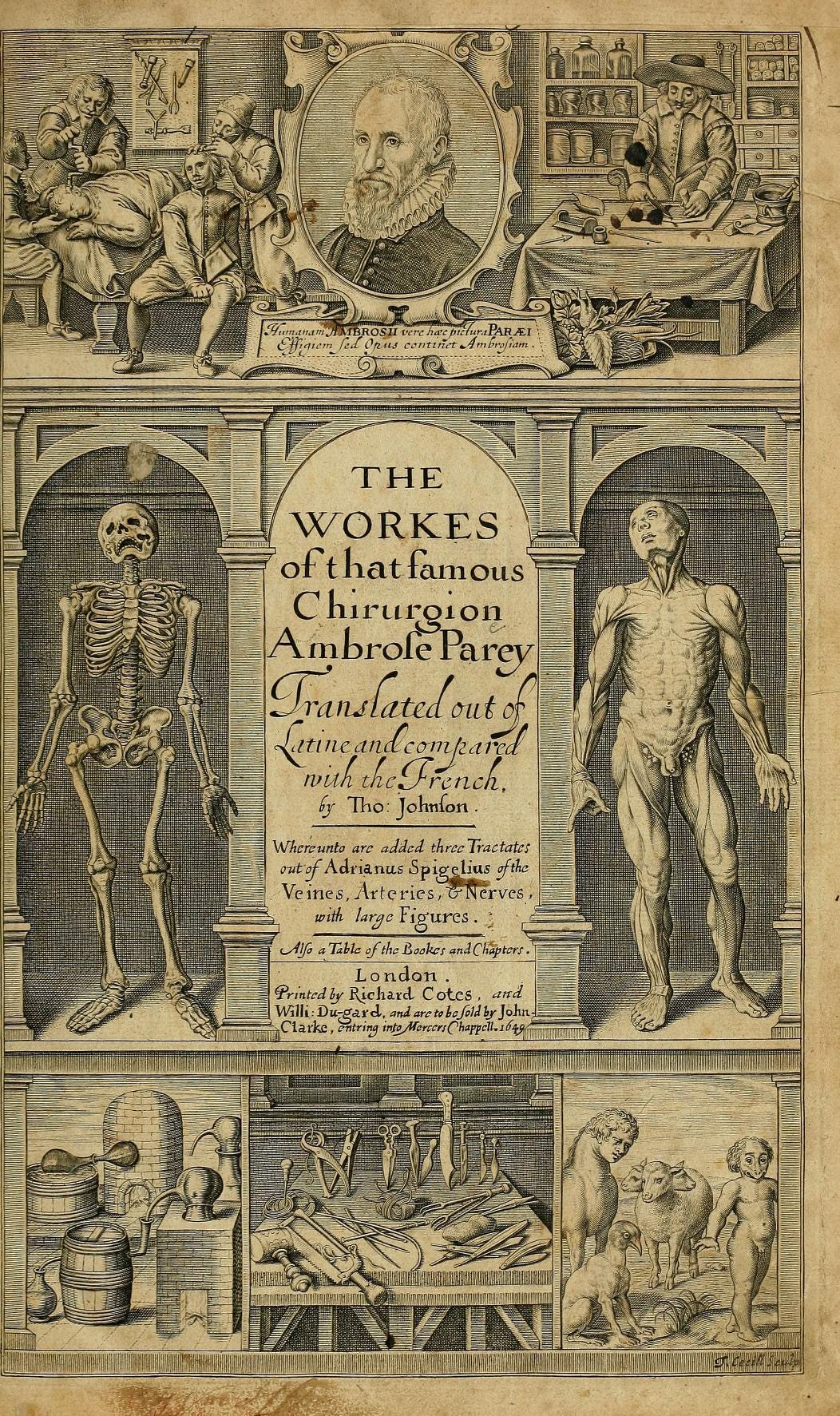

16th-century French surgeon Ambroise Paré disapproved of the fashion for using Egyptian mummies as medicine.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

On a journey from Chaalis Abbey to Armenonville in August 1580, the Chevalier Christofle des Ursins’ horse went over backwards and deposited the Chevalier on a sharp stone, which stabbed him in the kidney area. Almost fainting with the pain, he got scraped up by his friends and taken home.

During his recovery, the Chevalier was attended by royal surgeon Ambroise Paré, and among the topics they chatted about was the use of fashionable remedies. The Chevalier wondered why Paré didn’t give him a substance renowned for its efficacy against bruising and swelling – powdered Egyptian mummy.

The drug ‘mumia’ had gained an excellent reputation in sixteenth-century Europe for its powers against a wide spectrum of ailments, and no self-respecting apothecary would be without a supply. Ambroise Paré (c. 1510-90), however, found the popularity of mumia exasperating and repulsive. His Discours de la Momie (1582) – written as a result of his conversations with the Chevalier – provides an enjoyably forthright debunking of this grisly remedy.

Mumia came to prominence in Europe as a result of some imaginative translations of medieval Arabic medical texts. Ancient Roman and Greek physicians considered the slightly rude-sounding pissasphalt – a semi-liquid bitumen with properties of petroleum and asphalt – to be of medicinal importance. It occurred naturally in the Dead Sea region and at Apollonia in Illyria (in present-day Albania), but a particularly prized source was a mountain in Darabgerd, Persia, where the local word 'mumiya' referred to its waxy texture. The medieval Middle Eastern physicians al-Razi, Ibn Sina and Ibn Serapion the Younger all mentioned a bituminous 'mumia', and it was from European interpretations of their writings that corpses began to get involved.

Gerard de Sabloneta, who translated al-Razi into Latin in the thirteenth century, described mumia as 'the substance found in the land where bodies are buried with aloes by which the liquid of the dead, mixed with the aloes, is transformed and it is similar to marine pitch.'

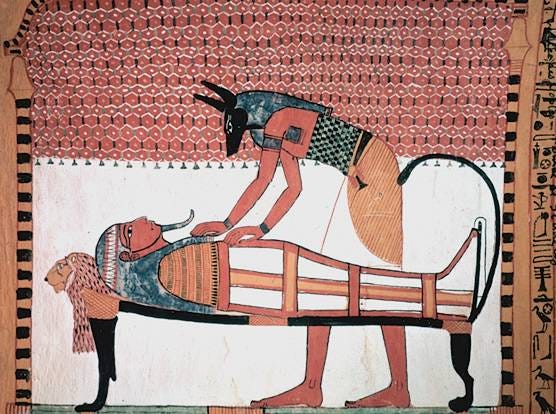

The Liquid of the Dead not only sounds like a great band name, but it also inspired a shift towards a new concept of mumia – an aromatic substance that exuded from the corpses of ancient Egyptians and resembled the pissasphalt of the mountains. Indeed, there was a common belief that the Egyptians had used bitumen in the embalming process and that the bodies were therefore an alternative source. Those local to the sepulchres quickly saw a business opportunity. Before long, not just the exudate but the broken or powdered flesh itself was being sold as mumia. By the early sixteenth century, mumia was also derived from recently deceased persons who had got lost in desert storms and been preserved by the dry heat.

Ambroise Paré is now best known for his innovations in battlefield surgery and his clear-sighted commitment to observation and experimentation. During the Siege of Turin in 1536, his use of a dressing comprising oil of roses, egg yolk and turpentine on gunshot wounds gave soldiers a greater chance of survival than the standard but agonising procedure of cauterisation with boiling oil. He was a prolific writer who aimed to make surgical knowledge more accessible by writing in the French vernacular rather than the Latin of the universities. I imagine him as quite an outspoken person who took no nonsense from anyone, while also treating patients from all walks of life with compassion and respect.

Paré highlighted a few problems with medicinal mummy. First, people didn’t agree on what it actually was. Should one follow Ibn Sina and Serapion’s view that it was pissasphalt, or the contemporary writers Pietro Mattioli and Andre Thevet’s assertions that it was a liquor flowing from embalmed bodies?

Aske the Merchants who bring it to us, aske the Apothecaries who buy it of them, to sell it to us, and you shall heare them speake diversly heereof, that in such variety of opinions, there is nothing certaine and manifest.1

While the surgeon couldn’t be certain what mumia was, neither could he be certain who it was. Paré pointed out that deceased Egyptian nobles, embalmed with myrrh, saffron and aloes, were protected by their descendants, who ‘would never suffer the bodies of their friends, and kindred to be transported hither for filthy gaine.’ The corpses brought to Europe were therefore ‘the bodies of the common sort.’

Paré received information from the king of Navarre’s physician, Guy de la Fontaine, who had visited Alexandria in 1564. De la Fontaine spoke to the merchants selling mummies and discovered that they were not ancient Egyptians but recently executed criminals and ‘other persons indiscriminately collected.’ The merchants prepared the mummies by putting cheap asphalt into the heads, body cavities, and incisions in the muscles. They would then wrap the body and leave it out in the sun until it dried.

One merchant freely told De la Fontaine that he:

…cared not whence they came, whether they were old or young, male or female, or of what disease they had died, so long as he could obtain them, for that when embalmed no one could tell.2

Paré’s Discours suggests that French apothecaries had also begun to cut out the middle man by making their own ‘Egyptian mummies’ – they would ‘steale by night the bodyes of such as were hanged, and embalming them with salt and Drugges they dryed them in an Oven, so to sell them thus adulterated in steed of true Mummie.’

Far from getting the noble exudate of a pharaoh, therefore, you were ‘compelled both foolishly and cruelly to devoure the mangied and putride particles of the carcasses of the basest people of Egypt, or of such as are hanged.’

Paré acknowledged that although the practice was horrible, there might be some mitigation for it if it ended pain and illness. His main objection to mumia, however, was that it simply didn’t work. He had tested this through experience, having used mumia on his patients more than a hundred times before concluding that it was no good. He found that it ‘doth nothing helpe the disease.’ If it had any effect at all, it was to cause abdominal pain, vomiting and stinking breath – perhaps this made some patients and doctors believe that it could purge the body of the poisons of disease.

Paré wasn’t a lone voice in his scepticism, but he did have more influence than most, and by encouraging other practitioners to abandon mumia, he contributed to the remedy’s decline over the next century – although it was still available to some extent into the 1900s. Fascination with Egyptian mummies, however, keeps coming back in new forms – whether in the mummy-unwrapping parties of Victorian Britain or the bandaged monsters of 20th-century film, the mystique of these ancient figures never dies.