Plague, peril and reform: John Howard's quarantine journey

Eighteenth-century prison reformer John Howard set out to experience the grim reality of Venice’s quarantine laws.

With thanks to Paul Yudin on Pixabay for the new voiceover music.

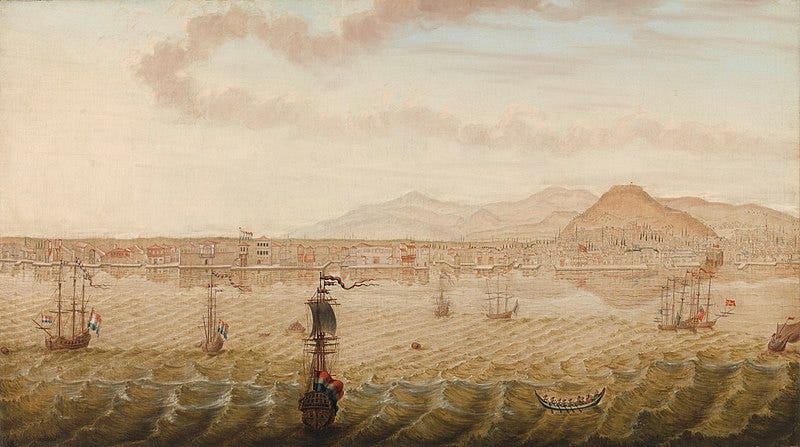

A ship setting off from Smyrna to Venice in 1786 sailed at the mercy of storms and calms, pirates and pestilence. Those on board did not know whether one of their number harboured an infection that could sweep through passengers and crew and leave a ghostly vessel drifting among the Greek islands. Plague was endemic in the region they had left, which labelled the ship with a ‘foul bill of health’. If they made it to Venice, the travellers would face 40 days of effective imprisonment in quarantine.

For most of the ship’s passengers, these risks were unavoidable. They had to get home from their travels, or were heading to Venice for trade. One man on board, however, was there voluntarily. He had gone to Smyrna with the express purpose of embarking on a ‘foul’ ship and finding out for himself what quarantine was really like.

Scenes of calamity

John Howard (1726-1790) had for many years made it his mission to report on conditions in prisons, and to advocate for reform to improve the lives of those incarcerated. When appointed High Sheriff of Bedfordshire in 1773, he had discovered that Bedford Gaol was a squalid hellhole where even those acquitted of crimes languished because they could not afford the 15s. 4d. fee demanded by the gaoler to release them.

Howard began to investigate prisons further afield and tirelessly travelled hundreds of miles on horseback around Great Britain and Ireland, finding ‘scenes of calamity, which I grew daily more and more anxious to alleviate.’ He expanded his research to continental Europe and, in 1777, published The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, with Preliminary Observations and an Account of some Foreign Prisons, which highlighted the inhumanity of filthy conditions, infectious disease and inadequate food.

A foul bill of health

In the 1780s, Howard brought within his investigative remit other institutions with less than desirable conditions – hospitals and quarantine facilities.

The latter – called lazarettos – were used at ports to isolate passengers from regions of endemic plague. Howard visited several Mediterranean lazarettos but, for obvious reasons, it was difficult to gain full access. He therefore travelled to Smyrna (present-day İzmir in Türkiye) and joined the ship that would give him the full quarantine experience first hand. The British consul issued a ship with a ‘foul bill of health’ if even a single case of plague occurred in the region, and it had to perform quarantine at Venice, Leghorn, or Malta. Some merchants believed that Greece originated false plague reports in order to suppress British trade.

It took Howard’s ship 60 days to get from Smyrna to Venice – partly due to unfavourable weather conditions but also because the captain made frequent stops at ports and islands to sell coffee and other goods to the inhabitants. Howard found it frustrating when ‘the opportunity of a fine wind was lost, to gratify the avarice of the captain.’ During these stops, the crew mingled freely with the population on shore – if plague had been present, they would have been passing it around with gay abandon. Indeed, Howard had recently been informed that an entire hamlet in Ragusa (a maritime republic in what is now Croatia) had been wiped out by plague imported in this way. To prevent further spread of the disease, the local magistrate had ordered the two or three survivors to be shot.

A perilous footnote

Plague was not the only danger on the journey. At one point the ship was accosted by a Tunisian privateer, and the crew defended it by firing spike nails from a cannon. The privateer’s retreat saved the passengers from one of several terrible fates; as Howard later found out, the captain intended to blow up his own vessel rather than be murdered or taken into slavery in Tunis. Howard relates this action-packed episode as a footnote; evidently it did not detract from his focus on investigating the lazarettos.

Eventually, they arrived in Venice and Howard describes how he and his baggage were transported in a gondola towed by another boat, a ten-foot-long cord separating him from the rowers. At the Lazzaretto Nuovo, he was shown to ‘a very dirty room, full of vermin, without table, chair or bed.’ He developed a constant headache, and after the British consul intervened, he was transferred on health grounds to the Lazzaretto Vecchio nearer the city.

Saturated with infection

Howard hoped that his letter of introduction from the Venetian ambassador at Constantinople would help him wangle better accommodation, but his hopes were in vain. The rooms assigned to him were just as bad as those in the Lazzaretto Nuovo, and Howard ended up lying on a brick floor ‘almost surrounded by water.’ After six days he was moved to a larger apartment, which proved equally dirty and smelly but at least had a pleasant view. The walls, ‘not having been cleaned probably for half a century, were saturated with infection.’ He had them repeatedly washed with boiling water, but this had no effect and he lost his appetite, fearing that he would contract a fever. His idea of getting the walls whitewashed met with opposition from his guardians. Through the influence of the British consul, however, he got the job done and was almost immediately able to have a cup of tea in the newly tolerable environment.

There was not much to do in quarantine, and Howard used the time to study the regulations of the Venice lazarettos and formulate recommendations for a similar – but more salubrious – institution off England’s coast. He published his conclusions in An Account of the Principal Lazarettos in Europe in 1789, arguing that an English lazaretto would not only prevent plague arriving with goods via European countries that were less diligent about quarantine, but would also boost the economy by enabling more efficient trade with the East. The plan did not ultimately come to fruition but highlighted the inadequacy of quarantine measures. Included in his account was correspondence from physicians in the Mediterranean ports giving their opinions on the transmission, symptoms and treatment of plague – an interesting insight to which I might well return in a future article.

Howard’s legacy

In the face of personal danger, John Howard persevered in his mission to understand and improve quarantine conditions. His experience in the lazarettos of Venice revealed the grim reality of isolation, where cleanliness was a luxury and disease lurked in every corner. His commitment to collecting information about prisons, hospitals and lazarettos, as well as contemporaries’ descriptions of him as eccentric, have led to the suggestion that he was on the autism spectrum – something that it is not really possible to know, but which is an interesting theory to consider.

Today, Howard’s legacy continues to inspire efforts towards compassionate and effective responses to social issues, echoing through the work of organisations like The Howard League for Penal Reform, which uphold his vision of a more humane society.

Haunted History Chronicles

On the 12 April episode of the Haunted History Chronicles podcast, I chat to host Michelle Fisher about Charms and Charlatans: The Intersection of Quackery and Mysticism. We look at some cases where medical fraudsters have used tales of the supernatural to influence their victims. Click here to listen.