Plague in Suffolk, 1910

Centuries after the Great Plague decimated London, an isolated outbreak struck two unfortunate families in the East of England.

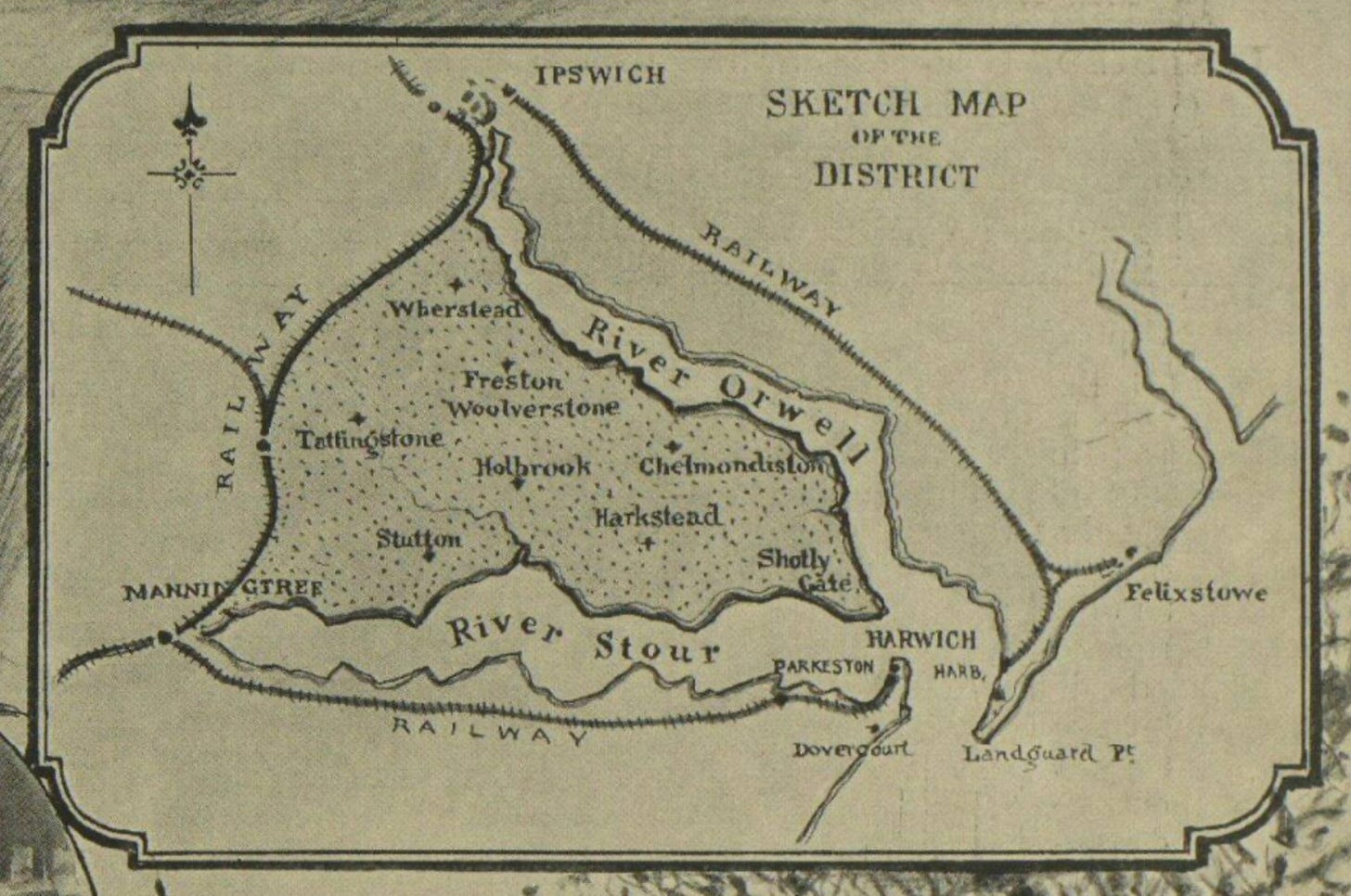

A great many rats died on the Shotley Peninsula as the autumn of 1910 approached. It was the time of year when farmers laid down rat poison, and the district Medical Officer of Health thought this must be the cause – at first. Hares and rabbits sometimes died inexplicably too, and the occasional ferret or cat.

When violent symptoms struck humans, however, the authorities discovered what they were dealing with. Plague, the most feared disease in human history, had invaded 20th-century Suffolk.

Plague was no distant memory – the Third Pandemic had killed millions in India and China since 1855, and in 1900 an outbreak in Glasgow was contained by a swift official response of contact tracing, quarantine and sanitary measures.

On 13 September 1910, nine-year-old Annie Goodall of Freston started vomiting at school. The next day, Dr William Carey visited and found her with a temperature of 105°F. By 15 September she was delirious and breathing rapidly, with crackling sounds detectable in her lungs. Overnight, she began coughing up blood, and died early in the morning of the 16th.

Annie and her family lived in Latimer Cottages on the Holbrook Road, having moved there from nearby Ipswich just a few months before. Her stepfather, George Chapman, worked as a farm labourer and her mother Frances looked after the home and the four youngest children from a previous marriage. The day after burying her little girl, Frances Chapman became unwell with a headache and high temperature. She managed to go and see Dr Carey to ask for some medicine, but when he subsequently visited her at home, she was much worse. Her condition deteriorated rapidly and a neighbour, Agnes Parker, came to look after her.

The disease identified

Dr Carey knew this wasn’t some ordinary malady. His patient was ‘almost pulseless, respiration laboured and gasping’1 after a night of diarrhoea and vomiting. He asked Dr Herbert Brown of Ipswich to consult on this unusual case, but by the time Dr Brown arrived, Frances was dead. Dr Brown obtained some of her sputum – which he graphically described as ‘brownish in colour, as though tinged with anchovy sauce’2 – and sent it to the Ipswich Hospital bacteriologist. It contained large numbers of pneumococci and gram-negative bacilli, but the analyst was unable to prepare a culture to identify them conclusively.

On the morning of Mrs Chapman’s funeral, her husband went to work on the farm as usual, but had an aching back and said he was ‘feeling bad’. He attended the service but then had to go home to bed. At the same time, Agnes Parker developed severe symptoms of pneumonia. Samples of blood and lung fluid from these patients showed the presence of the plague bacterium Pasteurella pestis (now Yersinia pestis). These cases took the pneumonic form, which is rarer than bubonic plague and can be transmitted from person to person. The doctors knew that ‘energetic measures’ were immediately necessary to stop it from spreading.

The first step was to isolate the two patients in their homes. Hospital nurses came from Ipswich to care for them, but their families were not allowed to enter the house. The three remaining Goodall children, having just lost their mother, had to sleep in outbuildings and were later taken to the workhouse hospital at Tattingstone along with Mrs Parker’s family. On 29 September, both George and Agnes died. Their funerals were conducted entirely in the open air and those attending had to disinfect their clothes. Those who had been in contact with the patients were quarantined for ten days and the two houses were cleared out so that all possessions could be either disinfected or burned, and the walls repapered.

A war on rats

As ever, the humble rat was incriminated. Tests on animals found dead or trapped showed that they did indeed carry the bacteria.

The district Medical Officer, Dr H P Sleigh, writing later in the British Medical Journal, noted that the plague had ‘picked out two very dirty households’ and that ‘only those with little respect for hygiene were infected’.3 This sounds insensitive towards the affected families, but it was essential that people were encouraged to improve sanitation and eliminate vermin from their living areas.

The Samford Rural District Council issued a public warning that the rat population carried ‘a very Malignant and Fatal Disease, which may be communicated to human beings.’ They ordered the public not to touch dead animals, to avoid eating rabbits and hares, to burn any accumulations of refuse, to keep food covered and to mount ‘a General Campaign against Uncleanliness and Insects.’ The market for rabbit meat disappeared almost overnight. One game dealer who couldn’t shift his stock ‘declared that he would cook them for his dog’ and ‘admitted that he did not fancy them himself.’4

Ideally, rats would be eradicated. While the District Council was reluctant to supply everyone with rat poison, individual householders, farmers and gamekeepers began an onslaught against the creatures, using traps, poison, ferrets and dogs to deal with as many as possible. Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reported that the Suffolk countryside was dotted with bonfires, ‘the curling wreaths of smoke against the landscape revealing the funeral pyres of hundreds of rats,’5 and that some villagers had even started killing cats too. The Suffolk papers, however, were less dramatic and described people doing their best to sort out the rat problem and protect their families and communities.

The outbreak was contained. Annie’s sisters lived long lives, all surviving into the 1980s. Isolated cases of bubonic and pneumonic plague occurred in Suffolk up to 1918, when Erwarton neighbours, Mrs Bugg and Mrs Garrod, died. Whether the disease ever returns to these shores remains to be seen, but the UK is plague free for now.

From The Quack Doctor archives…

The human X-ray scientists

Imagine being able to see through a steel door, or to force the germination of poppy seeds and at once destroy them with the power of your mind. Such were the abilities claimed by Albert Isaac Grant of Maidstone, Kent, in the years leading up to the First World War.

Grant, a former sanitary inspector and insurance superintendent, began practising as a healer in around May 1910. His powers could not only influence vegetation but also diagnose disease and generate new internal organs. Any malady would bow to his mastery but the people who needed him most were those with consumption, cancer, or blindness.