Rascality in Hot Springs

Quack doctors in a 19th-century spa resort used the devious tactic of 'drumming' to lure in customers

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from the history of medicine and related themes.

It’s free to subscribe, but if you would like to make a one-off contribution to the coffee supplies that keep me going, please go to my Ko-fi page here. Thank you!

A spa should be a place of tranquillity and health-restoring wholesomeness. While present-day spa establishments sometimes teeter on the edges of quackery (or even plunge right in), that’s nothing to the dangerous scams operating in the 19th-century resort town of Hot Springs, Arkansas.

The naturally occurring hot water flowing from the area’s mountain springs attracted visitors keen to relieve rheumatism and other diseases. It reputedly cured scrofula, syphilis, asthma, catarrh, paralysis, menstrual problems, alcohol addiction and more, as well as beautifying the complexion and restoring hair to bald heads.

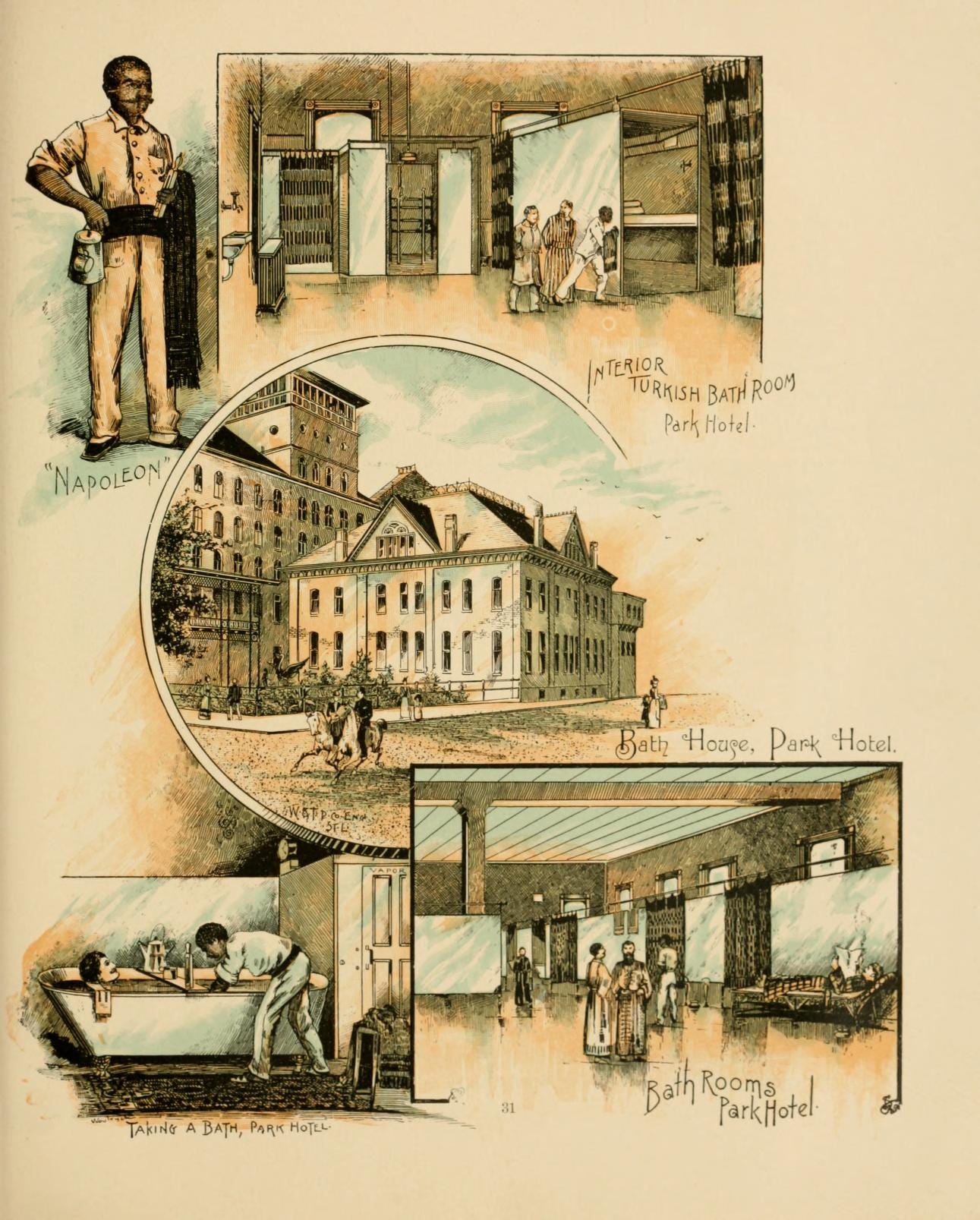

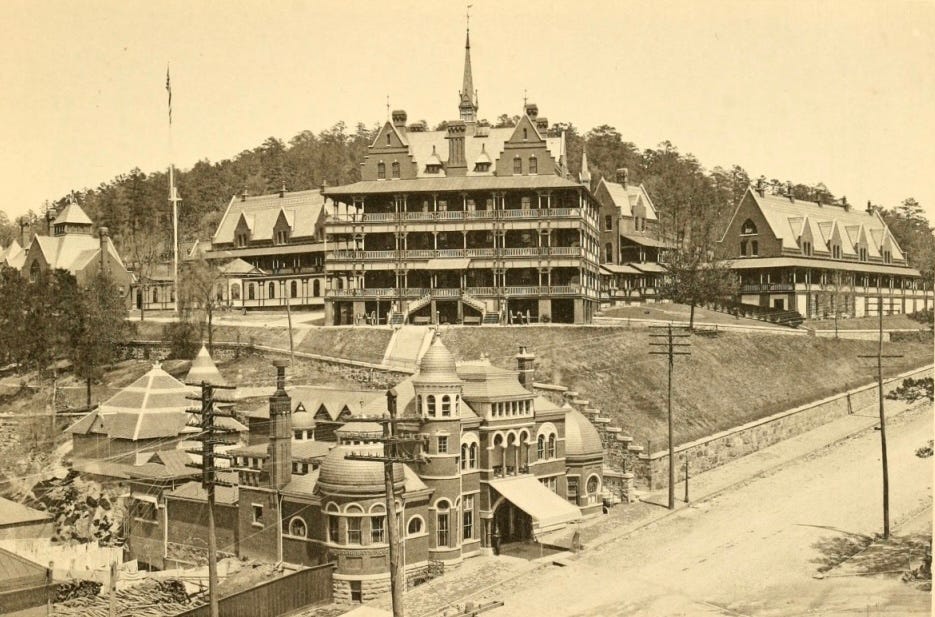

Hot Springs – for thousands of years a gathering place for indigenous people including the Choctaw and Cherokee – became a federal reservation in 1832. Over the rest of the century, hotels and fancy bath houses sprang up to cater for guests’ needs. Physicians gravitated to a place where many wished to obtain medical advice before bathing, and it became customary for a doctor to prescribe the frequency of baths and the amount of time one should spend in the water, depending on the ailment in question.

Some of these doctors were honest and reputable. Others were most definitely not.

During the last few decades of the 19th century, a seedy underbelly emerged to this attractive and fashionable resort. Hot Springs already had problems with illegal gambling, and its reputation was further dented by a plague of ‘drummers’.

This might conjure up images of percussion musicians roaming the streets and disturbing the health-seekers’ peace, but no – this type was much quieter and sneakier.

A drummer set out to ‘drum up’ business by befriending tourists and recommending a specific doctor, hotel or bath house – who would pay a handsome commission. In 1878, an article in Harper’s Magazine warned readers to avoid these dodgy characters:

Physicians of all kinds abound at the Springs, from able practitioners to the veriest quacks. As a safe rule, never employ one whose agent has approached you, or whose circular has been handed you on nearing the springs. There is an immense field for quackery, and it is worked to its fullest extent.1

Drummers frequently operated at Malvern, from which a narrow-gauge railway (opened in 1874 and upgraded to standard gauge in 1889) transported visitors the last 22 miles to Hot Springs. They would also go further afield to Little Rock and St Louis in search of the wealthiest passengers.

Common practice was for the drummer to seat himself next to a rheumatic-looking person on the train – preferably one who appeared well off – and engage them in conversation. If it transpired that the passenger was heading to Hot Springs for health reasons, the drummer would remark on the happy coincidence that he, too, was going there to repeat the wonderful experience of a previous visit. He would be only too glad to introduce his new friend to the best physician in the place!

Part of the drummer’s task was to assess how much money the patient had, and relay this information to the doctor so the consultation fees could be adjusted accordingly. Although the ‘drumming nuisance’ was well-known and warnings abounded to inexperienced travellers, the drummers were experts at gaining people’s trust. According to a newspaper report in 1890, a detective of Chicago’s famous Pinkerton Agency was taken in by a ‘very innocent and unsophisticated youth’ who turned out to be ‘one of the sharpest confidence men and most successful drummers on the road’.2

In 1893, the City Council passed an ordinance requiring drummers to have a licence costing $25 a year, and to wear a badge with the words ‘Drummer for…’ whichever doctor or bath house employed them.3 Unsurprisingly, the drummers simply carried on as normal.

In 1898, the Secretary of the Interior, Cornelius Bliss, sent inspector J W Zevely to report on the situation at Hot Springs. Zevely related a shocking case that showed the extent of the dodgy doctors’ unethical and dangerous tactics.

A drummer brought in a patient and privately told the doctor that this one should be good for a fee of $25. An examination duly took place, and the doctor reassured the man there was nothing seriously wrong with him.

But when it came to paying the bill, the man whipped out a huge wad of cash and peeled off the notes. The drummer had clearly missed a trick in his wealth assessment, and the doctor was not happy. He called him a fool and ordered him to get the patient back in.

The drummer followed the patient and informed him that the doctor was not quite satisfied on one aspect of the consultation. A further examination of the poor fellow’s abdomen purportedly revealed he had a tumour that must be removed without delay.

Frightened out of his mind, the patient consented to surgery, which was carried out immediately. The doctor made a shallow incision in the abdominal skin and then stitched it back up. When the patient woke from the chloroform, he learnt that the operation had been a success, and a tumour in a bottle was exhibited to him as the one that had just been removed. He paid $500 for this bogus procedure.4

Various medical and civic groups made attempts to clamp down on the practice of drumming – whether by licensing, distributing warning leaflets on the trains, or by attempting (but failing) to pass a bill in the state legislature to prevent doctors employing drummers.

One incident in 1896, however, escalated the conflict between drummers and the authorities. The Mayor of Hot Springs – the appropriately named W W Waters – had been tough on drumming, trying to enforce the 1893 ordinance by having unlicensed practitioners arrested and fined. One of these, Harry Martin, stopped Waters in the street and tried to persuade him to remit the fine. He became increasingly angry and abusive when Waters refused, and a scuffle ensued.

Waters drew a knife from his pocket and stabbed Martin repeatedly in the throat, severing a jugular vein. He bled to death in 10 minutes. The Mayor turned himself in to the police and was subsquently tried for manslaughter – but acquitted.5

The ‘drumming evil’ persisted into the first two decades of the 20th century. In 1909, government officers began boarding trains and announcing to passengers that anyone consulting doctors who employed drummers would be denied access to the baths.

It was not until 1916, however, that significant progress occurred. A group of anti-drumming physicians and hotel proprietors employed the William J Burns International Detective Agency to gather evidence.

The detectives planted dictaphones to record incriminating conversations between doctors and drummers, and female sleuths posed as rich patients to observe the attempts to overcharge.

The evidence was presented before a Grand Jury, with the result that fourteen physicians were struck off the register and 17 hotels barred from sending guests to the bath houses.6 Although low-level drumming did continue to some extent, the worst of the scams had come to an end.

I love everything about the history of Hot Springs, from the treatments which basically mimicked those being given at insane asylum to these clever drummers. Thanks for sharing this tory!