Secrets of the mummy factory

A Los Angeles artisan earned a fortune creating fake Egyptian mummies for showmen and museums

Craftsman John E Fisher told the reporters he’d had enough of the business that had sustained him for nearly three decades. Now approaching 50, he had grown uncomfortable with the way some less scrupulous people used his products to mislead the public, and decided on an early retirement. Before shutting up shop, he offered paying guests the chance to observe the intricacies of his craft.

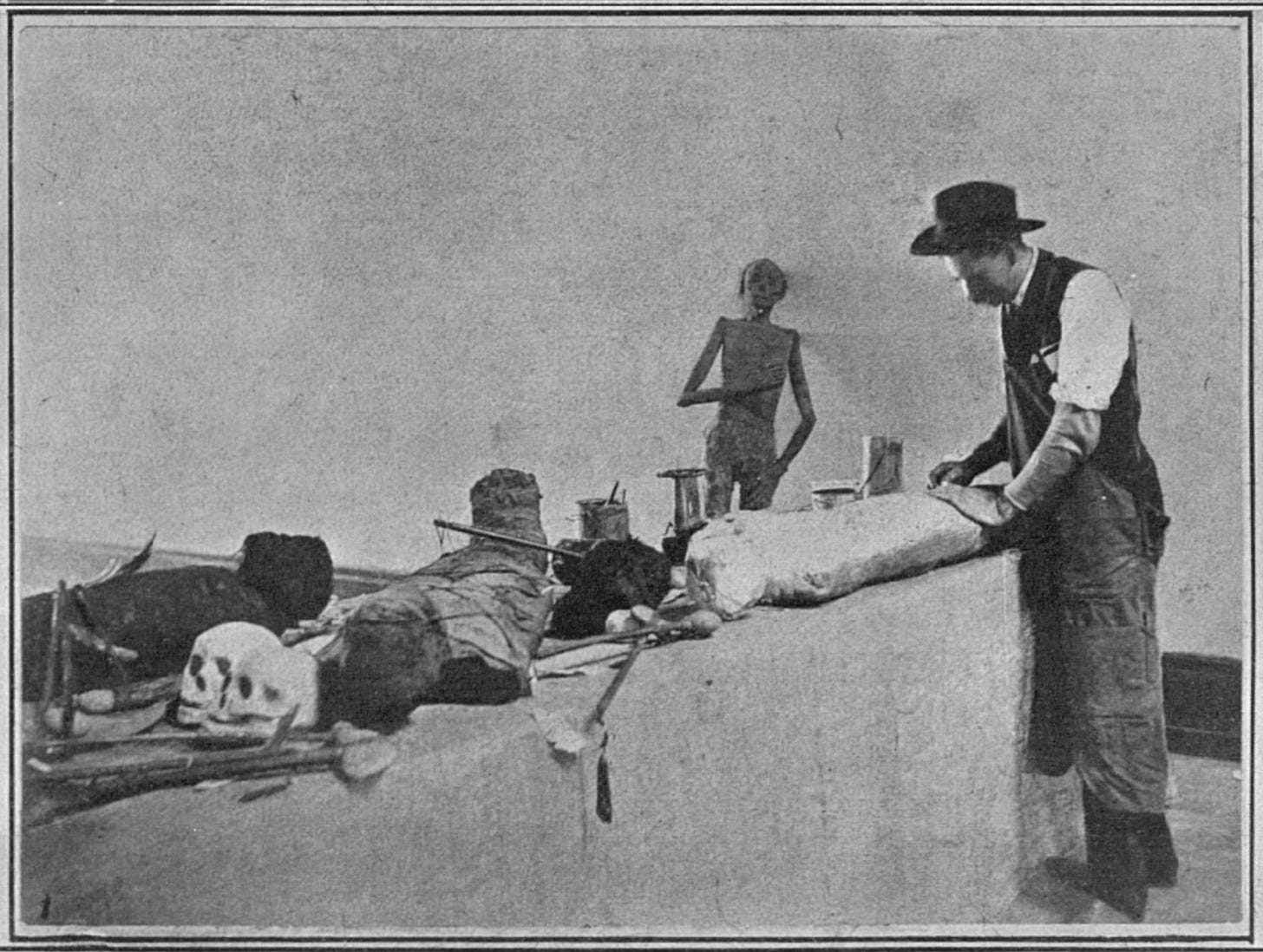

Fisher was an expert mummy maker, building replicas of Egyptian antiquities for museums and exhibitions. From his workshop at 525 South Spring Street, Los Angeles, the counterfeit dead were shipped far and wide – including (allegedly) to Egypt to be ‘discovered’ by explorers. In 1906, he started inviting the press to see him at work. Reporters described him as ‘a clever sculptor’, ‘a cheerful cynic,’ and ‘a pleasant man, this maker of dead people.’

The construction of a mummy began with a plank of wood, which took the role of a vertebral column to keep the thing rigid. Two shorter pieces of wood were nailed to one end to represent the feet. Then a sack was placed around the framework and stuffed with excelsior (wood wool) to create the shape of a human body. Bamboo and small sticks became the ribs, arms and fingers. Fisher covered this with a thin coat of plaster followed by a layer of glue. He pasted on a fluffy tissue substance and again coated it with glue. After this, he attached a plaster of Paris head and coated this in the same way as the body. Real tufts of hair, and teeth made from cow horn, were added and the whole thing partially wrapped with ragged strips of cotton, allowing areas of bone and skin to show through. After being painted and left to dry, the mummy was strewn with grey dust-like powder, giving it the appearance of one who had resided in a tomb for thousands of years. Henry Simon of The Pacific Monthly wrote:

‘The very shape of the head, the expression of the hollow eyes, the shriveled lips, the bits of skin and bone exposed; the general aspect and pose of the limbs and body, wrappings and all, are such as to exactly resemble the genuine article, and would, were the result of the artisan’s labor exhibited in a museum, deceive any but the eye of an expert – and his too, unless he looked very close.’1

That was just the basic model. For customers requiring a top-of-the-range corpse, Fisher used real human skeletons procured from surgical colleges. He aged the bones artificially using chemicals and added desiccated animal entrails. These mummies sold for $1000.

Fisher designed the mummies to appear fragile, so that anyone handling them would treat them with reverence and not chuck them around enough to discover the deception. He reportedly said:

‘Not one in a hundred of the mummies brought from Egypt to America are genuine. I have personally made, or superintended the making of, no less than a thousand Egyptian mummies, many of which have been shipped to Egypt, there buried in secrecy, and the following year dug up by some fake explorer, shipped back to America and exhibited as a newly discovered mummy.’2

According to Fisher, the Egyptian government was in on the joke and tolerated the fake mummy trade in order to satisfy explorer-tourists and keep them away from the genuine deceased.

In May 1906, the San Francisco Chronicle claimed that Fisher had disappeared from South Spring Street after having attracted attention from the press, but this seems a little melodramatic – he remains on voter registration indexes for the city and seems to have simply retired and moved house.

The Chronicle related that Fisher grew up in Germany and followed his father’s trade as a taxidermist. On a year-long visit to Egypt he studied mummies and realised that his taxidermy skills could be adapted to the creation of replicas. He and his brother created one that they sold to Barnum, who was in Europe at the time. After arriving in the US, he made and sold his macabre wares in New York, Montana, Idaho and Ohio, before settling in Los Angeles.

The Chronicle’s writer. T. Shelley Sutton, described the South Spring Street workshop in gothic terms:

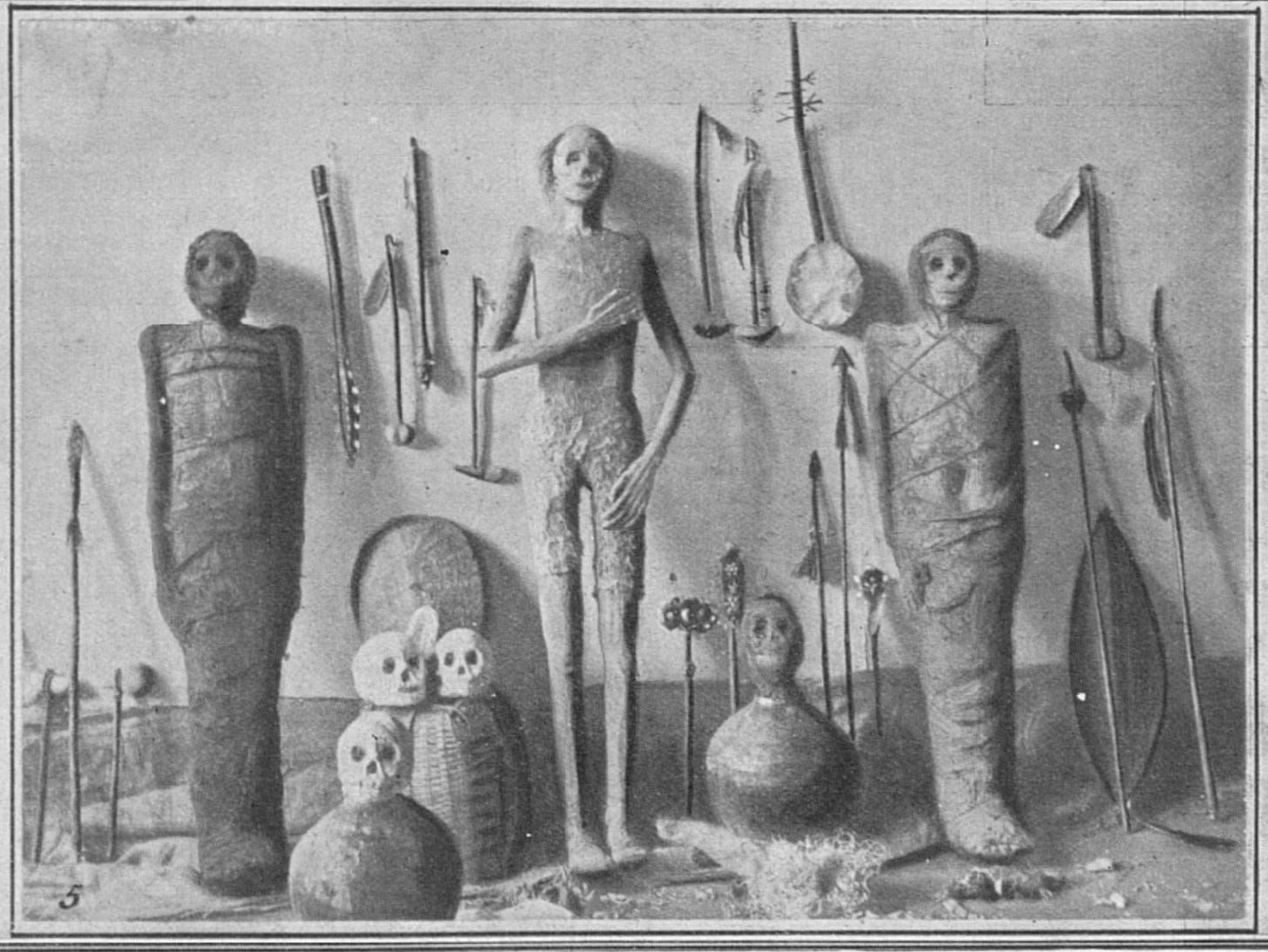

‘Against the walls were dozens of vermiculous and decomposed coffins, and a score of ghastly, grinning “corpses” were leaning around in various positions. Dozens of skulls, bones and torsos, finished and unfinished, lay all about me. Great mats of hair, little piles of teeth and finger nails, and broken ribs and rotted beads, with heaps of yellow winding-cloth, and hundreds of mummified monstrosities, including cats, babies and dogs, made hideous the dingy laboratory.’

Fisher said he placed his business card somewhere in the body of every mummy he made ‘as a sort of sub rosa jest.’ He and his wife had enjoyed a visit to the Smithsonian, where they laughed at the serious descriptions on exhibits he recognised as his own.

Fisher’s talent extended to the creation of other curiosities too. He could make a huge gelatinous octopus that appeared to be alive when suspended in water laced with a soda and saltpetre formula. Everything from Sanskrit parchments to rusted Revolutionary swords, Aztec sacrificial stones to Native American war relics could be created to order.

In the San Francisco Chronicle interview, Fisher described being asked to make a ‘petrified man’, which the purchasers wanted to use for a hoax. He did the job for $500 but, after the body had been buried and dug up, the owner asked him to go and verify that it was genuine. Fisher told him ‘I would not give my aid to fleecing the public,’ and got into a quarrel. Yet he was clearly making a lot of money knowing exactly what his creations were intended for.

The ambiguous boundary between fraud and honesty seems to have increasingly occupied Fisher’s thoughts towards the end of his career. He pointed out to interviewers that ‘I have never yet said that my work was genuine. I have simply sold the stuff to men who did … I make them, I sell them as imitations, and the man to whom I sell them exhibits them as genuine. That is no fault of mine.’

After leaving off his mummy-making business, Fisher moved on to giving talks and demonstrations about his craft. In Pomona in 1911, for example, he appeared as a Valley Fair attraction, showing the audience how mummies were created and warning them to avoid paying big prices to see exhibited fakes. He told the Pomona Daily Review that he was ‘through with even indirectly fooling the public now.’3

It is unlikely that, with today’s methods of scanning and carbon dating, there would be any Fisher mummies left in museums – but who knows? Perhaps one a day a curator will come across a business card pasted to the wooden foot of a fraudulent pharaoh.

HistMed Highlights

SHAME AND MEDICAL HISTORY: Dr Jennifer Evans of the University of Hertfordshire presents this seminar about the extent to which genitourinary disorders caused embarrassment for early modern patients and affected their interactions with medical practitioners. Wellcome Centre for Cultures and Environments of Health, The Queen’s Drive, Exeter, EX4 4QH. 8 February 2024, 2pm GMT. Free admission - reserve a place for in person or online attendance.

POLITICS AND PANDEMICS: In this interdisciplinary workshop, Dr Kavita Sivaramakrishnan from Columbia University discusses the history and politics of pandemics, with a particular focus on immunity and care in colonial and post-colonial India (1900-1960). Colin Matthew Room, Radcliffe Humanities Building, Oxford OX2 6GG. 9 February 2024, 9.30am GMT. Free admission - reserve a place.

DIGITAL EXHIBITION: The National Library of Medicine’s new online exhibition, Making the Greatest Medical Library in America, showcases a selection of 19th century pamphlets acquired early in the NLM’s history and celebrates the continuing work to collect and preserve the world’s medical knowledge.

Henry Simon, ‘The Making of Mummies’, The Pacific Monthly, June 1906.

T. Shelley Sutton, ‘The man who makes mummies 4000 years old,’ The San Francisco Chronicle, 13 May 1906

‘Mummies made to order just like ham and eggs’, The Pomona Daily Review, 13 September 1911.