‘So worthy of the public notice’: the art of Sarah Biffin

19th-century artist Sarah Biffin, who was born without arms or hands, painted exquisite miniature portraits

I first ‘met’ the 19th-century artist Sarah Biffin about 15 years ago. I was attempting to write a second novel, a Victorian pastiche set in the world of freak shows and – of course – quack doctors. My heroine, Tilly, unexpectedly finds herself taking on the care of an abandoned baby – abandoned because she was born without arms or legs. Tilly must try to protect her from a showman eager to profit from her disability.

I made it to a complete draft but had structural issues that felt insurmountable, and struggled with the portrayal of some real-life historical figures whom I had set my heart on including. The announcement of a film about ‘my’ characters disheartened me further and I felt I had missed my chance to tell their story first. The film never happened but I moved on to other things.

Sarah Biffin (1784-1850) was not actually one of these real-life characters, but I researched her experiences because she had the same condition – phocomelia – as baby Ginevra in my book. Last weekend I visited Tate Britain’s Now You See Us exhibition with Nicola Morgan of Story is Probably More Important Than You Think – we’re making an episode about it for our podcast, She Wrote Too. I had somehow managed to miss Philip Mould’s exhibition Without Hands in 2022, so I was particularly looking out for Sarah Biffin’s self-portrait, which presents this accomplished miniaturist as she wanted the world to see her.

Sarah Biffin was born into a modest farming family at East Quantoxhead, Somerset, on 25 October 1784. She was without hands or arms, and had vestigial legs. As a child, she showed natural creativity and came up with a system of using her mouth and right shoulder to accomplish tasks such as sewing, writing and subsequently painting.

At about 19 or 20, she signed a contract with an employer called Emmanuel Dukes and lived with his family for several years. Most accounts present him as a travelling showman but it seems more likely that he was an artist from whom Biffin aimed to receive training. Certainly an 1830 directory of Basingstoke lists a man of that name as a ‘historical, landscape, miniature and portrait painter,’ which seems a remarkable coincidence if it’s not connected.1

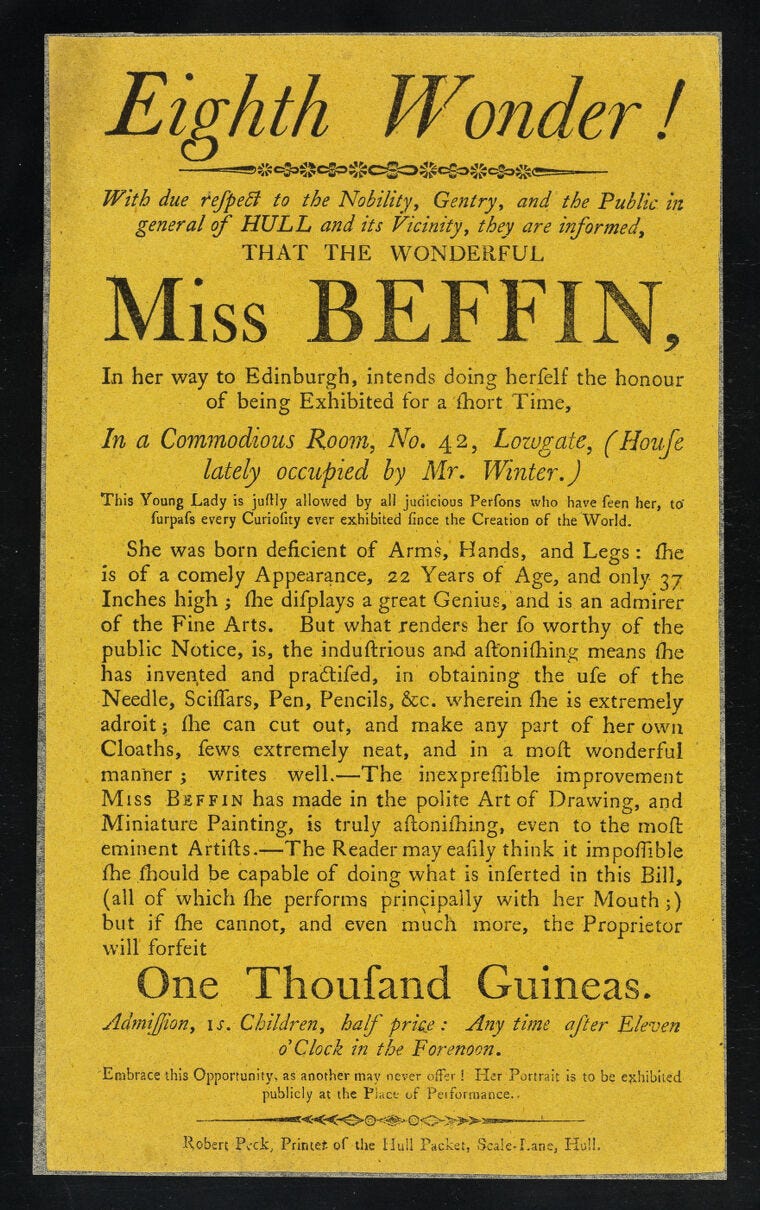

Whoever he was, he did see the opportunity to make money from his pupil in an age when spectators would pay to visit fairground booths exhibiting ‘unusual’ individuals. Biffin’s career at this point is characterised by a complex mixture of exploitation and artistic development. Dukes’ handbills promoted her in traditional freak-show language as ‘The Eighth Wonder!’ and he kept most of the money made from entry fees and the sale of her paintings. Conversely, Biffin lived comfortably as part of Dukes’ family. She gained the chance to travel, to build her artistic reputation and learn promotional techniques. She also encountered opportunities that – alongside her own entrepreneurial spirit and determination – would lead her to an independent career.

George Douglas, the 16th Earl of Morton, met Biffin in 1808 and recognised that this wasn’t somebody daubing a few brushstrokes for the sake of an audience’s low expectations. Her work was exquisite, on a par with Royal Academy exhibits. He arranged for her to receive further training from miniature painter William Marshall Craig, which enabled her to refine her skills. The Earl remained a good friend to Biffin and promoted her work among his social contacts, leading to some high-profile commissions. In 1821, she received the Large Silver Medal from the Society of Arts for a miniature of the Holy Family, and the same year had a painting exhibited at the Royal Academy for the first time.

Biffin worked in watercolour on ivory, or sometimes vellum, using a brush supported by a loop on the clothing of her right shoulder. With the brush thus prevented from falling, she could use her shoulder and mouth to manipulate it with precision. The brush appears in her self-portraits, a subtle but important symbol of her talent. Some insight into her method appears in a Scottish periodical called Hogg’s Weekly Instructor in 1847. The author looks back to having met Miss Biffin many years earlier and recalls seeing her write:

In the first place, she bent her head forward to the table, and, seizing a pen from the inkstand with her tongue and lips, she placed it with amazing quickness and precision between her cheek and her right shoulder stump, and still leaning forward, wrote her name on a piece of paper in a clear and legible female hand. In thus writing, all the necessary motions were made by the head and neck in conjunction with the stump, which she held pressed to her cheek to retain the pen in its place.2

A somewhat mysterious episode in her life is that of her marriage to William Stephen Wright in 1824. She had apparently known him for several years and some accounts suggest that he had been ‘long attached to her’.3 Once they got married, however, Mr Wright quickly proved to be Mr Wrong. They did not live together and he ‘soon ceased to visit her’.4

Within the Victorian social context, marriage was a useful marker of respectability, and Biffin continued her career under the name ‘Mrs Wright’. As well as holding exhibitions in numerous British towns, she offered instruction in miniature painting to aspiring artists, either in person or by correspondence. In 1830, King George IV gave her £25, having been impressed by a miniature sent to him.

Unusually for the time, ‘Mrs Wright’ reverted to her own name of Miss Biffin when she moved to Liverpool in 1841. Although she was ambitious to travel to America, circumstances conspired against it – her eyesight deteriorated, and commissions were drying up. A philanthropist, Richard Rathbone, took an interest in her and raised a subscription to buy her an annuity that would provide a steady income.

Sarah Biffin did not ultimately go to America but stayed in Liverpool for the last years of her life. She died at her lodgings in Duke Street on 5 October 1850, just a few weeks short of her 66th birthday.

What I admire most about Sarah Biffin’s art is its precision. The clarity of detail, rich colours and her handling of light and texture give her subjects a lifelike air – you can almost see what they are thinking, and imagine them exchanging a few jokes with the gregarious and witty artist while they sit for her. With subtle shifts in colour and brushwork, and a deep understanding of the nuances of facial expression, she conveys the personality and humanity of people whose names are now mostly lost to us.

In her self-portraits, she often has a slight smile. She includes opulent fabrics, large hats and painting implements, suggesting a self-assured person confident of her place in the art world. She invites the viewer to see her as she is – not a fairground ‘eighth wonder’ but one of the most talented miniaturists of the 19th century.

Pigot’s Directory of Hampshire, 1830.

‘Instances of ingenuity under deprivations,’ Hogg’s Weekly Instructor, 17 July 1847.

The Morning Herald, 18 May 1830.

‘Miss Biffin,’ The Liverpool Mercury, 22 October 1847.