Thankful Taylor and the serpent within

In 1870s Tennessee, a young woman was reportedly afflicted by a snake in her stomach

Coiling itself around the fluid boundary between folklore and medicine, the legend of the ‘bosom serpent’ has revealed its fangs across many centuries and cultures. A snake – or sometimes a frog, newt or lizard – establishes residence in the stomach of its human victim, whose mistake has been to drink from a pond or stream.

Once there, the creature causes torment with its writhing and biting, leaving the sufferer on the verge of insanity or death. Questions fly round the local community: is the serpent real or imagined? Is the victim possessed or diseased? Remedies prove hopeless and the patient’s only option is to live in uneasy acceptance of the monster.

In most versions of the story, however, hope prevails. The serpent is removed – perhaps by a maverick doctor or folk healer – and the patient is at once restored to normal life.

The well-documented case of Thankful Taylor gives us a closer look at this phenomenon, and is unusual because a real snake exists, preserved by the physician who claimed to have extracted it from his patient in 1874.

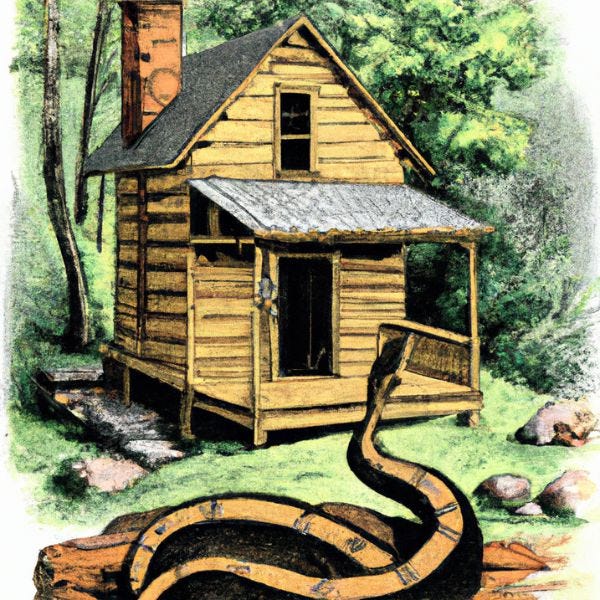

Louisa Taylor (b. 1852-d. unknown) was part of a large, poor family in Rutherford County, Tennessee. In the 1870s she was living with her mother, stepfather and about 10 siblings and half-siblings in a 16 x 18ft cabin near Christiana. The language used about her in newspaper reports suggests she had some form of learning disability and had experienced seizures from a young age. She was known as ‘Thankful’ to her family – a name that might have helped capture the public’s imagination after her deliverance from her unusual malady.

Her symptoms included abdominal pain and convulsions, after which she would ‘remain sometimes in a deathlike state for 24 or 36 hours.’1 Sometimes black mucus came up into her mouth, and her skin was prone to splitting. Local doctor Bartley N White (1841-1901) believed she had a tapeworm – a not uncommon occurrence in those living conditions. He tried for a year to treat her, but nothing worked.

On one occasion when Dr White wasn’t available, the family approached another physician, Dr Joshua M Burger (1837-1915), who announced that the worm was really a snake. He prescribed strong anthelmintics, but these only seemed to aggravate the creature. He anticipated that the snake would eventually appear in Thankful’s mouth and that she must be ready to grab it and pull it out.

On 26 June 1874, Thankful had the feeling that the ‘thing’ was preparing to travel up her throat. That evening, she suddenly got up and rushed outside; some 20 paces from the cabin, she dropped down and appeared to be choking to death. Her little brother spotted a dark loop in her mouth and, remembering the doctor’s instructions, her mother grabbed it.

When Dr Burger arrived, he immediately took hold of the loop and pulled out a living snake – 23 inches long and two-thirds of an inch in diameter. It appeared to have emerged from Thankful’s oesophagus and doubled back on itself, getting stuck. Thankful vomited several times and then recovered. The snake showed signs of life for a few minutes but soon expired.

There is no definitive explanation for what happened to Thankful or to the hundreds of other recorded cases of people believing they are afflicted by internal reptiles and amphibians. The ubiquity of parasitic disease in regions with poor sanitation does bring the fear of unwanted passengers closer to home; the idea that other types of creature could survive in the body is just a short leap. It’s easy to imagine that in some cases, a person might vomit up a roundworm and say it was ‘as big as a goddamn snake!’ leading rumours to begin.

Greg Tucker of the Rutherford County Historical Society, writing in The Daily News-Journal (Murfreesboro) in 2010, suggests that Thankful experienced pica – a condition in which someone has a compulsion to eat non-food substances – and had a habit of partially swallowing small snakes. In this explanation, she must have put the reptile into her mouth before the doctor arrived.2

Another possibility is that Dr Burger engineered the ‘cure’ by introducing the snake at some point during the confusion. He may have believed that Thankful’s symptoms were psychosomatic and would abate if she thought the creature had gone – such a trick would not be considered unethical at the time. The community’s admiration for the cure would bring in new business and might also have helped him get one over on Dr White, who had not been impressed when Burger took his patient.

Burger appears to have been acting in good faith and certainly went on to a long and respectable career, but there is an unsavoury element to his involvement. In partnership with local physician and businessman Dr L W Knight, he planned to take Thankful and the preserved snake on a tour of the northern states, where their story would attract paying visitors. This idea – fortunately for the vulnerable Thankful – did not come to fruition. Not much is known about her life after the snake episode, but in the 1880 census she is shown living as a servant with a local family.

During the three years after the snake’s emergence, the Rutherford County Medical Society and the Tennessee Medical Society held investigations. The former concluded that it was impossible for a snake to live in the human body and noted that Thankful was not, in fact, cured of her seizures; the latter did not rule out the truth of the story on the grounds that ‘according to the rules of sound logic it is not admissible to lay down the line of the possible in natural phenomena.’3

The ‘bosom serpent’ legend has appeared in many eras, places and cultures, offering a way for people to make sense of their genuine physical or emotional pain and to find the language to express it to others. Thankful Taylor had few advantages in life; whatever the explanation for her case, I hope her suffering decreased and that the departure of the snake gave her some peace to make the best of a difficult existence.

HistMed Highlights

THE OLD OP APOTHECARY SHOP: ☠️ 🪄 The Old Operating Theatre’s new online shop is open in time to find the perfect present for lovers of the weird and wonderful. Leech-jar earrings, macabre notebooks and anatomy tea towels are among this cool and quirky range of gifts.

OPIUM, PEPSI AND LEAD! 🫙Bristol Public Library in Connecticut shares patent medicine advertisements from the pre-FDA era at this free talk. 10am EST, 9 December 2023.

MADHOUSES OF THE METROPOLIS: 🚶🏾♂️🍎Take an analytical stroll through the evolution of psychiatry on Manhattan’s Upper East Side with author K. Krombie on this walking tour. 1pm EST, 3 December 2023 (other dates available), Carl Schurz Park, $36.

VITAL ORGANS: 🫀🦴 Author Suzie Edge presents The History of the World’s Most Famous Body Parts, exploring the stories of remarkable organs from Marie Curie’s bone marrow to Percy Shelley’s heart. This Christmas lecture at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh is at 6.15pm GMT on 7 December 2023, £10 and you get mince pies.

The Whig and Tribune, Jackson, TN, 11 July 1874.

The Daily News Journal (Murfreesboro), 14 February 2010.

Greg Tucker, ‘Bosom Serpent’, A Rutherford Snake.