The Brinkerhoff System

In 1877, Alexander W Brinkerhoff introduced an effective – and lucrative – treatment for piles.

If you wanted to make a quick buck in the late 19th-century US, becoming an itinerant healer had its appeal. Depending on your moral fibre (or lack thereof), you might sell a useful medicine and gain a good reputation, offer mysterious healing powers that convinced people they felt temporarily better – or you could make wild claims for an ineffective pill, trouser everyone’s cash and skip town before they could beat you up.

The Brinkerhoff System, launched in 1877, was a semi-reputable business investment for those who liked the travelling life and weren’t squeamish about adopting a real hands-on approach. For $200 (plus an ongoing 10% royalty on patients’ fees) the budding entrepreneur received a kit full of instruments, ointments, instructions on how to use them, and 100 copies of promotional leaflets titled ‘Glad Tidings’ and ‘Harvest Field of Death’.1

Everything needed, that is, to start a franchise operating on people’s haemorrhoids. (I’m sticking with my British spellings even when talking about the US.)

Haemorrhoids, or piles, are swollen blood vessels in the lower rectum and around the anus, prone to bleeding and causing discomfort. For patients in whom ointments had failed, the ‘clamp and cautery’ method of surgery was one option at this time. That involved drawing the pile out with forceps, clamping it to avoid haemorrhage and then snipping it off with scissors. The stump was sealed with a cauterising iron ‘so applied as not merely to sear the cut surface, but to thoroughly “cook” the whole projecting stump well up to the clamp,’ as Edmund Andrews relates in his Rectal and Anal Surgery (1888). He goes on to say the operation is not popular, because ‘the idea of burning the parts with hot irons is horrifying to the imagination of the patient.’ A more palatable – and in Andrews’ opinion, safer – method was ligature, i.e. fixing a silk thread tightly around the base of the haemorrhoid, causing it to drop off in about a week.2

Alexander W Brinkerhoff (1821-1887) was a self-made businessman and inventor living in Sandusky, Ohio. He never qualified as a doctor, but had plenty of experience as a patient. During his youth in the 1830s, repeated bouts of malaria had undermined his physical abilities and prevented him going into his intended trade of cabinet making.

Each recuperation period, however, gave him the chance to read every book he could get hold of; he became his community’s go-to source of knowledge. He taught at his local school for a while and enrolled in the Ohio Wesleyan University, but his health broke down again and he had to leave.

Brinkerhoff went on to build up successful mercantile and manufacturing companies – including the Ohio Fruit Jar Company, which sold his own patented design of glass container for making preserves. Renewed health setbacks in his 50s forced him to step away from his business and it ultimately failed, leaving him bankrupt in 1877. With a family to support, he needed a new way to increase his bottom line.

The idea to start curing people of haemorrhoids might not be an obvious one, but Brinkerhoff had a dog in the fight. He tells us in his 1881 book Diseases of the Rectum that he suffered from piles for 25 long years, and his experience taught him that doctors were not necessarily much help. One dismissed him with: ‘You can go to Philadelphia and get them cut out!’, while another held to the old assumption that piles were just a way for the body to get rid of excess blood.

Sclerotherapy – injecting the piles with a substance designed to shrivel them up – already had its place in the arsenal of treatments, but Brinkerhoff improved the procedure by patenting a rectal speculum that enabled the operator to see what he was doing.

‘The eye’, Brinkerhoff wrote, ‘affords more information than any finger!’ With the haemorrhoid in clear view through a sliding window in the speculum, he could accurately inject it with Brinkerhoff’s Pile Specific. According to Edmund Andrews, this preparation comprised carbolic acid, olive oil and zinc chloride.

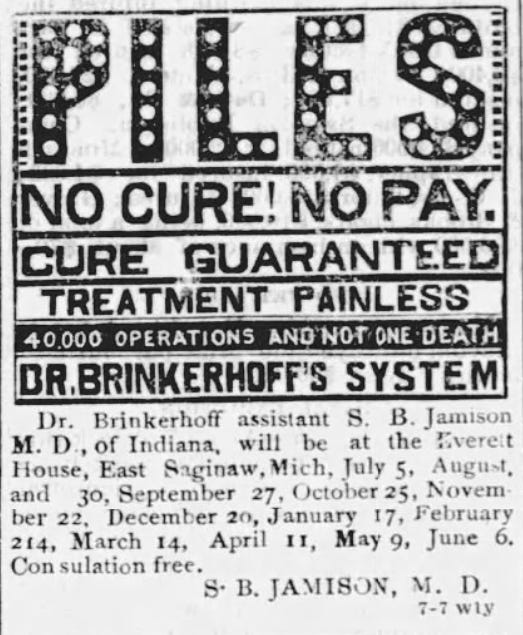

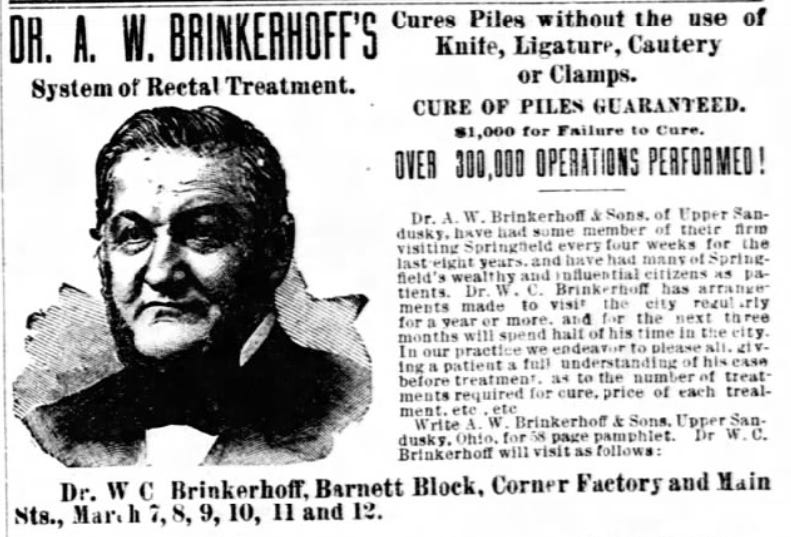

By 1882, advertisements referred to A W Brinkerhoff, M.D., and claimed that he had performed 40,000 operations. Just two years later, the advertised figure had increased to 80,000, and Joe Terry calculated in Bottles and Extras (Spring 2006) that if Brinkerhoff worked a 10-hour day, five days a week, he would be doing a procedure every 16 minutes!3

No wonder he wanted to get other practitioners in on the act. Selling the System as an off-the-shelf business opportunity increased its geographical range and fame, and gave him a steady passive income. Anyone with $200, an enterprising attitude and a steady hand could instantly become a pile-doctor, offering relief to the suffering sphincters of his local area. As well as the up-front payment and royalties, these practitioners had to keep buying the Pile Specific, Rectal Salve and other ointments direct from Brinkerhoff, who stipulated that his name should be used on advertisements.

The patient would not have all their piles seen to at once. One at a time, or perhaps two, was quite enough, with the pile-doctor returning 2-4 weeks later to do the next one – by which time the first should have fallen out. While Brinkerhoff’s promotional language and most practitioners’ lack of qualifications or experience put the scheme into the realms of quackery, the treatment did work and the rectal speculum was well-designed and useful.

Some reputable doctors purchased the System for use in their practices. Dr Miller of New York City, for example, wrote to the Medical Summary in 1886 to commend Brinkerhoff’s speculum and note that the System made piles ‘disappear as if by magic’ without the patient having to take time off business.4

Some, like Illinois physician Dr Layton, however, believed they had got a bum deal:

As to its being painless, I can say from positive experience that this is far from being the case, as I have had several of my patients hint at a suit for malpractice on account of such excruciating pain and soreness; so that I even forgot to ask them for my bill.5

Rectal ulcers required a different ointment – this time the carbolic acid was combined with ferric subsulphate solution, glycerine and witch-hazel. It was not even necessary for the patient to have a genuine rectal ulcer – pile-doctors allegedly diagnosed normal anatomical features as pathological, thus ensuring that everyone needed the treatment:

They generally show the patient’s friends the rectal fossa and term it a horrible eating ulcer, that is daily destroying the patient’s vitality, and which will sooner or later cause him to fill a consumptive’s grave. 6

This scene seems to involve a cluster of people gathering round for a peek at the patient’s hidden depths; at least the Brinkerhoff speculum gave them a good view.

Brinkerhoff died in 1887 and his sons took over the company – one of them, Willie, was a genuine doctor while his brother Milford had worked in the various family businesses since he was a lad. In 1892, they attempted to sue one Alfred Aloe for infringement of the speculum patent, but the court found that Brinkerhoff’s design was not as original as supposed; similar specula had preceded it without being patented.

Nevertheless, it is Brinkerhoff’s name that still graces this style of instrument today. The Brinkerhoff speculum is used in rectal examinations, enabling the proctologist to see any abnormalities and take a biopsy if required.

A W Brinkerhoff, Diseases of the Rectum, (1881).

Edmund Andrews, Rectal and Anal Surgery, with a description of the secret methods of the itinerants, (1888).

Joe Terry, ‘I’ll take patent pot-pourri for a thousand, Alex!’, Bottle and Extras, (Spring 2006).

E. P Miller, MD, ‘The Brinkerhoff Treatment for Hemorrhoids’, The Medical Summary: A Monthly Journal of Practical Medicine, New Preparations etc., (Philadelphia, PA, October 1886).

John Harvey Kellogg ‘The Brinkerhoff System’, Good Health, (Battle Creek, MI, June 1891).

The Medical Waif, quoted in Charles W Oleson, Secret Nostrums and Systems of Medicine, 1894.

I love your posts Caroline. So interesting. Keep ‘em coming!