The brittle man

A Norfolk man's rare condition puzzled doctors in 1910.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

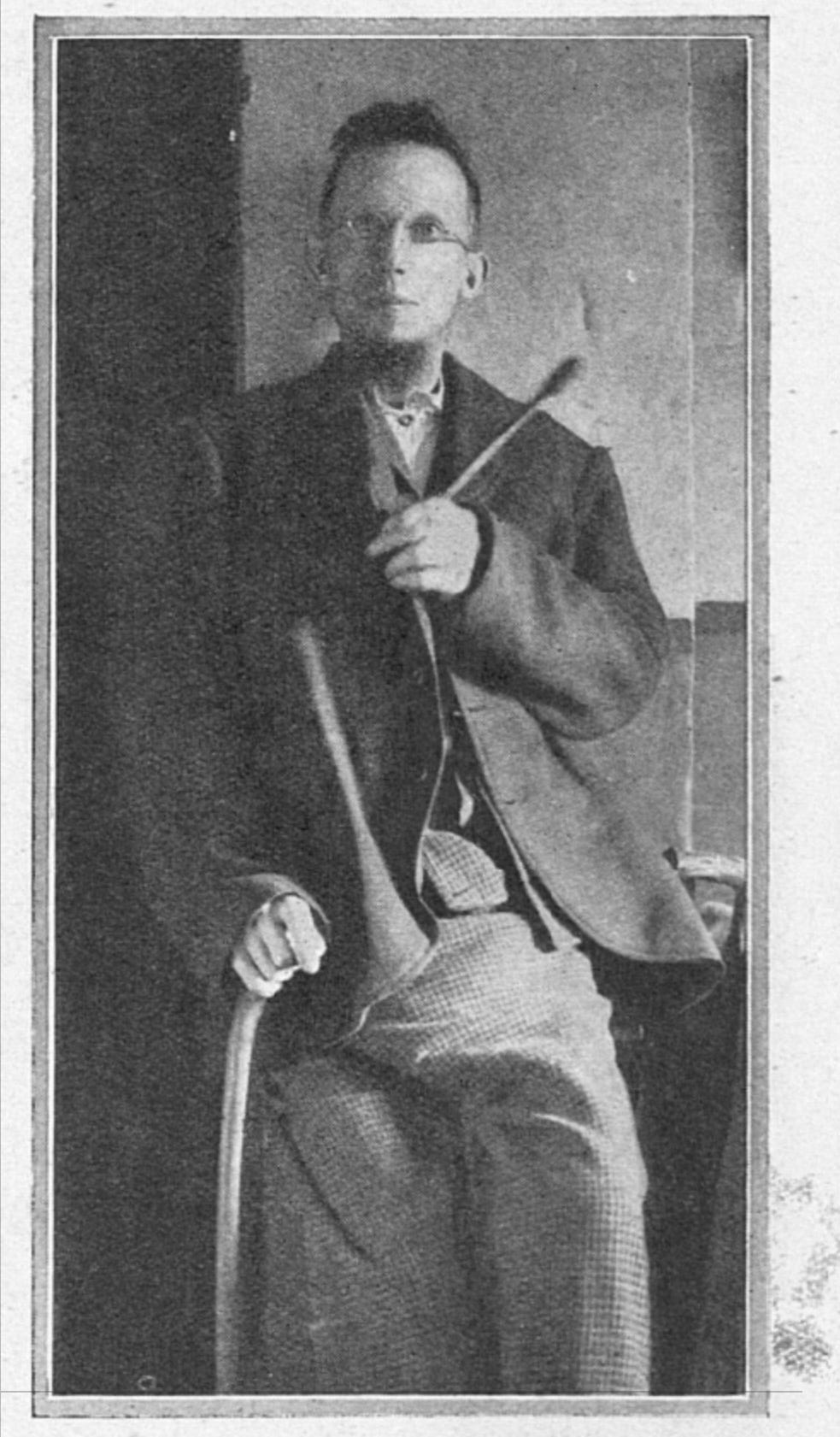

An honoured guest at most of the London hospitals is a tall, slim man, with a thin face, who has to move about with extreme care, because if he happened to fall down he might break in several places.1

In January 1910, a resident of the workhouse infirmary at Swainsthorpe in Norfolk travelled by train to London, where an ambulance arrived to convey him to the London Hospital. He had to lie flat in the railway carriage and, on reaching Liverpool Street station, the nurse who accompanied him ‘up-ended him’ onto his feet. Members of the public watched with curiosity as the ambulance attendants carried him to the waiting vehicle. He remarked that the city was ‘Cold—very cold!’

Alban Rushbrook (1867-1931) had an extremely rare disease known as myositis ossificans progressiva (now called fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva or FOP). Since the age of eight, his muscles had slowly been turning to bone and now, at 42, he was almost completely immobile. He had a small level of function in one arm, and in his lower jaw. The removal of some teeth had helped him get food into his mouth, and he was a keen pipe-smoker. He was able to use a pair of curling tongs to pick up his spectacles and put them on.

It is now known that this disease – which affects an estimated one in two million people – results from a spontaneous mutation in the ACVR1 gene. In Rushbrook’s time, no one knew what caused it. The London Hospital had offered to use ‘all the most modern developments of medical science at their command’2 to investigate and hopefully treat his condition.

The medical team started by taking x-rays, which showed that the ossification was a direct continuation from his skeleton, rather than isolated bony patches within the muscles. They next took a biopsy from his shoulder – something that is now avoided because it triggers rapid bone formation at the site.

One of the hospital’s methods of treating musculoskeletal disorders was by ‘Tyrnauer hot air baths’ – a German invention that had been donated by the Princess Hatzfeldt (who lived in Wiltshire) in 1909. This apparatus exposed patients to dry heat of up to 280°F (138°C) without pain or burning the skin. Rushbrook underwent the treatment with no effect. By April 1910 the hospital was no further forward in either discovering the aetiology or working out what to do about it, and had begun to see him as a ‘bed-blocker’:

‘There are 400 people waiting for vacancies,’ said a hospital spokesman, ‘and we do not feel justified in keeping the poor fellow here any longer.’3

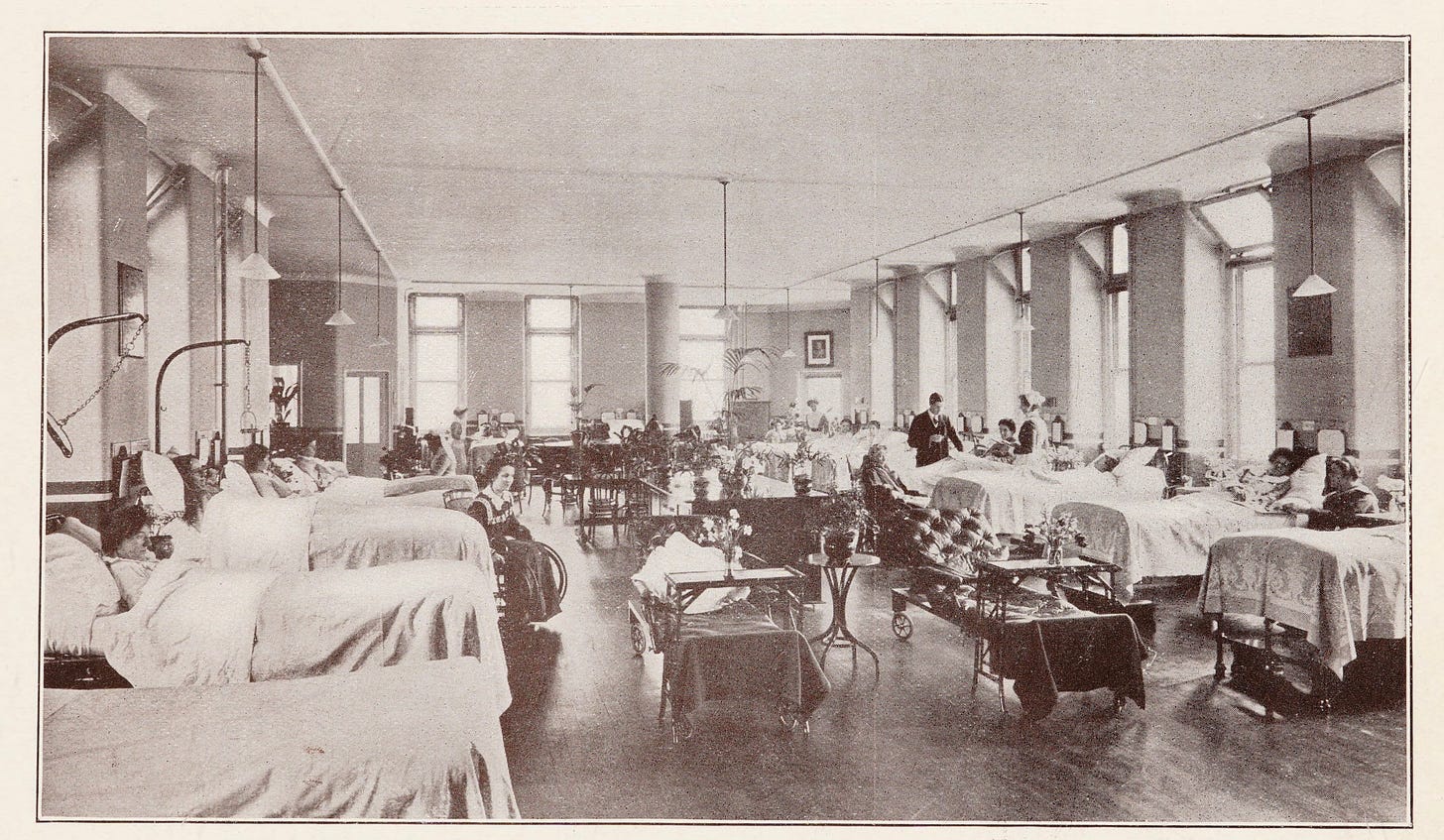

Rushbrook next went to the London Homeopathic Hospital in Great Ormond Street, where his treatment consisted of a few drops of thuja tincture once a month. While one might be sceptical about this, the hospital itself wasn’t a bad place to be – it had clean, warm wards and decent food, and Rushbrook did not undergo any invasive procedures that would make his condition worse. He believed he was improving and that the range of motion in his neck had increased, and he was able to spend a few months at the hospital’s convalescent home in Eastbourne.

Rushbrook seems to have approached life with hope and dark humour. While at the Homeopathic Hospital, he looked forward to Christmas because it was the only time he was allowed to smoke in bed, and to the summer when he would be able to go outside and smoke every day, but acknowledged that ‘the trouble is, I may be dead then.’

On a later occasion, he quipped to a newspaper reporter: ‘They say I’m to go in for the hundred yards race in the sports, with 99 yards start!’4

Ultimately, however, it was never going to be possible for him to get better. In early 1912, Rushbrook moved to St John’s Lodge Home in Raynes Park, Surrey, where he had been offered a place for life by the home’s founder and matron, Ada Sansome. He stayed there until his death in 1931, when he was 64 years old. He discovered a love of gardening and spent his days growing lettuce and tomatoes, using tools that he adapted to his requirements.

Ada Sansome was a former district nurse who set up the home as a place for people with incurable illnesses or disabilities to live in a safe and comfortable environment. Most residents or their families paid a small sum for their board, but there were also several ‘free beds’ for those without the means to pay. Otherwise, the Home relied on donations and fundraising events.

In a letter to the Pall Mall Gazette in May 1912, Dr Margaret L Tyler of the Homeopathic Hospital reported visiting Alban Rushbrook at St John’s Lodge and finding him in good spirits and enjoying the garden. Dr Tyler described the place and its matron in glowing terms:

Here was a little homely woman, with nothing, except genius and the love of God in her heart, bearing incredible burdens, simply bubbling over with homely wit and tender sympathy, doing the cooking and carving for the whole establishment – some forty souls – as she could not afford a cook!5

(This is the British sense of the word ‘homely’, meaning that she is unpretentious and welcoming – not that she is ugly!)

Nurse Sansome’s one aim in running St John’s Lodge, the doctor wrote, was to make the residents ‘as happy as may be for the rest of their lives.’ In the case of Alban Rushbrook, she seems to have succeeded, enabling him to enjoy the comfortable home in ‘an atmosphere of gaiety and cheerfulness and loving kindness.’

This is a fascinating piece and a testament to those in the 19th century keen to see even the poorest receive decent treatment.