The human hawks that prey upon their kind

A St Louis drug company sold mail-order morphine to desperate addicts.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Anti-quackery campaigner Samuel Hopkins Adams, whose articles in Collier’s Weekly exposed the grimmest excesses of the patent medicine business, reserved particular disgust for the purveyors of addiction cures. In September 1906, he wrote:

At the bottom of the noisome pit of charlatanry crawl the drug-habit specialists. They are the scavengers, delving amid the carrion of the fraudulent nostrum business for their profits. The human wrecks made by the opium- and cocain-laden secret ‘patent medicines’ come to them for cure, and are wrung dry to the last drop of blood.1

But at the same time, one of these addiction cure schemes was just getting started. Between 1906 and 1912, the Delta Chemical Company of St Louis, MO, made more than half a million dollars by supplying customers with exactly what they wanted. Unfortunately, that something was morphine.

Dr Robert Cook Prewitt (1879-1930) and Ryland Conwell Bruce (1866-1937) headed up the company. Prewitt had genuine medical qualifications from Barnes Medical College, but never had much success as a practising physician. He tried his hand at surgical instrument selling in Little Rock, AR, until this venture went down the pan. He then became a travelling salesman for various chemical companies and ended up working at the James Sanatarium, St Louis, which ran a mail-order addiction cure business.

Prewitt, in partnership with former insurance salesman Bruce, took over this business in around 1905-06 and started to think big. They traded as the Delta Chemical Company and dubbed their product Morphina-Cura, an ‘infallible remedy’ for drug habits of all kinds.

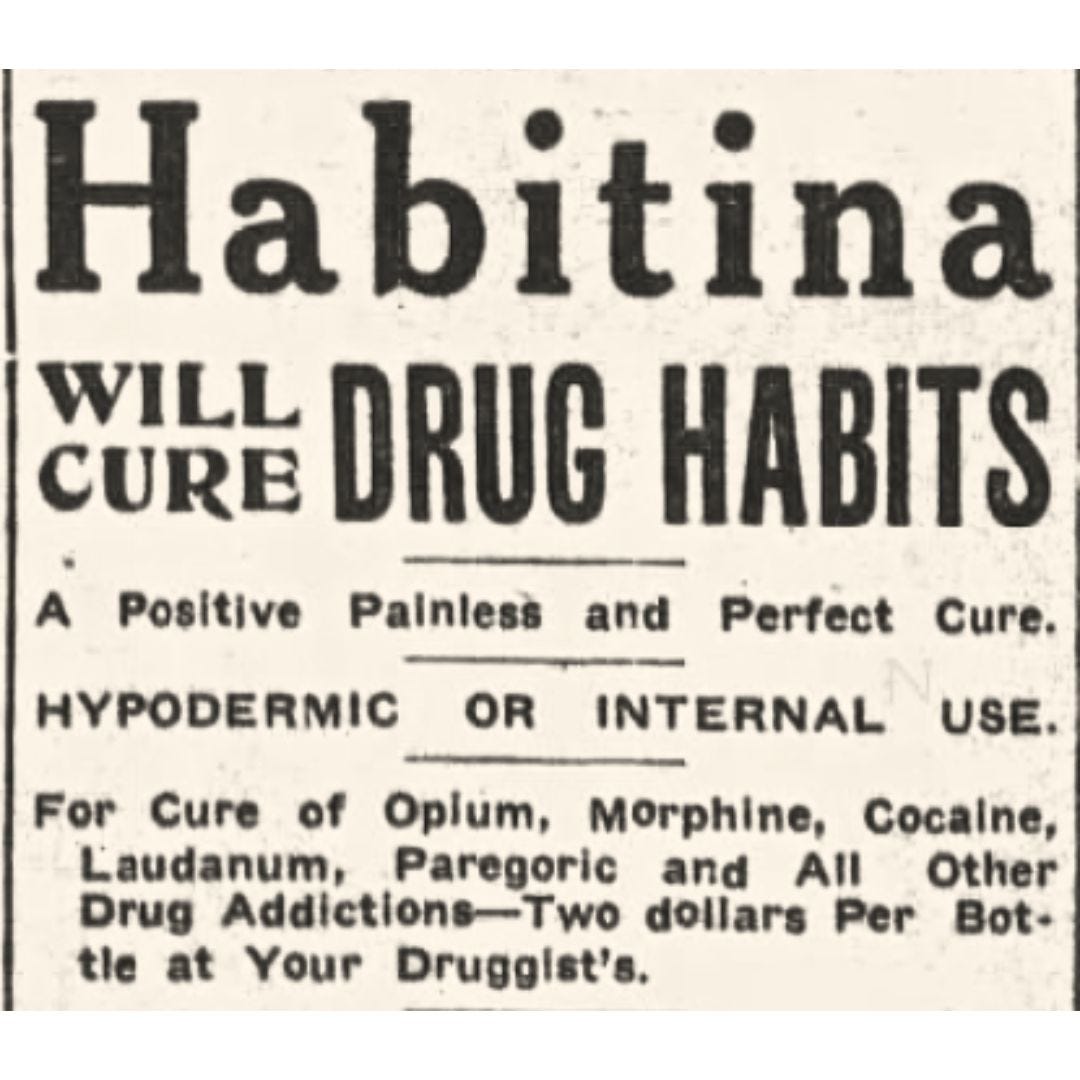

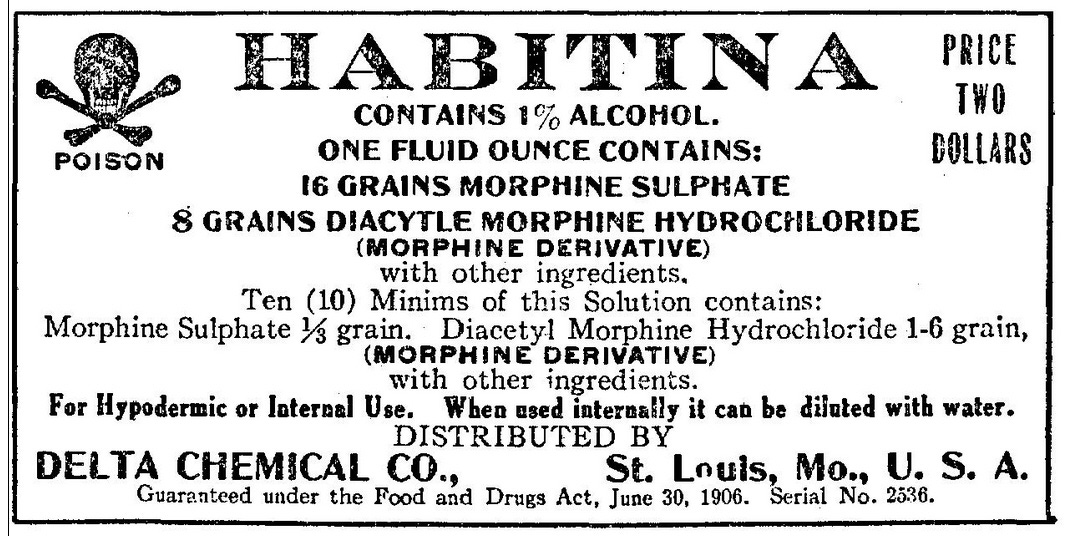

The product name changed to Habitina in 1907, probably because titling something a ‘cure’ could lead to allegations of misbranding under the Pure Food and Drug Act (1906). Addicts – often referred to as habitués at that time – were advised to ‘discontinue the use of all narcotic drugs and take sufficient HABITINA to support the system without any of the old drug.’2 They should then gradually decrease the dose until they stopped taking it altogether. As Habitina contained 16 grains (approx 1g) of morphine sulphate and 8 grains of heroin per fl. oz, ‘supporting the system’ meant preventing withdrawal symptoms by continuing the addiction.

Tapering off the use of an addictive drug was standard medical practice, and at face value the treatment sounds workable. The problem was that patients had no supervision and were left to follow the instructions – or not – as they saw fit. Indeed, if they didn’t manage to reduce the dose and just kept buying Habitina, that was healthy … for Prewitt and Bruce’s pockets.

The company hooked people in with free samples, and although they claimed to make patients answer a questionnaire, in reality they would send the freebies out to anyone who asked. The Journal of the American Medical Association pointed out that:

…under the present lax state of affairs, any man, woman or child who cares to go to the trouble of writing for this stuff can, at a total expenditure of two cents, get enough morphin to kill seven or eight people.3

In 1911, Robert Prewitt and Ryland Bruce were arrested and charged with sending poison through the mail and with using the mail for a scheme to defraud. Their trial in April 1912 revealed the devastating effect of Habitina on its victims, several of whom testified in court.

Harry Crocker of Poplar Bluff, MO, told how he became reliant on Habitina and lost his job and home. His former employer gave him some money to travel to St Louis in search of proper treatment, but he spent it all on the product.

‘When you were under the influence of the cure,’ he said, ‘you cared nothing for money, and wanted to give away all you had.’ The medicine made him ‘love the world’ and he took two bottles every day.4

His wife went to the Delta Chemical Company’s offices:

… and laid bare her life and that of her husband. She told how they had spent $5000 for Habitina, that her husband was a physical wreck, and asked for a few dollars for railroad fare to take them back to the old home. The managers ignored the woman’s words and told her they could do nothing for her, it is charged.5

Mr Crocker vowed to give up Habitina and devote his life to farming. He shut himself in his hotel room to go cold turkey, guarded by his wife.

Another victim was Grace M Shelby, ‘a young lady of good family,’ who had spent more than $2,300 on the drug over the past five years. She was already addicted to morphine and, when withdrawal symptoms prevented her from playing the piano at a party, someone offered her a bottle of Habitina. She could then play easily, and continued taking Habitina in a constant quest for the same results. By the time of the trial she had ‘sacrificed position, family, clothes, and has gone without shoes in order to obtain this drug.’

Mrs Minnie Potter, an African American woman from Pittsburgh, testified that Habitina had ‘destroyed her reason and made her absolutely blind.’6 She had since received hospital treatment and recovered.

Prewitt and Bruce were found guilty on both counts, fined $2,000 each and sentenced to five years’ hard labour. It would be nice to end on that note, but the pair immediately appealed and were released on appeal bonds. At the appeal court in December 1912, Judge Munger dismissed the count of sending poison through the mail, as registered physicians were still permitted to do this, and sent the second count – the scheme to defraud – to a new trial. It is not clear whether this second trial ever took place; Prewitt and Bruce do not appear to have gone to prison. The appeal judge pointed out that the product labelling was correct and buyers would be well aware of the medicine’s content.

While at liberty on the appeal bond, Prewitt officially changed his surname to Gregg because of his wife’s father’s will. Old man Gregg had stipulated that his daughter must keep her maiden name or forfeit her inheritance of $50,000. Her first husband went along with it without changing his own name, but Prewitt decided – either out of love for his wife or for the $50,000 – to become Robert C Prewitt Gregg. This must have had the handy side effect of helping to put his reputation behind him.

And what a reputation it was. Even before the arrests and court case, a journalist condemned such activities in colourful and dramatic terms:

Of all human hawks and buzzards that prey upon their kind, none is more deserving of execration than the “drug cure” quack. That celebrated object of odium, the man who set fire to the home for orphan babies, was no worse than this creature, who fattens by pandering with poison “treatment” to the cravings of the drug victims while pretending to aid him in his efforts to shake off the gyves the insidious drug has fastened upon him.7

Good article about pioneer drug dealers. I always enjoy reading The Quack Doctor posts.