The pin is mightier than the sword

Early 20th-century street harassers met their match in the humble hat pin

The trend of the ‘bumping man’ has recently gained attention on TikTok and in the mainstream British press. Well-established in Japan as butsukari otoko and now appearing in the UK, this phenomenon involves men deliberately colliding with women in busy city locations – sometimes knocking them over – and then melting into the crowd, free of all consequences.

Whether these ignoble wretches have the self-awareness to identify their own motivations, I don’t know, but their actions present as an assertion of power and resentment towards women; a way of hurting a woman without facing either arrest or the victim’s own retaliation. After all, people do sometimes bump into each other accidentally. If anyone challenges the assailant, he can claim that his silly victim wasn’t looking where she was going.

While contemplating how to design a bulky but wearable puffa jacket with outward-facing spikes concealed in the stuffing (maybe coated in the juice of a poison frog or something) I recalled a women’s self-defence phenomenon that swept the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – the hat pin.

Instead of the ‘bumper’, this period featured the ‘masher’ – an arrogant fellow who considered himself God’s gift but was essentially a common-or-garden street harasser. Some mashers were just annoying, trying to strike up flirty conversations with women minding their own business. Others stood on corners ogling female passers-by and making vulgar remarks. Some used crowded public transport as an excuse to press their bodies against their victims, and some escalated to violent sexual assault. All fell within the category of the ‘masher nuisance’.

A common explanation from police forces for their difficulty in quashing this nuisance held that women’s delicacy made them reluctant to appear in court – understandable, considering the publicity and the likely scrutiny of their character and actions by the defence.

Women’s delicacy, however, did not inhibit them from going straight for their harassers’ blood.

The hat pins of the time were around 12 inches long and went all the way through the hat, hair, and out the other side, where their exposed points were already hazardous enough to innocent people’s eyeballs. When a creep tried to grope her, the quick-thinking hat wearer could whip the pin out and drive it deep into his flesh. He would usually flee, with the wounds providing evidence if the police did catch up with him. If he later died of blood poisoning, well boo hoo.

Although the modern woman would probably risk jail for skewering an attacker with a foot-long spike, a 1902 case verified the hat pin as a legal weapon of defence. Dolly Tracy of St Louis, MO, appeared before Judge John C Robertson, having been arrested at the request of one Joseph Posten. Posten was miffed that she had been so unkind as to stick a hat pin in him – but neglected to mention that he had punched her just moments before.

‘I think you were justified in using the hat pin on him,’ the judge said. ‘If you had stabbed him a few times more I believe you would have done right’1 He fined Posten $10 for the assault.

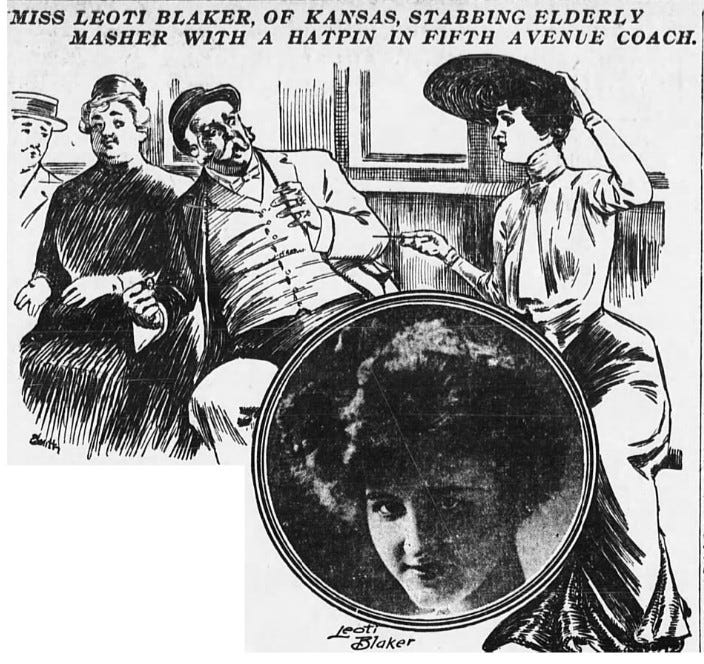

The following year, Leoti Blaker happened to sit next to a well-dressed, harmless-looking older man on a New York City coach. He began to behave lecherously and put his arm around her. This enraged her.

‘At last I reached up and took a hatpin from my hat,’ Miss Blaker told the press, ‘I slid it around so that I could give him a good dig, and ran that hatpin into him with all the force I possessed. Of course, all the time I was looking calmly in front of me, so that when he let out a terrible scream of pain no one in the coach had any idea what had happened.’2 The old perv bolted from the vehicle at the next stop.

In 1914, younger masher Daniel Sweeney faced the consequences of his actions in a gruesome way. He met 17-year-old Katherine Hermes at a dance on New Year’s Eve and offered to accompany her home.

‘While waiting for a car, we had one gin rickey apiece’, Miss Hermes said. ‘When we got off, the man assaulted me. He pushed me to the ground and I screamed, but he did not stop. In someway I got out one of my hatpins and I jabbed it into his body. I then got another one and he fled. I think I acted right.’3

Sweeney was fined $50 plus costs for assault and battery, but a worse fate loomed; the hatpin had punctured his heart. He continued going to work for the next week as blood oozed from a tiny wound, until one day he was found dead in bed at his lodgings. The coroner’s jury ruled the case ‘justifiable homicide’, and Miss Hermes was not arrested.

In the 1920s, the use of hat pins declined due to the fashion for bobbed hair, but of course the mashers hadn’t gone away.

New York City policewoman Mary Hamilton (who had become the city’s first female officer in 1918) headed up a ‘masher squad’ of plain clothes policewomen who posed as ordinary citizens and went about the shops looking out for dubious behaviour. Back-up came in the form of the ‘Sweet Williams’ – five male officers so nicknamed because they were all called William.

Although hat pins had become dated, Hamilton advised her officers to carry them and, if targeted by mashers, to ‘Scratch ‘em. Scratch ‘em hard’.4 The squad’s first arrest was a man who had been ‘accidentally’ pushing and falling against women in a railway carriage.

Which brings us back to our present-day bumping men. If this aggressive practice continues, it might be time to bring big hats and pins back into fashion.

Thank you for reading! It’s free to subscribe to The Quack Doctor, but if you enjoy my work and would like to contribute a small token of appreciation, please visit my Ko-fi page. Thank you!

‘Hat pin a legal weapon for women to deploy’, The St Louis Republic, 16 September 1902.

‘Stuck Hatpin into a Masher’, The Evening World (NY), 27 May 1903.

‘Death is result of hatpin stab’, The Green Bay Gazette, 16 January 1914.

‘“Scratch ‘em” is policewomen’s masher edict’, The Evening News (Harrisburg, PA), 14 March 1924.