The teeth stuck out like so many tusks

The case of a terrible set of dentures amused a court hearing in Victorian Wiltshire.

Chemist Henry Parker of Trowbridge, Wiltshire, advertised in 1852 that after much painstaking study, he had added dental services to his business. His new artificial teeth were warranted to restore the countenance of the wearer to apparent health and beauty, and to defy the detection of the most acute observer.

His problems began when a customer placed an order and he realised he would actually have to learn how to make false teeth – or find someone who could. The episode led to a legal dispute from which no one emerged well.

Dentistry at this time was unregulated, and any enterprising fellow could set up shop without knowing one end of a tooth from another. The more skilled practitioners – who had usually qualified as surgeons before specialising in teeth – despaired at the extent of quackery, but those who expressed their opinions in the medical journals were isolated voices in a fragmented profession.

Influential and knowledgeable dentists such as George Waite MRCS and James Robinson, pioneer of anaesthesia in the UK, advocated for formalised training but there was a long way to go. Robinson’s short-lived journal The Forceps summarised the situation in 1844:

'In this country any quack who chooses to place a brass plate on his door, some artificial masticators in his window, and advertises his list of charges in the papers is a dentist to all intents and purposes.'1

The public often had no choice but to consult some random with a reputed knack for dentistry – whether that be an itinerant practitioner pulling out teeth in front of an audience, a local blacksmith doing dentistry as a sideline, or a druggist like Henry Parker offering this service in his shop.

Parker initially approached a false teeth maker named John Wood, but when a suitable set wasn’t forthcoming from this person, he turned to Charles Ballinger of Bath. Both Wood and Ballinger called themselves ‘mechanical dentists’, which meant they produced artificial teeth but did not do the surgical side of things. Parker agreed to pay Ballinger £7 15s to make the dentures and he would then charge his client £12. The pair visited the lady at home to take an impression of her mouth and returned with the new teeth just a few days later. They did not, however, fit:

'The lady's mouth would not close; the front teeth were all inside of the jaw, and eating or speaking was out of the question.'2

Ballinger amended the set and tried again, but with no success:

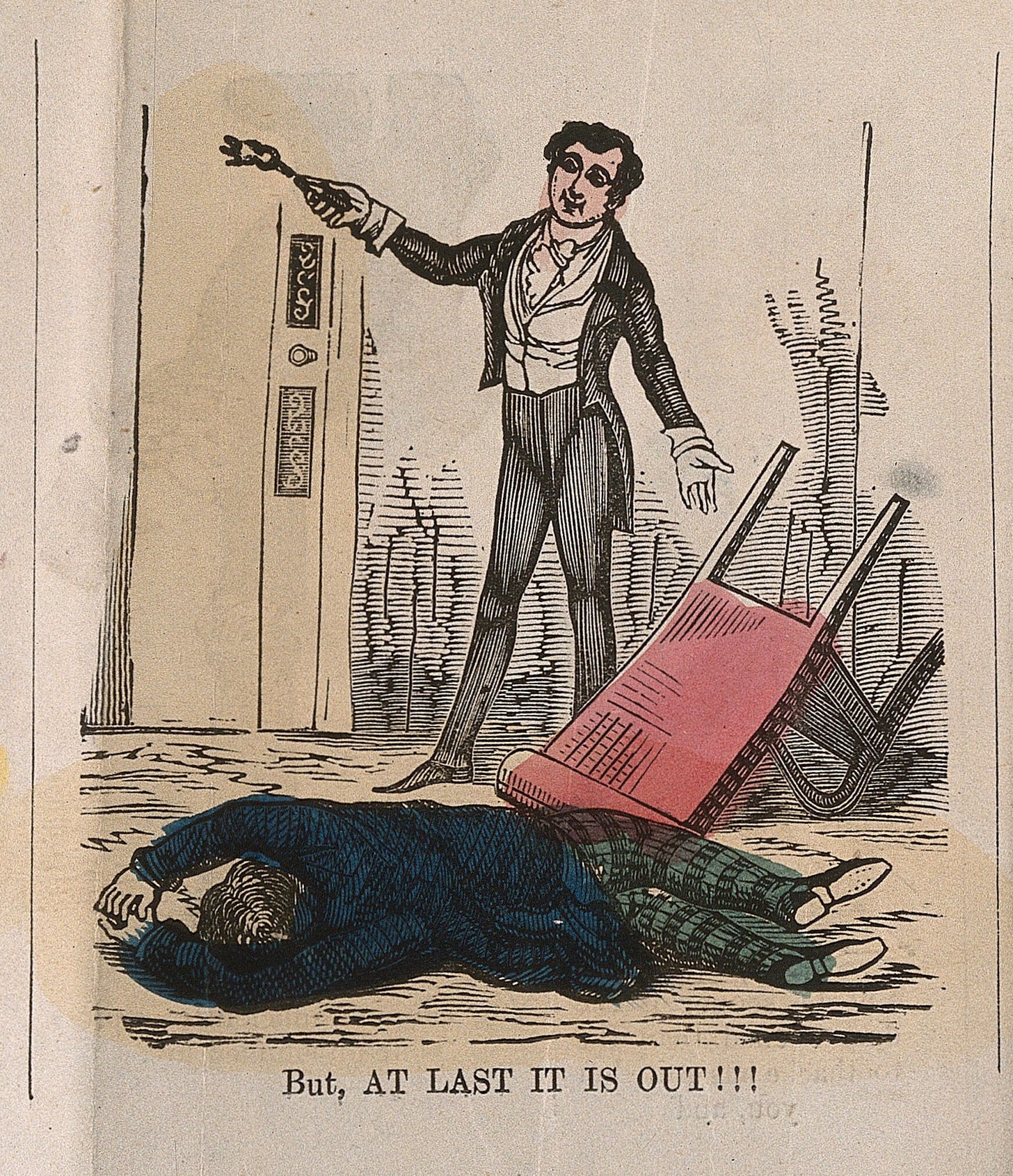

'The change was wonderful. In addition to the mouth being kept wider open than before, the teeth stuck out like so many tusks, making the patient a perfect fright. It was now discovered that the fault was in the mouth and not in the teeth.'

A third attempt hit the limit of the lady’s patience and, having had the teeth repeatedly shoved into her mouth in a ‘truly pitiable’ manner, she called time on the whole episode and declined to buy them.

Parker, in turn, refused to pay Ballinger, so Ballinger took him to court. The hearing attracted spectators hopeful of some amusement from such a ridiculous-sounding case, and they were rewarded by the performance of a witness, John Wood – the mechanical dentist whom Parker had had dealings with before. Wood, a former cabinet maker, was an elderly man whom the Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette described as ‘quite a character’. He had made no fewer than 18 sets of teeth for himself and wore a different one each day. He demonstrated this to the court by whipping out his gnashers and holding them up, saying 'Now look, look at me!' Observers were astonished to see that 'the old man's nose and chin almost met when deprived of his teeth.' He popped them back in and volunteered to demonstrate their quality by cracking nuts, but was stopped by the magistrate.

Wood approved of Ballinger’s work, saying that he had made a ‘capital set’ that should be worth about nine or ten pounds.

Wood's evidence does not seem to have added much to the proceedings beyond entertainment, but a more reputable dentist called Mr Ayton examined the dentures made by Ballinger and discovered that all the teeth, whether front or back, were the same. They 'displayed on the part of the maker total ignorance of the practice of dentistry.'

Ballinger admitted that he was not a dentist, but a jeweller who had lately started making false teeth. Neither he nor Henry Parker had covered themselves in glory, and the magistrate dismissed the case, ordering both participants to pay their own costs.

The unnamed lady, who had patiently put up with their incompetence, would have to look elsewhere for her new smile.

From The Quack Doctor archives

Health Grains: a fortune built on sand

Mrs Bertha Bertsche, a 38-year-old widow, could often be found supervising the pans on the kitchen range at her home in Glebe Avenue, Westchester Square, New York. Inside the pans, however, was no hearty stew or bubbling jam. At the request of her lodger, Jacob Selzer, Mrs Bertsche was using the range to dry a substance of very little culinary appeal.

Selzer’s new venture in the world of patent medicine brought his ‘Health Grains’ to the market as a cure for indigestion. The American Medical Association found that ‘when ground between the teeth they exhibit unmistakable signs of hardness’ - for reasons that you can probably guess.