Theriac: ancient miracle or modern mirage?

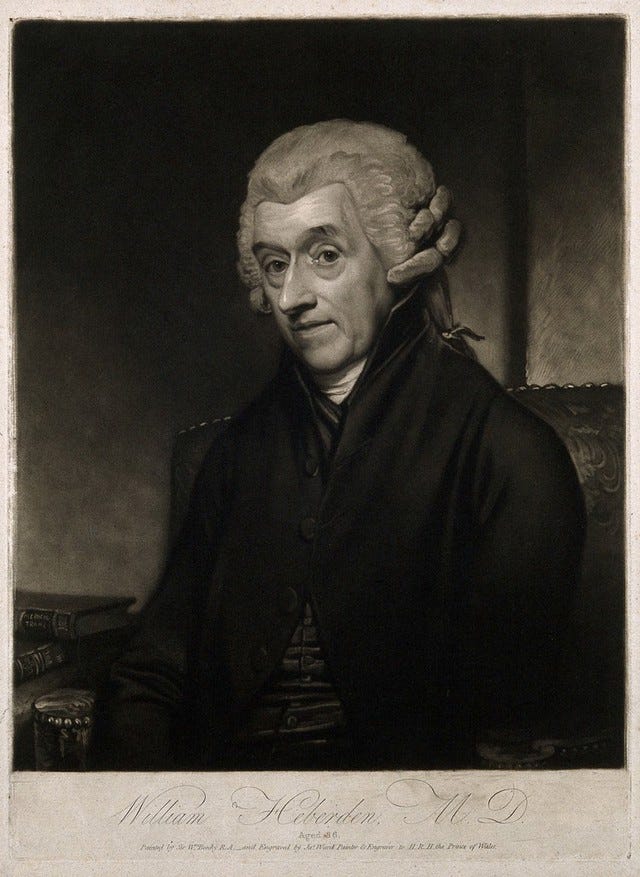

The illustrious history of this multi-ingredient panacea didn't convince 18th-century physician Dr William Heberden.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Londoners could visit apothecary Richard Stoughton at the Unicorn in Southwark and spend 3s 6d on a pot of Venice treacle. The pots were guaranteed to have been transported unopened from Italy and to contain only the best quality ingredients. This was not, however, the sticky molasses we would now associate with the word 'treacle', but an iconic panacea – also known as theriac – with its origins in antiquity. Traditionally containing over 60 ingredients, including viper’s flesh and opium, it began as a reputed antidote for poison and evolved into a treatment and preventive for hundreds of diseases.

Some, however, were sceptical of its miraculous powers. In 1745, Dr William Heberden elegantly debunked the myths surrounding theriac in his essay Antitheriaka.

The forerunner to theriac was said to have originated in ancient Pontus – a kingdom on the shores of the Black Sea in what is now Turkey. Its ruler, Mithridates VI (135-63BC), faced the usual royal problem of everyone wanting to kill him and seize power. As a young man, he could not even trust his own mother, who favoured his brother for succession. The threat of poisoning permanently hung over him.

Mithridates set out to neutralise the threat by taking small, gradually increasing doses of the poisons likely to be used against him. He then took this further and was credited with creating mithridate or mithridatium – a medicine that combined all known antidotes in one potent formula.

As wonderful as it sounds, this concoction had its disadvantages. Legend had it that when Mithridates did feel the need to end his life in the face of defeat by the Roman army and a rebellion led by his son, he couldn’t poison himself and had to get his bodyguard to stab him. According to Appian of Alexandria’s Roman History, he poetically proclaimed:

‘Although I have kept watch and ward against all the poisons that one takes with his food, I have not provided against that domestic poison, always the most dangerous to kings, the treachery of army, children, and friends.’1

Following the king’s death in 63BC, the recipe for the antidote fell into the hands of the victorious Romans. In the first century AD, Emperor Nero's physician Andromachus developed it into a 64-ingredient composition called galene ('tranquillity'), which later became known as theriac. Important to its composition was the flesh of vipers, which were thought to have special properties that kept them safe from their own venom.

Scepticism about theriac started early. The natural philosopher Pliny the Elder (23-79AD) thought the complex formula ‘…clearly must emanate from a vain ostentation of scientific skill, and must be set down as a monstrous system of puffing off the medical art.’2 A hundred years later, however, Galen was more enthusiastic, and his influence helped to cement theriac's popularity. He made it for the Emperor Marcus Aurelius; it took around forty days to prepare, and ideally should be aged for twelve years, but Marcus was a keen theriac-taker and preferred to consume it within a couple of months.

Via the Silk Road, theriac became important to Arabic and Chinese medicine as well as to the Europeans. By the twelfth century, Venice was a leading exporter and, in England, the substance became known as Venice treacle (a corruption of 'theriacal'). It was a prominent line of defence when the Great Plague hit London in 1665.

But theriac's fortunes would eventually wane. Dr William Heberden (1710-1801), was a physician and classical scholar whose contributions to medicine include his descriptions of angina pectoris (1768) and ‘Heberden’s nodes’ – the bony swellings that form around the distal interphalangeal joints in osteoarthritis. In 1745, he published Antitheriaka: an essay on Mithridatium and Theriaca, arguing that theriac preparations were not medicinally useful.

His view was that, after the defeat of Mithridates by Pompey the Great, some enterprising Romans cashed in on his reputation as a powerful leader by inventing a complicated recipe for Antidotum mithridatum and claiming it had been found among the king's papers. Once released into the wild, this legend ‘was carried to a much greater height by that strong passion which the Vulgar have ever shown for prodigies and miraculous stories.’3

Heberden tackled the ‘appeal to antiquity’ fallacy by arguing that other traditions were recognised as false:

‘Would it not be as strange to make use of [these antidotes], as of the charms and amulets which are delivered down to us as preservatives from witchcraft, an evil eye, or the power of any malicious Demons?’

In Heberden’s opinion, the sheer number of ingredients in mithridatium and theriac was unreasonable. He pointed out the potential for adverse drug interactions, and that one dose would contain so little of each substance that there could be few therapeutic effects.

Besides which, the recipe didn’t stay the same for any length of time: the Roman writer Celsus had described a 38-ingredient mixture, while Pliny mentioned 54, Andromachus famously used 64, and later writers had taken some substances out and added others in depending on geographical availability. Repeatedly passing on the recipe through many centuries allowed errors to creep in, while some original botanical ingredients could have been misidentified or died out since ancient times. Theriac could be pretty much anything. As long as it contained opium, people would use it, so there was no point in all the other stuff and the elaborate compounding procedure was, as Pliny had recognised, just for show.

If theriac were simply useless, Heberden believed, it would not be worth much attention. The inconsistency of its composition, however, made it dangerous – the opium content could be unevenly distributed, leading to minimal opium in one part of the jar and a fatal dose in another.

In a final reference to the ancient days of Mithridates VI, Heberden compared theriac to a barbarous king’s undisciplined army: ‘made up of a dissonant crowd collected from different countries, mighty in appearance, but in reality an ineffective multitude, that only hinder one another.’

After this debunking, theriac was removed from the London Pharmacopoeia but remained in some continental European pharmacopoeias until the late nineteenth century. Informal use of theriacs persisted longer – in 1915, a British newspaper columnist named 'Whist' wrote that he had been told in Touraine that it was still in use among the 'ignorant peasantry yonder'. He noted that using viper’s flesh as an antidote to viper venom was ‘an early application, as it would seem, of the doctrine of homeopathy – the doctrine that “like cures like”’.4

HistMed Highlights

Poisons, Potions and Pills: The story of Victorian Pharmacy

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret, 25 January 2024, 6pm, £15.

Between the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign in 1837 and her death in 1901, scientific approaches completely changed our knowledge of illness and its treatments. Nick Barber, Emeritus Professor at UCL School of Pharmacy and presenter of the BBC’s Victorian Pharmacy, will take you through the momentous six decades that saw the professionalisation of pharmacy, the move from herbal to more chemical products and the start of the pharmaceutical industry.

A Spoonful of Opium Helps the Medicine Sell Faster

Check out this fascinating online exhibit curated by Brooke Patten of Christopher Newport University. Using artefacts from the Isle of Wight County Museum in Smithfield, VA, the exhibit explores the origins of pharmaceuticals in early American medicinal practices, the roles of doctors and pharmacists in the 19th century, and the hazards of unregulated patent medicines that led to U.S. legislative action to protect consumers.

Appian, Roman History, The Mithridatic Wars, 23, 111.

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book 29: Remedies derived from living creatures, tr. John Bostock and Henry T Riley, 1857.

W Heberden MD, Antitheriaka: an essay on mithridatium and theriaca, 1745.

‘Whist’, ‘Looking around,’ The Newcastle Journal, 24 March 1915.