Turning heads: the Victorian fashion for mechanical hair-brushing

Hair-brushing by machinery became all the rage in 1860s Britain

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from the history of medicine and related themes.

It’s free to subscribe, but if you would like to make a one-off contribution to the coffee supplies that keep me going, please go to my Ko-fi page here. Thank you!

Brushing one’s hair might seem a mundane activity, but the 1860s brought an exciting new twist to this daily ritual.

Hair-brushing machines – promising efficiency, luxury, and even some comic potential – became a sensation at a time when the mechanisation of everyday activity spoke of prosperity, progress and improvement to the human condition.

The hair-brushing phenomenon began in 1862, when 35-year-old Bristol hairdresser Edwin Gillard Camp received a patent for his innovation – a rotary hair brush set in motion mechanically and guided around the customer’s head by a skilled operator. The Dundee Courier gives a detailed explanation of how it worked:

The party whose hair is to be tittivated sits beneath an india-rubber endless band revolving on a wheel attached to a shaft, which is driven by a large fly wheel in an adjoining room. The brush is circular and hollow, and is placed on a short shaft having two handles, and fitted with a grooved wheel at one end. This wheel is placed on the band, and revolves with a slow and steady motion. The brush is then gently carried all over the head, thoroughly cleansing the scalp, and imparting an agreeable feeling.1

The original machine was aimed at men due to the likelihood of its brushes getting tangled in women’s long hair, but this problem was solved in 1865 by Neat & Co of Southampton, who added another pulley on the floor, allowing the brush to be drawn downwards in one long sweep. Neat & Co advertised its power to alleviate headaches as well as improve one’s appearance.

Camp’s American patent, issued two years after the British one, is available online and gives a more technical description. Its inventor did not insist on any particular type of power source, but in 1868, a Punch cartoon passed comment on the likely reality – child labour.

Steam power, however, was another option, or a turbine water engine such as that installed by Sturrock and Sons, Glasgow. Clements and Shipwright of Tichborne Street, London, used a half-horsepower Lenoir Gas Engine in 1865 – quite necessary, since they claimed to be brushing 1,000 heads of hair a week.

These hairdressers were among a purported 2,000 who applied to Camp for a license to use the machine between 1862 and 1864. Purchasing one and adapting the shop could cost around £45, so it was not something to be tried out on a whim. After installation, the hairdresser was also required to pay a royalty of £1 11s 6d every six months to Camp during the lifetime of the patent. Thus they were keen to get punters in – advertisements announced the arrival of the machine to salons all over the country, emphasising its novelty and its superiority over old methods.

‘A new sensation. Everybody is delighted,’2 announced D. M. Allan, Dundee, while James Scott of Newcastle-upon-Tyne said it ‘is unmistakeably the greatest Luxury of the day, and is acknowledged by Thousands as the desideratum of the Age.’3

The notion of mechanised hair-brushing had great potential for amusement, which spread beyond the pages of Punch and reached the stage. A blackface performance group, the ‘Star Minstrels’, included in their repertoire a sketch called ‘Hair-brushing by Machinery’, which ‘produced the most uproarious mirth and screams of laughter’4 at Liverpool in April 1864, and was similarly well-received for the rest of the tour.

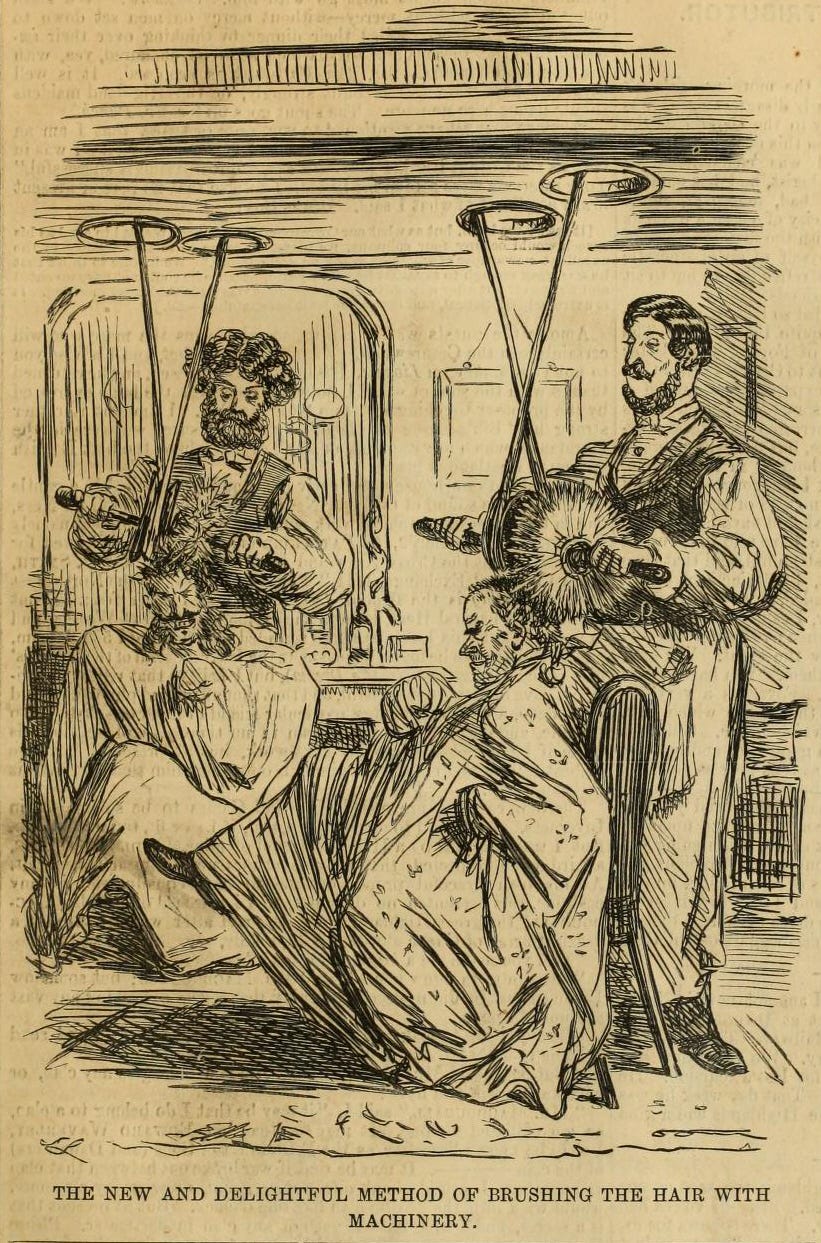

Another Punch cartoon (above) presents the process as rather an ordeal, but a description in Chambers’s Journal in 1863 gives the opposite view, placing the experience in a pleasurable, indeed sensual, light:

When I went in to get my hair brushed, had sat down before the glass, and been tucked in as usual, with bib and dressing-gown, the hair-dresser took up one of his circular brushes and hitched it to the revolving band over my head. In a moment I felt a silent fanning, as if some monstrous butterfly were hovering over me; this was the air of the twirling brush, which caught my hair up and laid it down, and travelled all over my head with incessant gentle penetration. It crept down my whiskers and searched my beard with the same tender and decided effect. There was no scratching, not even of the neck and ears, but the skin of cheeks and chin was reached and swept. It was a new sensation. I felt as if I should like to be brushed continuously for a month.5

The feelings of wellbeing, however, did not necessarily extend to the person doing the brushing. As the purpose of brushing was to clean the hair rather than simply untangle it (marketers had not yet capitalised on the idea of persuading everyone to use shampoo every day), the brush removed ‘extraneous matter’ from the scalp. This had to go somewhere, and in a lecture in 1876 Dr B W Richardson reported his friend Dr Cholmeley’s hypothesis that the dust was responsible for respiratory disease in hairdressers.6

According to J T Arlidge in The Hygiene and Mortality of Occupations (1892), however, the new machine was not to blame for the ill health of its operators – that was more likely to be attributable to their ‘loose habits of life’ and the ‘effeminate nature of their occupation’.7