'You cannot prevent me from becoming a dentist!'

Lilian Lindsay (1871-1960) overcame opposition to qualify as the UK's first female Licenciate in Dental Surgery

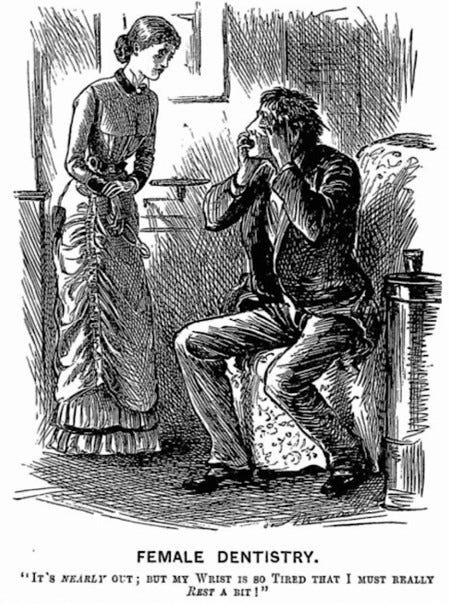

When the committee of the National Dental Hospital in London resolved to allow women to train as dentists there in 1887, the London Echo’s columnist ‘Man About Town’ initially reacted with surprise. On further reflection, however, he considered the advantages of lady dentists – they would ‘coax out’ teeth rather than yanking them, and the hospital’s neighbours might enjoy more peace and quiet, because:

…full-grown men will be ashamed to set up a yell that can be heard half a mile off when a gentle, dark-eyed girl, with a delicate wrist and a pensive smile, says “Hold still; I shan’t hurt you.”1

The Journal of the British Dental Association cautiously welcomed the development. While concerned that dentistry would be too physically strenuous for some women, they did acknowledge that the profession should keep up with medicine, and that there was a strong demand for female practitioners in India.

Women interested in becoming doctors but put off by ‘certain conditions naturally distasteful to them’ could find a good compromise in dentistry, where one did not have to examine anyone’s nether regions. The Journal also trusted women not to be too ambitious. Unlike male dentists, who worked too many hours in pursuit of wealth, women would sensibly take time for repose.

I am not sure quite what happened to the National Dental Hospital and School’s enlightened outlook over the next few years, because when 21-year-old Lilian Murray (remembered now as Lilian Lindsay, which I will call her for the sake of consistency) applied for admission in 1892, she was rejected due to her sex. The Dean, F. Henri Weiss, refused to allow her across the threshold.

Lindsay’s path to becoming a dentist had begun as a form of rebellion, and she would need every facet of this attitude to see her through the challenges of qualifying. Her headmistress at the North London Collegiate School insisted that she should become a teacher, and was enraged at her pupil’s lack of interest. ‘Then I will prevent you from doing anything else,’ Miss Buss said, and got the defiant response: ‘You cannot prevent me from becoming a dentist.’2

‘I knew nothing of dentistry,’ Lindsay wrote in an autobiographical sketch later in her life, ‘but having stated boldly that I would be a dentist, there was nothing else to be done.’

Encouraged by her mother’s friend Dr Olga von Oertzen, who qualified in Philadelphia and practised in London, Lindsay completed a three-year apprenticeship in a dental workshop and passed the preliminary examination to register as a student. Although Henri Weiss turned her away, he did advise her that the head of Edinburgh Dental School might feel differently.

Lindsay wrote to Edinburgh’s Dean, William Bowman MacLeod, and received the promising reply: ‘Women are received on the same footing as men.’ So off she went to Scotland in the autumn of 1892.

Once installed in an austere bedsit in Edinburgh and having been to see Mr MacLeod (who remained supportive), Lindsay went to pay her course fees. The treasurer tried to dissuade her from enrolling. When he saw how determined she was, he relented a little, but suggested just paying for the first three months, because: ‘you will be sure to give it up as you do not know what you are in for and will be sorry when you find that no money is returned.’

Lindsay half expected there to be other female students in her year; there weren’t. Her arrival caused some amusement for the tutoring dentist, but her male classmates accepted her at once and she made many friends during her time there. On that first day she met Robert Lindsay, whom she would go on to marry.

One argument against the training of female dentists held that they would take jobs that should rightfully go to men. Lindsay encountered this attitude first-hand at Edinburgh when surgeon Sir Henry Littlejohn told her: ‘I’m afraid, madam, you are taking the bread out of some poor fellow’s mouth.’

But she worked hard and excelled in her studies, winning prizes for dental surgery, pathology, materia medica and therapeutics in 1894. Although she faced many challenges – including lack of money, difficulty accessing surgical lectures, and an exhausting stint as a Medical Mission locum among those living in extreme poverty in Cowgate – Lindsay was resilient and determined.

‘…it was part of the road I had to travel,’ she wrote, ‘and believing that the merry heart goes all the way, I enjoyed those years to the full.’

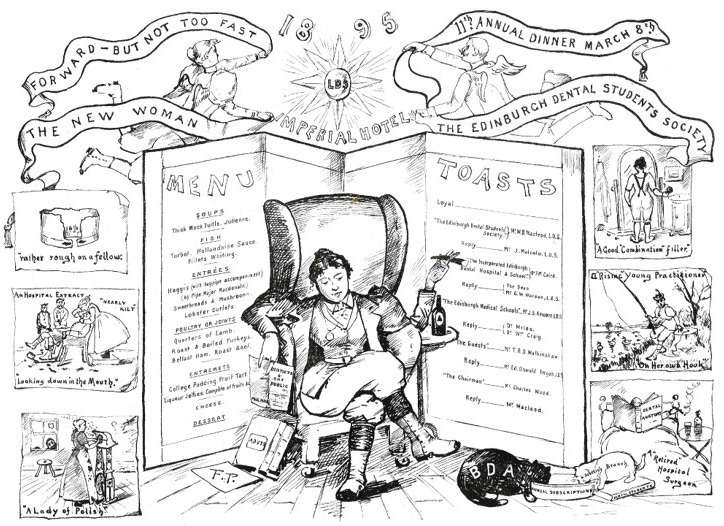

In 1895 she passed her final examination and became the first woman to receive the Licence in Dental Surgery. A menu card for The Edinburgh Dental Students’ Society annual dinner that year celebrates her achievement, characterising her as a self-possessed heroine, wearing breeches and smoking a cigar.

‘The students, without exception, had treated me as one of themselves and I do not think there could have been a kinder or finer set of young men,’ she wrote.

After graduation, Lindsay set up her own dental practice in London, starting out on a shoestring but successfully building up her client base. Her mentor Dr von Oertzen died and left Lindsay her business. In 1905, ten years after qualifying, Lilian and Robert finally had the means to get married, and they moved back to Edinburgh to run a practice together.

In 1920, Lilian Lindsay became the first female member of the British Dental Association Council, and would go on to be the organisation’s first female president in 1946, the same year that she was appointed CBE.

When she retired from clinical practice, she developed a strong interest in the history of dentistry and published an English translation of an important early text, Pierre Fauchard’s Le Chirugien Dentiste (The Surgeon Dentist), as well as her own A Short History of Dentistry and numerous papers. As honorary librarian to the BDA, she curated its collection of books and artifacts, creating the foundation for the organisation’s extensive library and museum.

Lindsay’s path from rebellious schoolgirl to revered dentist and historian not only shattered barriers in her own time but also laid a foundation for future generations of women in dentistry. Today, the British Dental Association’s Robert and Lilian Lindsay Library, and the Lindsay Society for the History of Dentistry pay tribute to her pioneering spirit.

Thank you for reading! It’s free to subscribe to The Quack Doctor, but if you enjoy my work and would like to contribute a small token of appreciation, please visit my Ko-fi page. Thank you!

‘Lady Dentists’, article from the London Echo reproduced in the Northern Weekly Gazette, 22 October 1887.

E M Cohen and R A Cohen, ‘The Autobiography of Lilian Lindsay (annotated)’, Dental History, 23 November 1991.

Thank you! This is well written and a rather wonderful story of resilience.