A grave scandal: the sale of corpses in 1857

A quarter of a century after the Anatomy Act, dodgy characters were still making money from the illicit sale of the deceased poor.

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from medicine’s past. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

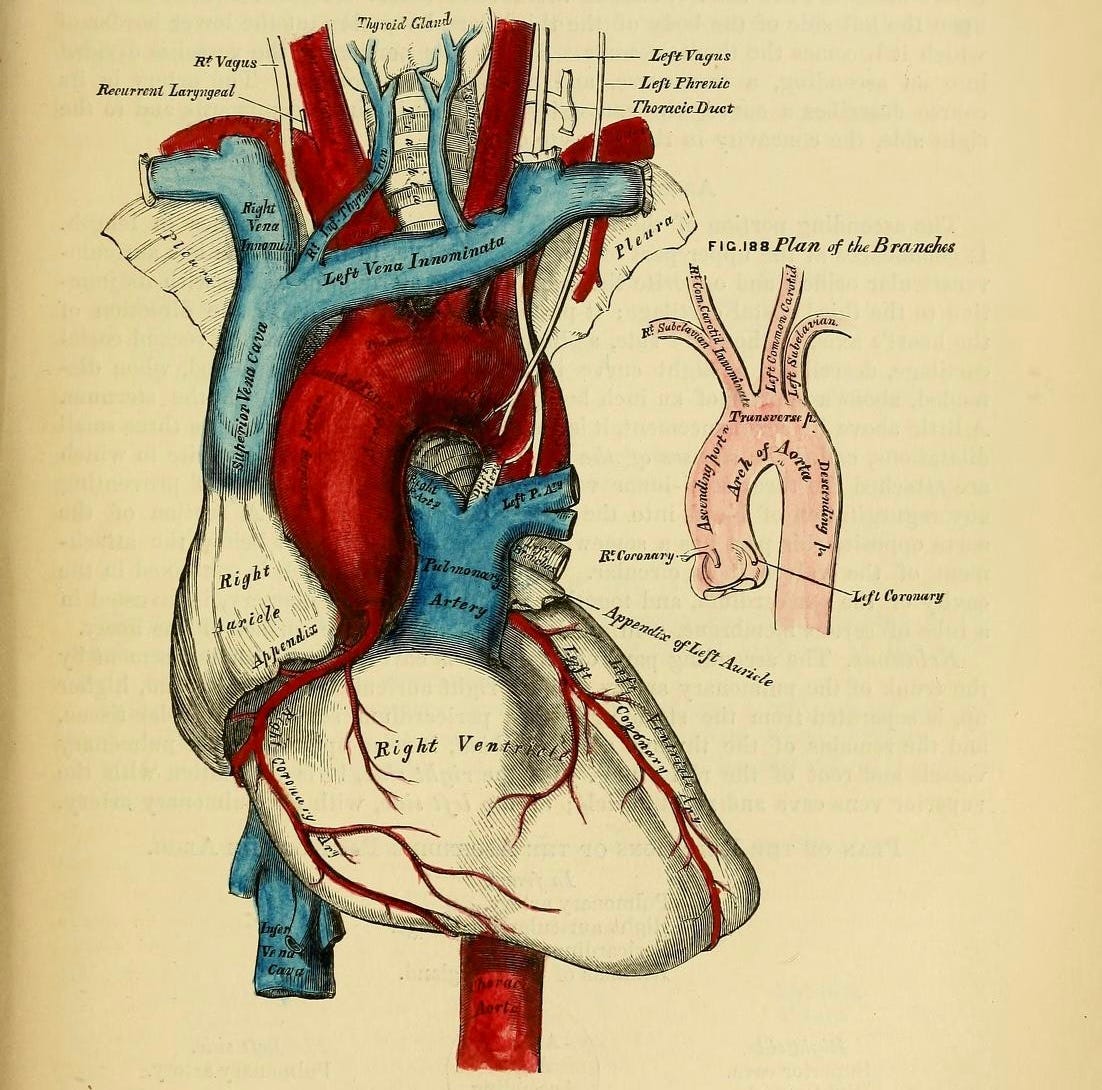

The Anatomy Act of 1832 ended the use of executed murderers for dissection, a practice that had been in place for eighty years and contributed to anatomical study’s murky reputation. The Act also – for the most part – ended bodysnatching, wherein the ‘resurrection-men’ would exhume freshly-buried bodies under cover of darkness and sell them to the anatomy schools for significant sums.

Cadavers for dissection by medical students, however, had to come from somewhere. The Act allowed anyone with guardianship of a dead body to offer it for study, provided the deceased had not made it clear that this was against their wishes. The hospital receiving the cadaver had to pay for its eventual funeral – a possible incentive for some poor families to take up the offer. In practice, however, relatives would usually do everything they could to afford their loved one’s burial. It was more common for bodies to come from public institutions such as workhouses, where people frequently died with no known family or friends. In these cases, the workhouse master was officially the one in possession of the body and able to make decisions about its fate.

This increased the availability of cadavers but, in a large city like London, bodies could still be in short supply. In 1857, a scandal showed that although the old resurrectionists might have hung up their shovels and dark lanterns, there were still people prepared to profit from the illicit sale of corpses.

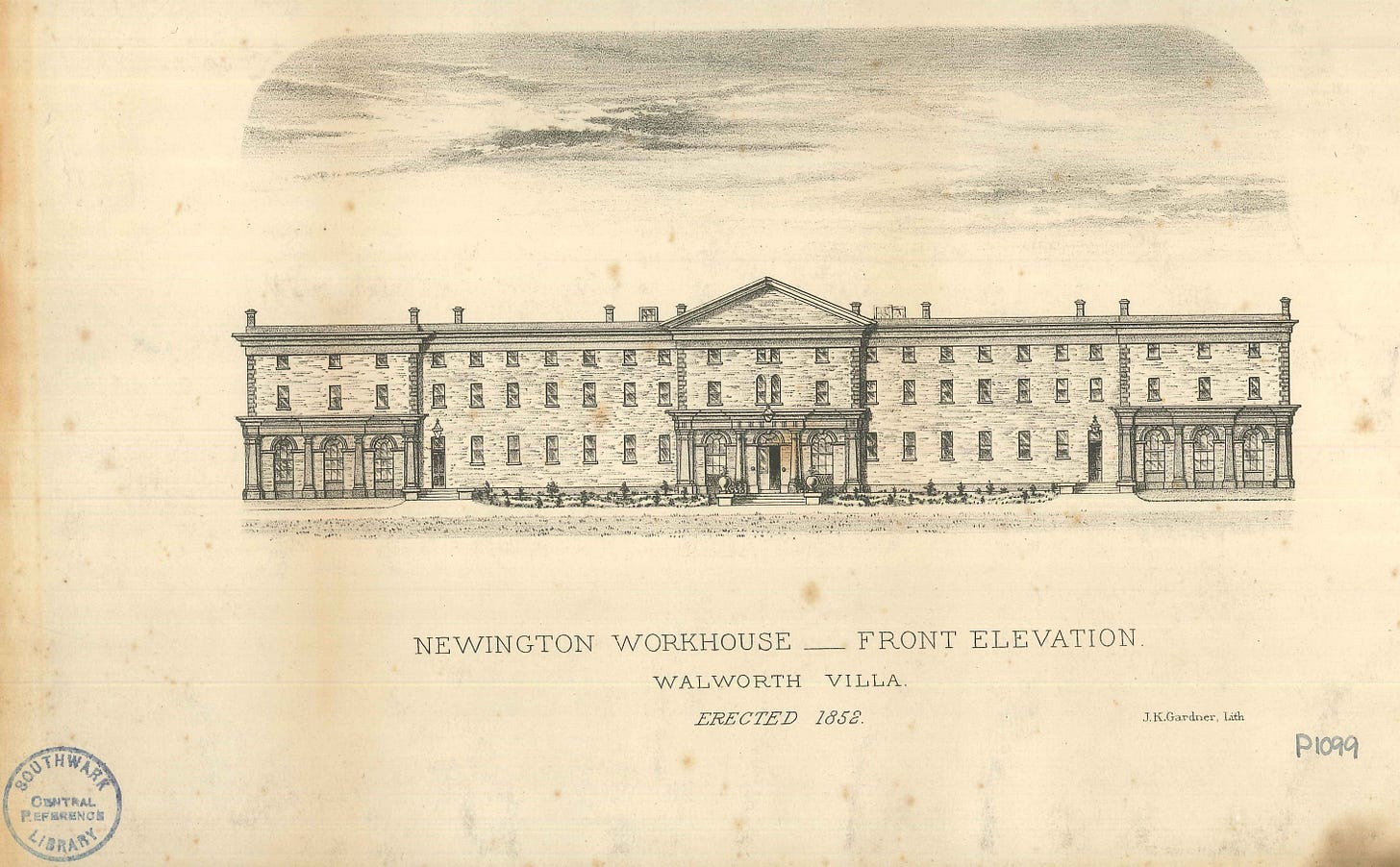

Outrage erupted in December 1857 around an exploitative and macabre system operated by Newington Workhouse in Walworth, south London. Alfred Feist, the institution’s master, appears to have carried on a money-making scheme established by the previous incumbent in cahoots with local undertaker, Robert Hogg.

The Newington Board of Guardians paid Hogg to do all the parish burials. When a workhouse inmate died and had relatives who couldn't afford a funeral, Hogg organised a simple service that the family could attend.

When someone without relatives died, Feist notified the Inspector of Anatomy, who authorised Guy's Hospital to take the body for dissection. About six weeks later, when the hospital had finished with the remains, Robert Hogg was contracted to sort out the burial. He got paid a lot more by the hospital than he would for an ordinary parish funeral, so the more bodies that went for dissection and subsequently came back, the more he earned. By a bit of sleight of hand, Hogg and Feist maximised profits.

They allowed relatives to view the deceased on the day of the funeral, then would ask them to wait outside until it was time to follow the hearse. During this gap, the pair substituted a body who had already been dissected. The family would unwittingly attend the burial of a stranger’s ‘mangled remains’ while their own loved one was sent to the anatomy school at Guy’s.

Feist benefited from this because the hospital gave an annual gratuity to workhouse masters for doing the necessary admin, and a larger number of corpses meant more money. Robert Hogg not only got a good fee from the hospital for burying the dissected bodies, but he also charged those burials to the parish, thereby getting paid twice. All his pauper coffins were the same, so he could easily swap one for another without getting his hands dirty.

The full details emerged in 1858, when Alfred Feist was summoned to Bow Street Police Court for the deception. Robert Hogg was called as a witness, and because he was prepared to testify against Feist, he did not face any charges of his own. He portrayed his actions as being under Feist’s orders, and rather absurdly claimed that Feist told him the people following the hearses were not the deceased’s family ‘but merely came there for a ride.’1

A woman in her seventies, Mary Whitehead, had lived at the workhouse for two years before dying from chronic bronchitis in January 1857. Her daughter Louisa Mixer visited her frequently and last saw her the day before her death. She did not have the money for a funeral, so Hogg agreed to arrange it at parish expense. Mrs Mixer was allowed to see her mother’s body in the ‘dead house’ and then had to wait outside until the coffin was carried to a hearse. She followed the hearse and attended her mother’s funeral – or so she thought.

Meanwhile, Mary Whitehead’s body was on the way to Guy’s Hospital with all the correct paperwork. The Inspector of Anatomy had granted a warrant for her dissection on being told that she had no family to claim her.

At the Old Bailey on 22 February 1858, more witnesses came forward with evidence that their loved ones had been treated in a similar manner. Charles Greenwood, Phoebe Clarke and George Thompson had all died in the workhouse and been sent for dissection while their families were at their sham funerals. They were just a few of the 64 counts brought against Feist.

Feist was found guilty, and the jury made it clear that they recognised Hogg’s role in the scheme, even though he had been granted immunity from prosecution:

The jury expressed their regret that any offer should have been made to the witness Hogg, which had prevented him standing by the side of the defendant.2

The Court for the Consideration of Crown Cases Reserved later quashed Feist’s conviction because lying to a deceased person’s family was not technically prohibited under the Anatomy Act. The relatives had also not specifically stated that they did not want the deceased dissected – presumably this did not cross their minds because they thought they were going to a normal funeral.

These families were exploited and treated inhumanely in their grief, and yet their social and economic status made them powerless to fight back.