Mr Grimstone's Egyptian mummy pea

A maker of herbal snuff branched out into resurrecting an ancient plant

Welcome to The Quack Doctor, a weekly publication that unearths stories from the history of medicine and related themes.

It’s free to subscribe, but if you would like to make a one-off contribution to the coffee supplies that keep me going, please go to my Ko-fi page here. Thank you!

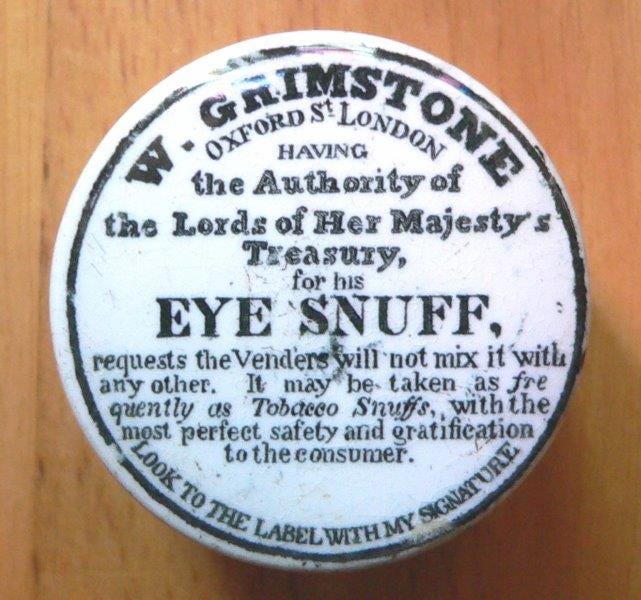

In a Highgate garden known as the Herbary, there grew plants destined to invigorate nostrils all over the world. Savory, rosemary and lavender scented the air, while orris-root thrived under the carefully cultivated soil. Dried, powdered and mixed with salt, they would become Grimstone's Eye Snuff and, according to advertisements, would cure cataracts, eradicate the need for spectacles and render the breath impervious to contagion. Sharing these plants’ London home were the ingredients for Grimstone's Aromatic Regenerator, whose herbal powers would introduce hair to the baldest pate and simultaneously ensure freedom from headaches and faintness.

In 1844, however, the Herbary became the site of an even more miraculous regeneration – the supposed resurrection of a plant that had lain dormant for millennia in an Ancient Egyptian tomb.

William Grimstone, the Herbary’s owner, said that during the 1830s, the 'mummy pea' had travelled to the British Museum in a sealed vase under the custodianship of the Egyptologist Sir John Gardner Wilkinson.

There, it was examined by Thomas J Pettigrew, a surgeon and antiquarian whose 1834 book, History of Egyptian Mummies, had contributed to the prevailing fascination with all things Egyptian. He gained renown for his mummy-unrolling lectures, and became known as ‘Mummy Pettigrew.’ Pettigrew had attempted to open the vase and, 'unfortunately broke it into several pieces.'

‘The interior,’ reported the London German Gazette, looking back on these events from 1849, ‘contained a mass of vegetable dust, with a few grains of wheat and vetches; he was, however, amply indemnified for the destruction of the vase by discovering in this dust a certain number of peas, entirely shrivelled.’1

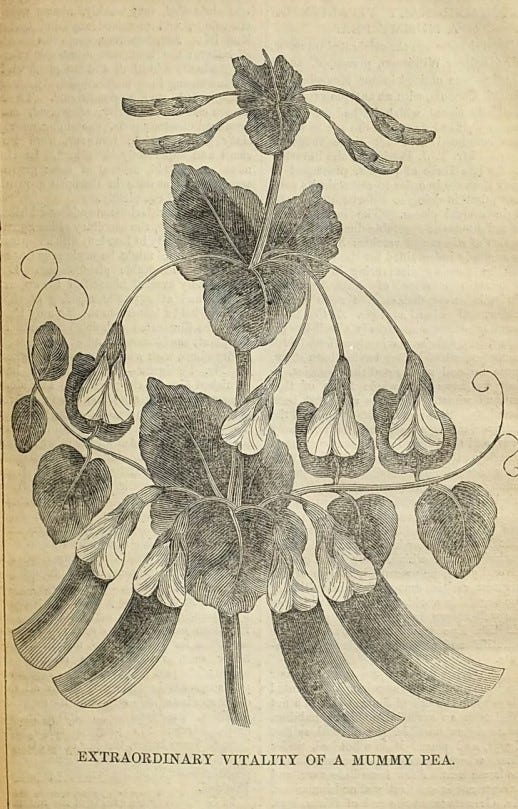

Early attempts at germination failed, and it was only after Pettigrew had passed the last three peas on to Grimstone that the latter's gardening expertise enabled one of them to sprout. Grimstone planted the peas on 4 June 1844 in a pot containing ‘an artificial mould resembling, as nearly as possible, the alluvial soil of Egypt’, and nurtured them in a warm environment under glass. After thirty days, a seedling peeped into the light; a pale and weedy specimen, it didn’t look very promising, but an increase in heat and more air got it thriving.

The plant produced nineteen pods with sixty small, imperfectly developed grains, and the next year these led to a successful crop grown outdoors. After that, Grimstone was well away, promoting ‘Grimstone's Egyptian Pea’ as a high-yielding variety with added Pharaonic mystery.

The story was not all that unusual; 'mummy wheat' was already a thing.2 A famous example that germinated in 1840 in the garden of the poet Martin Farquhar Tupper appears to have come from the same vase as the peas, and the idea of reviving ancient life has persisted ever since - most recently in reports that woolly mammoths could once more roam the tundra.

In 1849, the mummy pea attracted wider attention when Dr William Plate of the Syro-Egyptian Society gave a lecture on it at Grimstone’s request. By August of that year, however, newspapers were reporting that the phenomenon wasn't all it was cracked up to be:

...it is a slow grower—extremely shy in bearing—has a common field-pea appearance—nothing to boast of in quality, and has been pronounced by all who have been duped into its purchase as being nothing more or less than a piece of mere humbug!3

The Journal of Horticulture was also sceptical and grew a sample of mummy peas alongside a modern variety, the Dwarf Branching Marrow Pea:

With every advantage of comparison thus afforded by the proximity of the plants, no difference could be observed between Grimstone's Egyptian Pea and the Dwarf Branching Marrow. The growth of the plants, their foliage, flowers, pods, and seeds exhibited precisely the same characteristics.4

The likelihood was either that Grimstone and his gardeners were deliberately faking, or that the seed samples had accidentally been mixed up with newer peas.

In 1850, William Grimstone was left insolvent with debts of £6,000 owing to the numerous prosecutions brought against him for selling Eye Snuff without paying tobacco duty, and retailers’ demands that he reimburse them when they got fined too. The prosecutions were unfair bearing in mind the product did not contain tobacco.

Dr A L Wigan, in his A New View of Insanity (1844) claimed (approvingly) that Grimstone’s snuff mainly comprised black pepper. He didn’t give any evidence for this, however, and perhaps more reliable is the later analysis published by Dr Hassall of the Lancet Analytical Sanitary Commission, which suggested that it comprised herbs including orris-root, savory, rosemary and lavender, plus a fairly high proportion of salt.5

In the end Grimstone was discharged from the debtor’s court, kept possession of the Herbary and carried on selling Egyptian Peas, Eye Snuff, Aromatic Regenerator and other products for many more years. A ‘Mummy white’ pea variety remains available for present-day gardeners to cultivate their own link with the Ancient Egyptian tombs.

‘Extraordinary Vitality of a Mummy Pea’, reproduced from The London German Gazette in The Magazine of Science, vol XII, 1850.

‘Resuscitated mummy wheat’, The Morning Post, 15 August 1843.

‘The Mummy Pea,’ The Morning Post, 6 August 1849.

Journal of the Horticultural Society of London, vol IV, 1849.

Arthur Hill Hassall, MD, Food and its Adulterations, 1855.