Perkins' Tractors: a fashionable remedy put to the test

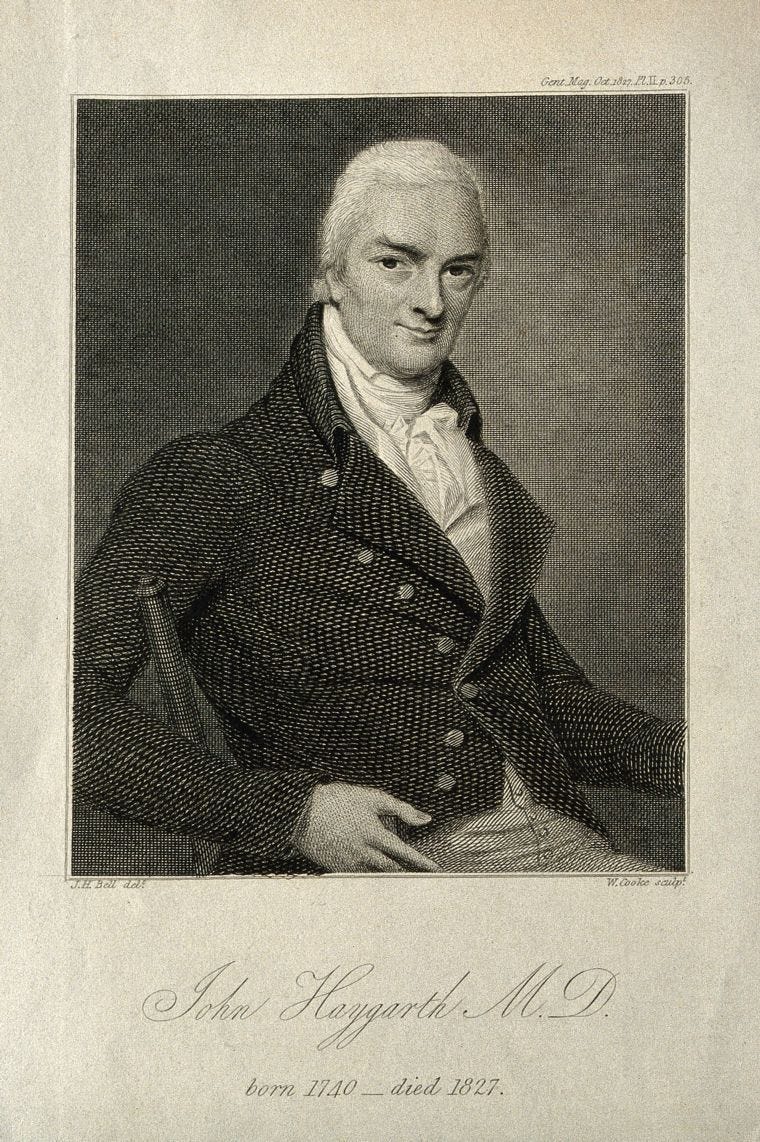

A medical device called Perkins' Metallic Tractors was investigated by Dr John Haygarth in 18th-century Bath.

Late eighteenth-century Bath was a magnet for people of fashion. Assemblies, coffee houses, theatre and dance; sulphuric health-giving waters and Pump Rooms gossip – it was the perfect hothouse for the latest fad. At the close of the century, an American invention called Perkins' Metallic Tractors became the talk of the town, and is now remembered as the subject of an early clinical trial demonstrating pain-relieving placebo responses.

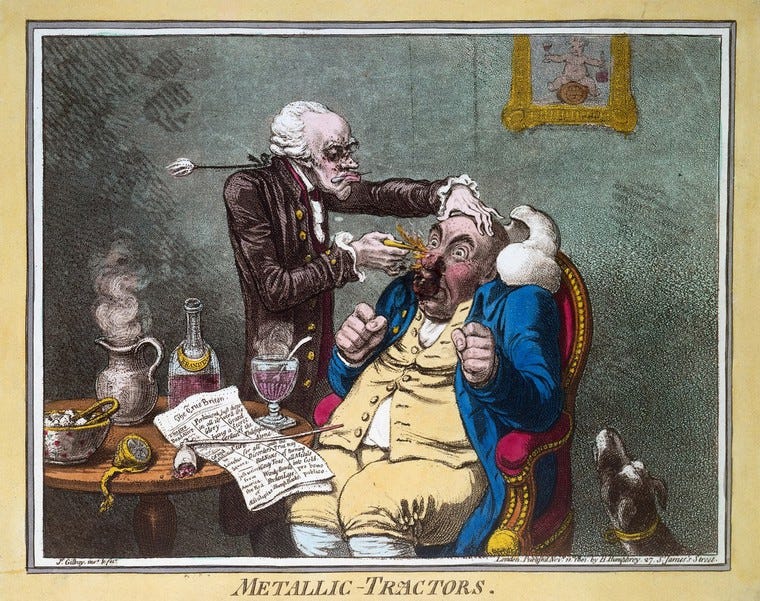

The Tractors originated with Connecticut physician Elisha Perkins (1741-1799), who patented them in 1796. These tapered metal prongs drew on the ideas of the Italian physician Luigi Galvani, who postulated that the body contained a fluid analogous to electricity. Supporters of 'Perkinean Electricity' believed this fluid could bunch up in areas of the body, causing pain. By drawing the Tractors over the skin, one could attract the fluid away from the painful area and bring relief.

Benjamin Douglas Perkins, son of Elisha, took the Tractors to England in the spring of 1798. He settled at 18 Leicester Square, London, and marketed them for five guineas – a sum that he described as ‘but a very trifling consideration’ given their usefulness.1 Musculoskeletal disorders such as rheumatism were the main targets, but promotional material also recommended them for eye inflammation, boils, epilepsy and numerous other complaints. They were not, however, presented as a cure-all – they wouldn't reach the internal organs, and if you had venereal disease or a hangover you were out of luck.2

Perkins' associate Charles Cunningham Langworthy, a surgeon, launched the Tractors in Bath, where they became the new big thing. Bath was also home to Dr John Haygarth (1740-1827), who had just retired there after a distinguished career as a physician and public health campaigner in Chester. I first encountered Haygarth when studying his work on isolation wards for smallpox, and his promotion of inoculation.

Haygarth was sceptical about the Tractors but not closed-minded – he was prepared to accept that they might work, and just needed some decent evidence. He wrote to his friend William Falconer, physician at Bath Infirmary, proposing an impartial test. The experiments would prove to be an important step in the development of clinical trials.

Haygarth and Falconer constructed wooden Tractors, painted to resemble the real thing. They then conducted a single-blind trial where the doctor performing the procedure knew the devices were fake, but the patients didn't.

The experiments started at Bath Infirmary on 7 January 1799, where five patients with chronic rheumatism underwent treatment with the wooden Tractors. Three felt a significant improvement and one gained some relief. The fifth, whose condition was not painful to start with, reported no change.

The following day, Haygarth and Falconer used real Perkins' Tractors, and the patients had a similar response. Haygarth concluded that this showed 'what powerful Influence upon diseases is produced by mere imagination.'3

The word 'placebo' (literally 'I shall please') had begun circulating in a medical context in the decades before Haygarth's experiments. In 1772, William Cullen used it to describe a medicine given to encourage the patient when there was little hope of curative effects. Haygarth himself did not use the term, but his experiments did show what we would now recognise as placebo responses – i.e. those resulting from something other than a physiological response to the treatment.

'The placebo effect', however, was not (and still isn't), a single thing. Many factors can combine to change someone's perception of their pain. Belief in the treatment could cause physiological changes such as the production of endorphins; then there's the patient's desire to get better, their wish to leave the hospital, their faith in the stories of wonderful cures, their personal like or dislike of the doctor, and so on. As a single-blind trial, Haygarth's experiments probably included some reporting bias on the part of the experimenters too.

Haygarth published his results in 1800 in Of the imagination, as a cause and as a cure of disorders of the body. He concluded that the Metallic Tractors could not be operating on the principle of Galvanic electricity. More importantly, he pointed out that if the trials hadn't included the fictitious Tractors, the real ones would have appeared impressive – he was illustrating the importance of comparing new treatments against a control.

Benjamin Perkins published a rebuttal of Haygarth's methods and glossed over the fact that the experiments had made this comparison. He accused Haygarth simply of creating fraudulent Tractors in order to trick people, and to have ‘only drawn out from the patient the assent of relief’ through imposition and ‘extreme illiberality’ that ‘could not but awaken the resentment of every friend to science, to humanity, and to truth.’4

Although Haygarth's work gained a lot of publicity, Metallic Tractors remained on the market, taking a few years to decline in popularity. In 1803, Perkins’ supporters set up the charitable Perkinean Institution in Frith Street, Soho, to provide treatment to the poor. Even after Benjamin Perkins' death in 1810, some people retained faith in the Tractors – as late as 1828 a gentleman called Mr J V Hall of Maidstone claimed to haved cure tetanus with them, and to have five sets available for the community to use free of charge.5 By then, however, the Tractors were mostly seen as an outdated fad.

Although Perkins portrayed Haygarth’s experiments as a narrow-minded attempt to discredit the Tractors, that wasn't really Haygarth's point. He wanted to test whether or not they worked and was prepared to accept the evidence either way. Although the experiments were not as rigorous as a double-blind trial would have been, they formed a significant early step in the ongoing process of making clinical research as objective as possible.

HistMed Highlights

PATENT MEDICINE ARTWORK: 🎨🫙The Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors is hosting an online seminar about the advertising art of the popular 19th-century medicine, Warner’s Safe Cure. 12 December 2023, 7pm CT, Free – sign up for Zoom invitation.

HEALTH SERVICE HISTORY: 📖 Emma Snow’s new book, The First NHS: How John Tomley’s work led to modern healthcare highlights the life and work of a forgotten campaigner, and the founding of the WNMA to eradicate tuberculosis in Wales. Out 28 November 2023 from Pen and Sword.

FOUNDLING HOSPITAL: 🧸In 1763, a satellite branch of London’s Foundling Hospital was opened at Chester to receive abandoned children from the capital. In this talk at the Wheeler Building, Chester University, Dr Anthony Annakin-Smith gives the moving history of this little-known institution. 6 December 2023, 4pm GMT. Free but book by email.

Perkins, B., The influence of metallic tractors on the human body, 2nd ed. (1799).

Perkins, B., Directions for performing the metallic operation with Perkins's patent tractors, (c. 1798).

Haygarth, J., Of the imagination, as a cause and as a cure of disorders of the body, (1800).

Perkins, B., The efficacy of Perkins's patent metallic tractors, in topical diseases on the human body, and animals, (1800)

The Morning Herald (London), 15 November 1828.